[BACK]

[Blueprint] [NEXT]

=============

From Old Church Lore by William Andrews; William Andrews & Co., The Hull Press; London, 1891; pp. 65-79.

[65]

[65]

Charter Horns

N the Cathedrals of York and Carlisle are preserved interesting charter horns. The horn, in bygone times, often played an important part when land was granted. In some instances ancient drinking horns are the only charters proving the ownership of extensive possessions. The blowing of the horn has formed, and still forms, the prelude of many quaint customs for maintaining certain manorial and other rights. Some of the details of the old services of manors are extremely romantic, and supply not a few strange chapters in local and national history. Romance, in some of the records, takes the place of dry matter-of-fact statements, and adds not a little to the pleasure of the study of past ages.

N the Cathedrals of York and Carlisle are preserved interesting charter horns. The horn, in bygone times, often played an important part when land was granted. In some instances ancient drinking horns are the only charters proving the ownership of extensive possessions. The blowing of the horn has formed, and still forms, the prelude of many quaint customs for maintaining certain manorial and other rights. Some of the details of the old services of manors are extremely romantic, and supply not a few strange chapters in local and national history. Romance, in some of the records, takes the place of dry matter-of-fact statements, and adds not a little to the pleasure of the study of past ages.

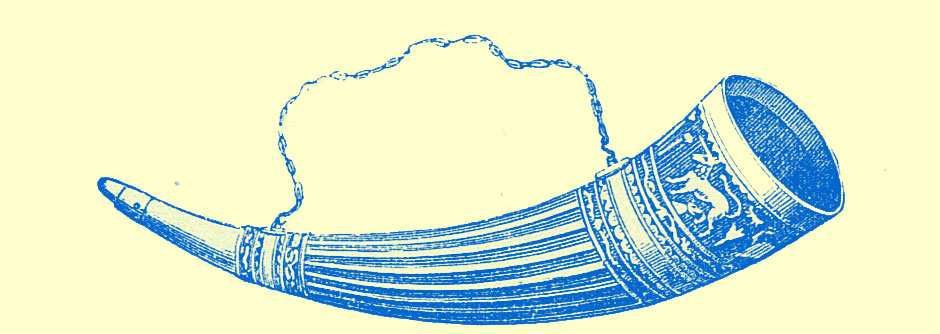

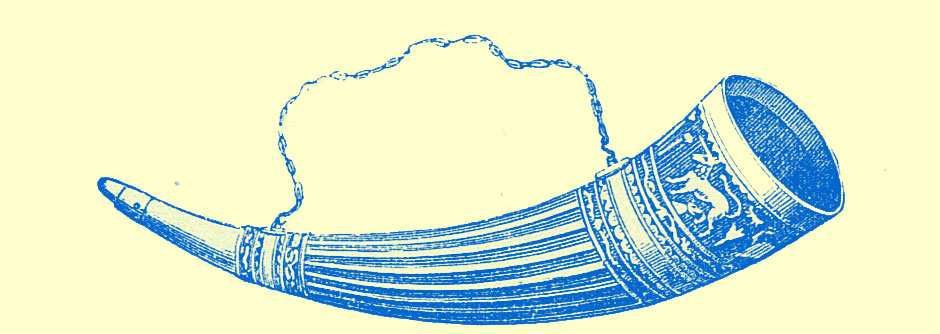

The important Horn of Ulphus is preserved in the treasure room of York Minster, and, apart

66

from its rich historical associations, it is an object of great beauty. It is made from a portion of a large tusk of an elephant. Were this horn totally without a history or a tradition connected with it, its elaborate and peculiar character of ornamentation would render it an object of interest and value. It has two bands, one near the thinner end and the other at about a fifth part of the length from the thicker end.

THE HORN OF ULPHUS.

The space between the latter band and the end is adorned with sculptures in low relief, which express much that in European mediæval art did not appear for several hundreds of years later than the date of the horn, and which, it may fairly be supposed, are of Asiatic origin. The band of carvings is about four inches in width, and there are four chief figures. One appears to be an unicorn performing the act that, in the credulous natural history of long ago, it was so apt to indulge — namely, piercing a tree

67

with its one horn, and so fixing itself and being at the hunter’s mercy. The unicorn is the symbol of chastity. At the other side of the tree is a lion killing and devouring a deer. Next, facing another tree with palmated leaves and grape-like fruit, is a gryphon, a creature having the body of a lion and the head and wings of an eagle. At the other side of this tree, and facing the gryphon, is a similar monster, which has, however, the head of a dog or wolf. The lion’s tail is foliated, while those of the winged beasts end in ludicrous dogs’ or wolves’ heads. Three wolves’ heads, collared, rise from the ground-line, and a wolf runs in the upper part, and it is not unlikely that Ulphus (or Ulf, equal to our word wolf) is so hinted at. The form of the animals, especially whose which have wings, are Assyrian in feeling and treatment, while the treatment of the trees still further adds to the opinion that the horn is not a specimen of European carving.

Mr. Robert Davies, F.S.A., Town-Clerk of York, who wrote a monograph on this celebrated relic, from which a few of our particulars are drawn, conjectures that the horn would be brought to the Baltic shores by Arabic merchants; if so, it will be then more feasible to

68

suppose that the carving would be executed previous to its being brought for sale. Having so far considered the form of the horn, let us next look a little into its history. The tradition, accepted from time immemorial, is simply this — that, a considerable period before the Conquest, the horn was given to the see of York by a Dane who had settled in England, as a symbol of endowment of the wide lands which he conferred upon the episcopate. This tradition comes down to the present day through various channels. First is a poem in Latin (among the Cotton MSS.), describing the different gifts to York, up to about the twelfth century. In this, Ulf is described as an eminent Yorkshire earl and ruler, his gifts to the church are mentioned, and their confirmation by Edward the Confessor, the horn is noted to be the sign of endowment, and its great beauty enlarged upon. In one particular, the description differs from one that might be written at the present day, inasmuch that, whereas the horn is stated in the poem to be white, its hue now is brown. In Holland’s “Britannia,” the tradition is given as historically true, and in the following words: “Then it was, also, that princes bestowed many great livings

69

and lands upon the church of York, especially Ulphus, the son of Torald (I note so much out of an old book, that there may plainly appear a custom of our ancestors in endowing churches with livings). This Ulphus, aforesaid, ruled the west part of Deira, and by reason of the debate that was like to arise between his sons, the younger and the elder, about their lordships and their seigniories after his death, forthwith he made them all alike. For, without delay, he went to York, took the horn with him out of which he was wont to drink, filled it with wine, and, before the altar f God, blessed Saint Peter, prince of the Apostles, kneeling upon his knees, he drank, and thereby enfeoffed them [the church] in all his lands and revenues. Which horn was there kept, as a monument (as I have heard) until our fathers’ days.”

In Domesday Book is mentioned an English thane named Ulf, who, in the reign of Edward the Confessor, had held large possessions in Northumbria, which, at the time of the Domesday Survey, had become the property of the see of York. It is further stated, that large territories which were held by the Archbishop of York, at the time of the Conquest, had also been owned by this same

70

Ulf. In Kirkby’s “Inquest” (temp. Edward I.), these lands are again noted to be the gift of Ulf. Thus far, the tradition is corroborated by history, but the statement that Ulf’s sons were disinherited is incorrect, for Ulf had a large extent of property left after making his munificent gift to the Church, which his sons in due time inherited. These two sons, Archil and Norman, are included among the King’s thanes in Domesday Book. There was also another Ulf, who lived in the time of the King Canute, dying in 1036, but, though confounded with the Ulphus of our story, he was not the same, and had nothing to do with the charter horn of York.

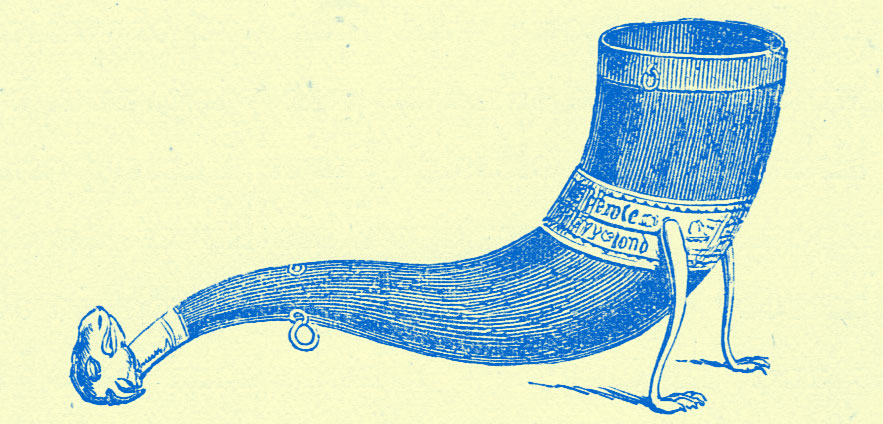

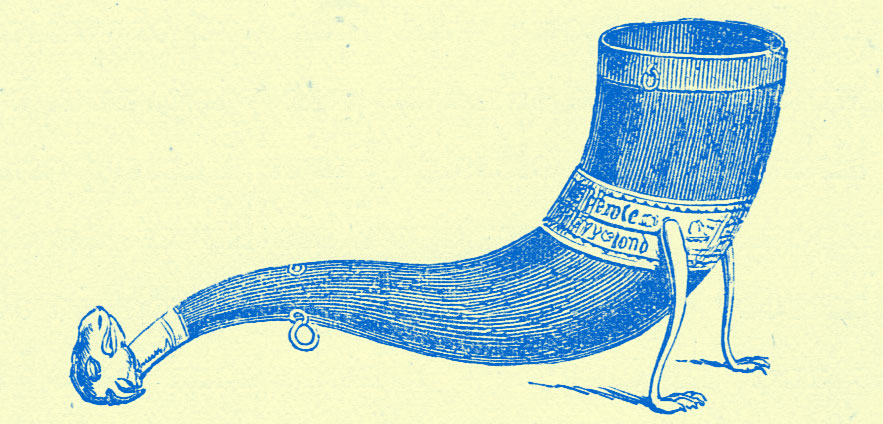

THE PUSEY HORN.

The Pusey Horn, preserved at Pusey House, near Farringdon, has a curious traditional history, carrying us back to the days of the warlike Canute, and his struggles with the Saxons. It is related, that, on one occasion, the king’s soldiers

71

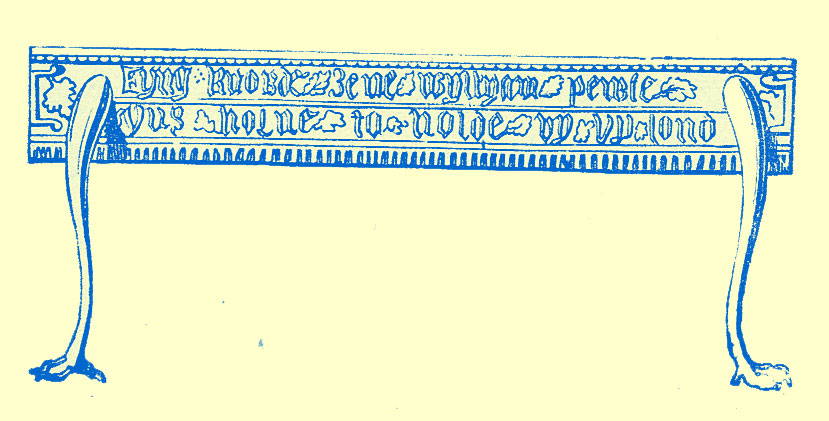

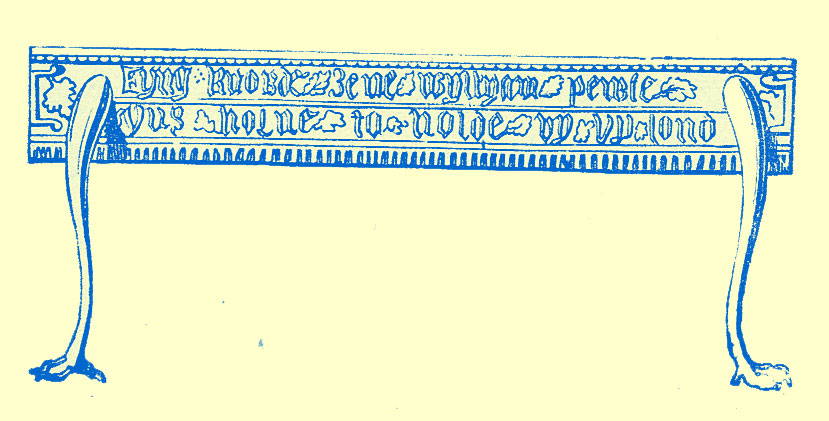

and the Saxons were encamped near each other, in the neighbourhood of Pusey. An ancestor of the Pusey family, serving as an officer under the king, discovered an ambuscade, formed by the Saxons, to intercept the king’s army. He gave Canute a timely intimation of their intentions, and thus enabled him to foil their plans. For this important information, Canute gave to his informant and his heirs the manor of Pusey, and as a ratification of the grant, a horn was presented. It is the horn of an ox, measuring two feet and half-an-inch in length, and at the larger end is a foot in circumference. The colour of it is dark brown. Round the middle is a ring of silver-gilt, and the horn is supported on two hound’s feet. The small end has a screw stopper, also of silver-gilt, in the form of a hound’s head. It forms with the stopper a drinking horn, and without it a hunting horn. The silver ring bears the following inscription:

72

Hickes, writing about 1685, states: “Both the horn and manor were in his time possessed by Charles Pusey, who had recovered them in Chancery, before Lord Chancellor Jefferies; the horn itself being produced in court, and with universal admiration received, admitted, and proved to be the identical horn by which, as by charter, Canute had conveyed the manor of Pusey about seven hundred years before.” On the 25th of October, 1849, at a festival at Wantage, Berkshire, to celebrate the anniversary of the birthday of King Alfred, a dinner was held, and amongst the guests were Mr. Pusey, M.P>, John Britton, the antiquary, and other notable men. It is reported that, “during the proceedings, a pleasureable interest was excited by the production of the extraordinary piece of antiquity, the Pusey Horn, presented by King Canute to the ancestor of Mr. Pusey, and forming the original tenure of the Pusey property, and inalienable from it.”

According to a popular legend, Edward the Confessor presented to a huntsman named Nigel, and his heirs, a hide of land and a wood called Hulewood, and the rangership of the royal forest of Bernwood, Buckinghamshire, as a reward for

73

his courage in slaying a large wild boar which infested the place. The land was called Derehyde, and on it he built a house, naming it Borestalle, in memory of the slain animal. The grant was accompanied with a horn, which is preserved by the lords of Borestalle, and is known as Nigel’s horn. It is described as “being of a dark-brown colour, variegated and veined like tortoise-shell, and fitted with straps of leather to hang about the neck. It is tipped at each end with silver-gilt, and mounted with a plate of brass, having sculptured thereon the figure of a horn, and also several plates of silver-gilt fleurs-de-lis, and an old brass seal ring.” In addition to the horn, is also preserved, an old folio vellum volume, containing transcripts of charters and evidences relating to the estate. It contains, we read, a rude drawing of the size of Borstall House and Manor, and under is the rude figure of a man presenting, on his knees, to the king, the head of a boar, on the point of a sword, and the king returning to him a coat-of-arms, arg. a fesse, gu. two crescents, and a horn, verde. The armorial bearings belong to a much later period than the reign of Edward the Confessor.

Before the Rhyne Toll was collected in Buckinghamshire,

74

a horn was blown with not a little ceremony. The right of gathering the toll originated as a reward for a heroic deed performed in the days when the wild boar roamed the forests of England, much to the terror of the people. According to tradition, a ferocious boar had its lair in the ancient forest of Rookwoode. It kept the inhabitants of the district in constant fear of their lives, and prevented strangers visiting them. A valiant knight, the Lord of Chetwode, resolved to rid the country of the monster, or die in the attempt. Says an old ballad:

“Then he blowed a blast full north, south, east, and west —

Wind well thy horn, good hunter;

And the wild boar then heard him full in his den,

As he was a jovial hunter.

Then he made the best of his speed unto him —

Wind well thy horn, good hunter;

Swift flew the boar, with his tusks smeared with gore,

To Sir Ryalas, the jovial hunter.

Then the wild boar, being so stout and so strong —

Wind well thy horn, good hunter;

Thrashed down the trees as he ramped him along

To Sir Ryalas, the jovial hunter.

Then they fought four hours on a long summer day —

Wind well thy horn, good hunter;

Till the wild boar would fain have got him away

From Sir Ryalas, the jovial hunter.

75

Then Sir Ryalas he drawed his broad sword with might —

Wind well thy horn, good hunter;

And he fairly cut the boar’s head off quite,

For he was a jovial hunter.”

The countryside rang with the knight’s praise, and the king heard the welcome news. The sovereign, as a reward for his services, made “the jovial hunter,” we are told, “the knight tenant in capite, and constituted his manor paramount of all the manors within the limits and extent of the royal forest of Rookwoode.” The privilege of levying toll on all cattle passing through nine townships was granted to him and his heirs for ever. It was known as the Rhyne Toll, and commenced at midnight on October 29th, and ended at midnight on November 7th annually. Before the commencement of the collection of the toll, a horn was blown as we have previously stated, with some ceremony. The toll was collected until 1868, when it was given up by Sir George Chetwode, the lord of the manor.

In the Chapter House, at Carlisle, is preserved an interesting relic known as the “Horns of the Altar.” Mr. Frank Buckland inspected it in 1879, and expressed his astonishment at finding it to be a walrus’s skull, without the lower jaw, with tusks about eighteen inches long. The skull

76

itself was marked out with faded colours, so as to somewhat resemble a human skull. Canon Prescott supplied Mr. Buckland with some information about this curious charter horn. He said: “In the year 1290, a claim was made by the King, Edward I., and by others, to the tithes on certain lands lately brought under cultivation in the forest of Inglewood. The Prior of Carlisle appeared on behalf of his convent, and urged their right to the property on the ground that the tithes had been granted to them by a former king, who had enfeoffed them by a certain ivory horn (quoddam cornu eburneum), which he gave to the Church of Carlisle, and which they possessed at that time. The Cathedral of Carlisle has had in its possession for a great number of years two fine walrus tusks, with a portion of the skull. They appear in ancient inventories of goods of the cathedral as ‘one horn of the altar, in two parts,’ or ‘two horns of the altar’ (1674), together with other articles of the altar furniture. But antiquaries come to the conclusion that these were identical with the ‘ivory horn’ referred to above. Communications were made to the Society of Antiquaries (see Archæologia, Vol. III.) and they were called the ‘Carlisle Charter

77

Horns.’ Such charter horns were not uncommon in ancient days. Bishop Lyttleton (1768), in a paper read before the society, said the ‘horns’ were so called improperly, being ‘certainly the teeth of some very large sea fish.’ It is probable that they were presented to the church as an offering, perhaps by some traveller, and used as an ornament to the altar. Such ornaments were frequent, both at the smaller altars and in the churches.”

Mr. Buckland, adverting to the foregoing, says: ‘I cannot quite understand how a walrus’s skull and teeth came to be considered so valuable as to be promoted to the dignity of a charter horn of a great cathedral like Carlisle. I am afraid Bishop Lyttleton, 1768, was not a naturalist, or he would never have called the tusks of a walrus ‘the teeth of some very large fish.’”

Hungerford, a pretty little town at the extreme west end of the royal county of Berks, has its ancient charter horn, and linked to it are some curious customs. A contributor to a local journal for 1876, states that “the town of Hungerford, Berkshire, enjoys some rare privileges and maintains some quaint customs. The inhabitants have the right of pasturage and of shooting over a

78

large tract of downs and marsh land bequeathed to them by John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, subject to the annual observance of certain customs at this period of the year. They have also the right of fishing for trout in the Kennet, which flows through the borough. Hockney-day and the usual customs have just been observed in their integrity. The old horn, by which the tenure is held. had been blown from the Town Hall, summoning the commoners to their rights, and the tything men, whose duties are unique, have ably fulfilled them. These gentlemen carry long poles, decorated with flowers and garlands, having to call at each house and exact the tribute of a coin from each male, and a kiss from each lady. The High Constable or Mayor, whose office combines the duties of the coroner, is chosen on this day.”

Blowing three blasts on a horn formed part of an old custom at Chingford, Essex. Blount, in his “Tenures of Land,” and the historians of the county, direct attention to the ceremony. The estate of Brindwood’s was held under the following conditions: Upon every alteration , the owner of the estate, with his wife, man servant, and maid servant, each single on a

79

horse, come to the parsonage, where the owner does his homage, and pays his relief in the manner following — he blows three blasts with his horn, carries a hawk on his fist, and his servant has a greyhound in a slip, both for the use of the rector for the day; he receives a chicken for his hawk, a peck of oats for his horse, and a loaf of bread for his greyhound. They all dine, after which the master blows three blasts with his horn, and they all depart. A correspondent to the Gentleman’s Magazine for 1790, gives particulars of this custom being kept up in the days of Queen Elizabeth.

At Bainbridge, the chief place of the forest of Wensleydale, Yorkshire, still lingers an old horn-blowing custom. An instrument known as the forest horn is blown on the green every night at ten o’clock from the first of September to Shrovetide. It is a very large one, and made from the horn of an ox. Its sound on the still night air may be heard for a considerable distance. In bygone ages, horns were blown to enable belated travellers to direct their course over the almost trackless roads to their destinations, and the welcome notes of the horn have saved many a lonely wayfarer from perishing in the snow.

=============

[BACK]

[Blueprint] [NEXT]

N the Cathedrals of York and Carlisle are preserved interesting charter horns. The horn, in bygone times, often played an important part when land was granted. In some instances ancient drinking horns are the only charters proving the ownership of extensive possessions. The blowing of the horn has formed, and still forms, the prelude of many quaint customs for maintaining certain manorial and other rights. Some of the details of the old services of manors are extremely romantic, and supply not a few strange chapters in local and national history. Romance, in some of the records, takes the place of dry matter-of-fact statements, and adds not a little to the pleasure of the study of past ages.

N the Cathedrals of York and Carlisle are preserved interesting charter horns. The horn, in bygone times, often played an important part when land was granted. In some instances ancient drinking horns are the only charters proving the ownership of extensive possessions. The blowing of the horn has formed, and still forms, the prelude of many quaint customs for maintaining certain manorial and other rights. Some of the details of the old services of manors are extremely romantic, and supply not a few strange chapters in local and national history. Romance, in some of the records, takes the place of dry matter-of-fact statements, and adds not a little to the pleasure of the study of past ages.