From The International Library of Masterpieces, Literature, Art, & Rare Manuscripts, Volume XXX, Editor-in-Chief: Harry Thurston Peck; The International Bibliophile Society, New York; 1901; pp. 11076-11093.

WHYTE-MELVILLE, GEORGE JOHN, an English novelist; born at Mount Melville, near St. Andrews, Scotland, 1821. He was fatally injured by a fall from his horse in the hunting-field, in the Vale of Aylesbury, and died December 5, 1878. He was educated at Eton. A captain in the Coldstream Guards, he retired from the army (1849), but served in the Turkish cavalry during the Crimean War. Among his works were “Captain Digby Grand” (1853); “The Gladiators” (1863); “Sarchedon” (1871); “Satanella” (1873); “Katerfelto” (1875); etc. He wrote also a volume of “Songs and Verses” (1869); and translated Horace’s “Odes.”

A HUNDRED thousand tongues, whispering and murmuring with Italian volubility, send up a busy hum like that of an enormous beehive into the sunny air. The Flavian Amphitheatre, Vespasian’s gigantic concession to the odious tastes of his people, has not yet been constructed; and Rome must crowd and jostle in the great Circus, if she would behold that slaughter of beasts, and those mortal combats of men, in which she now takes far more delight than in the innocent trials of speed and skill for which the enclosure was originally designed. That her luxurious citizens are dissatisfied even with this roomy edifice, is sufficiently obvious from the many complaints that accompany the struggling and pushing of those who are anxious to obtain a good place. To-day’s bill-of-fare is indeed tempting to the morbid appetites of high and low. A rhinoceros and tiger are to be pitted against each other; and it is hoped that, notwithstanding many recent failures in such combats, these two beasts may be savage enough to afford the desired sport. Several pairs of gladiators, at least, are to fight to the death, besides those on whom the populace may show mercy or from whom they may withhold it at will. In addition 11077 to all this, it has been whispered that one well-known patrician intends to exhibit his prowess on the deadly stage. Much curiosity is expressed, and many a wager has been already laid, on his name, his skill, the nature of his conflict, and the chances of his success. Though the Circus be large enough to contain the population of a thriving city, no wonder that it is to-day full to the very brim. As usual in such assemblages, the hours of waiting are lightened by eating and drinking, by jests, practical and otherwise, by remarks, complimentary, sarcastic, or derisive, on the several notabilities who enter at short intervals, and take their places with no small stir and assumption of importance. The nobility and distinguished characters of this dissolute age are better known than respected by their plebeian fellow-citizens.

There is, however, one exception. Though Valeria’s Liburnians lay themselves open to no small amount of insolence, by the emphatic manner in which they make way for their mistress, as she proceeds with her usual haughty bearing to her place near the patrician benches — an insolence of which some of the more pointed missiles do not spare the scornful beauty herself — it is no sooner observed that she is accompanied by her kinsman, Licinius, than a change comes over the demeanor even of those who feel themselves most aggrieved, by being elbowed out of their places, and pushed violently against their neighbors, while admiring glances and a respectful silence, denote the esteem in which the Roman general is held by high and low.

It wants a few minutes yet of noon. The southern sun, though his intensity is modified by canvas awnings stretched over the spectators wherever it is possible to afford them shade, lights and warms up every nook and cranny of the amphitheatre; gleams in the raven hair of the Campanian matron, and the black eyes of the astonished urchin in her arms; flashes off the golden bosses that stud the white garments on the equestrian benches; bleaches the level sweep of sand so soon to bear the prints of mortal struggle, and flooding the lofty throne where Cæsar sits in state, deepens the broad crimson hem that skirts his imperial garment, and sheds a death-like hue over the pale bloated face, which betrays even now no sign of interest, or animation, or delight.

Vitellius attends these brutal exhibitions with the same immobility that characterizes his demeanor in almost all the 11078 avocations of life. The same listlessness, the same weary vacancy of expression, pervades his countenance here, as in the senate or the council. His eye never glistens but at the appearance of a favorite dish; and the emperor of the world can only be said to live once in the twenty-four hours, when seated at the banquet.

Insensibility seems, however, in all ages to be an affectation of the higher classes; and here, while the plebeians wrangle, and laugh, and chatter, and gesticulate, the patricians are apparently bent on proving that amusement is for them a simple impossibility, and suffering or slaughter matters of the most profound indifference.

And on common occasions who so impassible, so cold, so unmoved by all that takes place around her, as the haughty Valeria? but to-day there is an unusual gleam in the gray eyes, a quiver of the lip, a fixed red spot on either cheek; adding new charms to her beauty, not lost upon the observers who surround her.

Quoth Damasippus to Oarses (for the congenial rogues stand, as usual, shoulder to shoulder): —

“I would not that the patron saw her now. I never knew her look so fair as this. Locusta must have left her the secret of her love philtres.”

“Oh, innocent!” replies the other. “Knowest thou not that the patron fights to-day? Seest thou her restless hands, and that fixed smile, like the mask of an old Greek player? She loves him; trust me, therefore, she has lost her power, were she subtle as Arachne. Dost not know the patron? To do him justice, he never prizes the stakes when he has won the game.”

And the two fall to discussing the dinner they have brought with them, and think they are perfectly familiar with the intricacies of a woman’s feelings.

Meantime Valeria seems to cling to Licinius as though there were some spell in her kinsman’s presence to calm that beating heart of which she is but now beginning to learn the wayward and indomitable nature.

For the twentieth time she asks: “Is he prepared at all points? Does he know every feint of the deadly game? Are his health and strength as perfect as training can make them? And oh, my kinsman! is he confident in himself? Does he feel sure that he will win?”

11079To which questions, Licinius, though wondering at the interest she betrays in such a matter, answers as before: —

“All that skill, and science, and Hippias can do, has been done. He has the advantage in strength, speed, and height. Above hall, he has the courage of his nation. As they get fiercer they get cooler, and they are never so formidable as when you deem them vanquished. I could not sit here if I thought he would be worsted.”

Then Valeria took comfort for a while, but soon she moved restlessly on her cushions. “How I wish they would begin!” said she; yet every moment of delay seemed at the same time to be a respite of priceless value, even while it added to the torture of suspense.

Many hearts were beating in that crowd with love, hope, fear, and anxiety; but perhaps none so wildly as those of two women, separated but by a few paces, and whose eyes women indefinable attraction seemed to draw irresistibly towards each other.

While Valeria, in common with many ladies of distinction, had encroached upon the space originally allotted to the vestal virgins, and established, by constant attendance in the amphitheatre, a prescriptive right to a cushioned seat for herself and her friends, women of lower rank were compelled to station themselves in an upper gallery allotted to them, or to mingle on sufferance with the crowd in the lower tier of places, where the presence of a male companion was indispensable for protection from annoyance, and even insult. Nevertheless, within speaking distance of the haughty Roman lady stood Mariamne, accompanied by Calchas, trembling with fear and excitement in every limb, yet turning her large dark eyes upon Valeria, with an expression of curiosity and interest that could only have been aroused by an instinctive consciousness of feelings common to both. The latter, too, seemed fascinated by the gaze of the Jewish maiden, now bending on her a haughty and inquiring glance, anon turning away with a gesture of affected disdain; but never unobservant, for many seconds together, of the dark pale beauty and her venerable companion.

When she was at last fairly wedged in amongst the crowd, Mariamne could hardly explain to herself how she came there. It had been with great difficulty that she persuaded Calchas to accompany her; and, indeed, nothing but his interest in Esca, and the hope that he might, even here, find some means of 11080 doing good, would have tempted the old man into such a scene. It was with many a burning blush and painful thrill that she confessed to herself, she must go mad with anxiety were she absent from the death-struggle to be waged by the man whom she now knew she loved so dearly; and it was with a wild defiant recklessness that she resolved if aught of evil should befall him to give herself up thenceforth to despair. She felt as if she was in a dream; the sea of faces, the jabber of tongues, the strange novelty of the spectacle, confused and wearied her; yet through it all Valeria’s eyes seemed to look down on her with an ominous boding of ill; and when, with an effort, she forced her senses back into self-consciousness, she felt so lonely, so frightened, and so unhappy, that she wished she had never come.

And now, with peal of trumpets and clash of cymbals, a burst of wild martial music rises above the hum and murmur of the seething crowd. Under a spacious archway, supported by marble pillars, wide folding-doors are flung open, and two by two, with stately step and slow, march in the gladiators, armed with the different weapons of their deadly trade. Four hundred men are they, in all the pride of perfect strength and symmetry, and high training, and practised skill. With head erect and haughty bearing, they defile once around the arena, as though to give the spectators an opportunity of closely scanning their appearance, and halt with military precision to range themselves in line under Cæsar’s throne. For a moment there is a pause and hush of expectation over the multitude, while the devoted champions stand motionless as statues in the full glow of noon; then bursting suddenly into action, they brandish their gleaming weapons over their heads, and higher, fuller, fiercer, rises the terrible chant that seems to combine the shout of triumph with the wail of suffering, and to bid a long and hopeless farewell to upper earth, even in the very recklessness and defiance of its despair: —

“Ave, Cæsar! Morituri te salutant!”

Then they wheel out once more, and range themselves on either side of the arena; all but a chosen band who occupy the central place of honor, and of whom every second man at least is doomed to die.

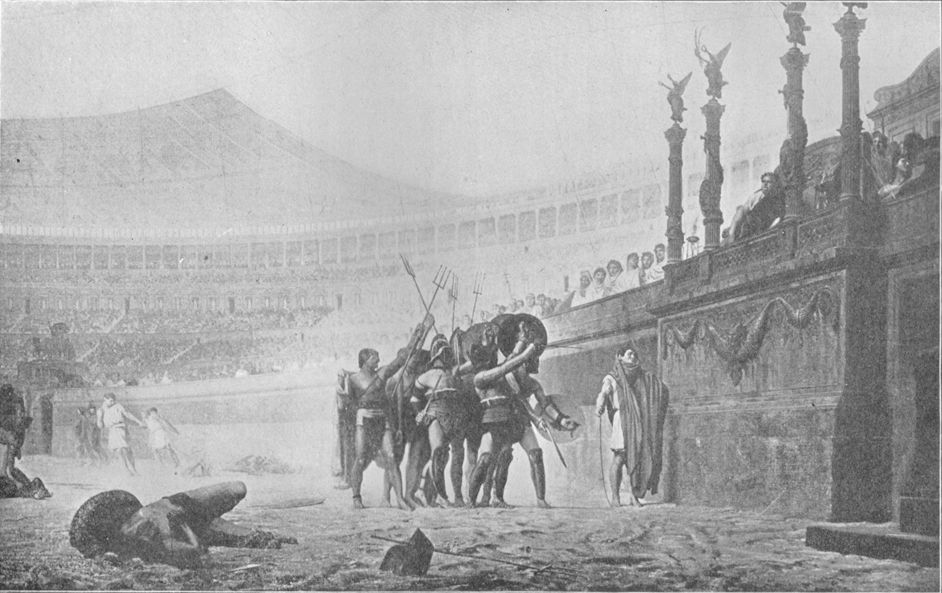

“Ave! Cæsar Imperator”

From a Painting by J. L. Gérôme

These are the picked pupils of Hippias; the quickest eyes and he readiest hands in “The Family;” therefore it is that they have been selected to fight by pairs to the death, and that 11081 it is understood no clemency will be extended to them from the populace.

With quickened breath and eager looks, Valeria and Mariamne scan their ranks in search of a well-known figure: both feel it to be a questionable relief that he is not there; but the Roman lady tears the edge of her mantle to the seam, and the Jewish girl offers an incoherent prayer in her heart, for she knows not what.

Esca’s part is not yet to be performed, and he is still in the background, preparing himself carefully for the struggle.

The rest of “The Family,” however, muster in force. Tall Rufus stalks to his appointed station with a calm business-like air that bodes no good to his adversary, whoever he may be. He has fought too often not to feel confident in his own invincible prowess; and when compelled to despatch a fallen foe, he will do it with sincere regret, but none the less dexterously and effectually for that. Hirpinus, too, assumes his usual air of jovial hilarity. There is a smile on his broad good-humored face; and though, notwithstanding the severity of his preparations, his huge muscles are still a trifle too full and lusty, he will be a formidable antagonist for any fighter whose proportions are less than those of a Hercules. As the crowd pass the different combatants in review, none, with the exception perhaps of Rufus, have more backers than their old favorite. Lutorius, too, notwithstanding his Gallic origin, which places him but one remove, as it were, from a barbarian, finds no slight favor with those who pride themselves on their experience in such matters. His great activity and endurance, combined with thorough knowledge of his weapon, have made him the victor in many a public contest. As Damasippus observes to his friend: “Lutorius can always tire out an adversary and despatch him at leisure;” to which Oarses replies, “If he be pitted to-day against Manlius, I will wager thee a thousand sesterces blood is not drawn in the first three assaults.”

The pairs had already been decided by lot; but amongst the score of combatants who were to fight to the death, these formidable champions were the most celebrated, and as such the especial favorites of the populace. Certain individuals in the crowd, who were sufficiently familiar with the gladiators to exchange a word of greeting, and to call them by their names, derived in consequence no small increase of importance amongst the bystanders.

11082The swordsmen, although now ranged in order round the arena, are destined, for a time at least, to remain inactive. The sports are to commence with a combat between a lately imported rhinoceros, and a Libyan tiger, already familiarly known to the public as having destroyed two or three Christian victims and a negro slave. It is only in the event of these animals being unwilling to fight, or becoming dangerous to the spectators, that Hippias will call in the assistance of his pupils for their destruction. In the mean time, they have an excellent view of the conflict, though perhaps it might be seen in greater comfort from the farther and safer side of the barrier.

Vitellius, with a feeble inclination of his head, signs to begin, and a portable wooden building which has been wheeled into the lists, creating no little curiosity, is now taken to pieces by a few strokes of the hammer. As the slaves carry away the dismembered boards, with the rapidity of men in terror of their lives, a huge, unwieldy beast stands disclosed, and the rhinoceros of which they have been talking for the last week bursts on the delighted eyes of the Roman public. These are perhaps a little disappointed at first, for the animal seems peaceably, not to say indolently, disposed. Taking no notice of the shouts which greet his appearance, he digs his horned muzzle into the sand in search of food, as though secure in the overlapping plates of armor that sway loosely on his enormous body, with every movement of his huge ungainly limbs. So intent are the spectators on this rare monster, that their attention is only directed to the farther end of the arena, by the restlessness which the rhinoceros at length exhibits. He stamps angrily with his broad flat feet, his short pointed tail is furiously agitated, and the gladiators who are near him, observe that his little eye is glowing like a coal. A long, low, dark object, lies coiled up under the barrier as though seeking shelter, nor is it till the second glance, that Valeria, whose interest, in common with that of the multitude, is fearfully excited, can make out the fawning, cruel head, the glaring eyes, and the striped sinewy form of the Libyan tiger.

In vain the people wait for him to commence the attack. Although he is sufficiently hungry, having been kept for more than a day without food, it is not his nature to carry on an open warfare. Damasippus and Oarses jeer him loudly as he skulks under the barrier; and Calchas cannot forbear whispering 11083 to Mariamne, that “a curse has been on the monster since he tore the brethren limb from limb, in that very place, for the glory of the true faith.”

The rhinoceros, however, seems disposed to take the initiative; with a short laboring trot he moves across the arena, leaving such deep footprints behind him, as sufficiently attest his enormous bulk and weight. There is a flash like real fire from the tiger’s eyes, hitherto only sullen and watchful — his waving tail describes as semicircle in the sand — and he coils himself more closely together, with a deep low growl; even now he is not disposed to fight save at an advantage.

A hundred thousand pairs of eyes, straining eagerly on the combatants, could scarce detect the exact moment at which that spring was made. All they can now discern is the broad mailed back of the rhinoceros swaying to and fro, as he kneels upon his enemy; and the grating of the tiger’s claws against the huge beast’s impenetrable armor, can be heard in the farthest corner of the gallery that surrounds the amphitheatre.

The leap was made as the rhinoceros turned his side for an instant towards his adversary; but with a quickness marvellous in a beast of such prodigious size, he moved his head round in time to receive it on the massive horn that armed his nose, driving the blunt instrument, from sheer muscular strength, right through the body of the tiger, and finishing his work by falling on him with his knees, and pressing his life out under that enormous weight.

then he rose unhurt, and blew the sand out of his nostrils, and left, as it seemed, unwillingly, the flattened, crushed, and mangled carcass, turning back to it once and again, with a horrible, yet ludicrous pertinacity, ere he suffered the Ethiopians who attended him to lure him out of the amphitheatre with a bundle or two of green vegetable food.

The people shouted and applauded loudly. Blood had been drawn, and their appetite was sharpened for slaughter. It was with open undisguised satisfaction that they counted the pairs of gladiators, and looked forward to the next act of the entertainment.

Again the trumpets sound, and the swordsmen range themselves in opposite bodies, all armed alike with a deep concave buckler, and a short, stabbing, two-edged blade; but distinguished by the color of their scarves. Wagers are rapidly made on the green and the red; so skilfully has the experienced 11084 Hippias selected and matched the combatants, that the oldest patrons of the sport confess themselves at a loss which to choose.

The bands advance against each other, three deep, in imitation of the real soldiers of the empire. At the first crash of collision, when steel begins to clink, as thrust and blow and parry are exchanged by these practised warriors, the approbation of the spectators rises to enthusiasm; but men’s voices are hushed, and they hold their breath when the strife begins to waver to and fro, and the ranks open out and disengage themselves, and blood is to be seen in patches on those athletic frames, and a few are already down, lying motionless where they fell.

The green is giving way, but the third rank has been economized, and its combatants are as yet fresh and untouched; these now advance to fill the gaps made among their comrades, and the fortunes of the day seem equalized once more.

And now the arena becomes a ghastly and forbidding sight; they die hard, these men, whose very trade is slaughter; but mortal agony cannot always suppress a groan, and it is pitiful to see some prostrate giant, supporting himself painfully on his hands, with drooping head and fast-closing eye fixed on the ground, while the life-stream is pouring from his chest into the thirsty sand.

It is real sad earnest, this representation of war, and resembles the battle-field in all save that no prisoners are taken and quarter is but rarely given. Occasionally, indeed, some vanquished champion, of more than common beauty, or who has displayed more than common address and courage, so wins on the favor of the spectators, that they sign for his life to be spared. Hands are turned outwards, with the thumb pointing to the earth, and the victor sheathes his sword, and retires with his worsted antagonist from the contest; but more generally the fallen man’s signal for mercy is neglected; ere the shout “A hit!” has died upon his ears, his despairing eye marks the thumbs of his judges, pointing upwards, and he disposes himself to “welcome the steel,” with a calm courage, worthy of a better cause.

The reserve, consisting of ten pairs of picked gladiators, has not yet been engaged. The green and the red have fought with nearly equal success; but when the trumpet has sounded 1108 a halt, and the dead have been dragged away by grappling-hooks, leaving long tracks of crimson in their wake, a careful enumeration of the survivors gives the victory by one to the latter color. Hippias, coming forward in a suit of burnished armor, declares as much, and is greeted with a round of applause. In all her pre-occupation, Valerian cannot refrain from a glance of approval at the handsome fencing-master; and Mariamne, who feels that Esca’s life hangs on the man’s skill and honesty, gazes at him with mingled awe and horror, as on some being of another world.

But the populace have little inclination to waste the precious moments in cheering Hippias, or in calculating loss and gain. Fresh wagers are, indeed, made on the matches about to take place; but the prevailing feeling over that numerous assemblage is one of morbid excitement and anticipation. The ten pairs of men now marching so proudly into the centre of the lists are pledged to fight to the death.

It would be a disgusting task to detail the scene of bloodshed; to dwell on the fierce courage wasted, and the brutal useless slaughter perpetrated in those Roman shambles; yet, sickening as was the sight, so inured were the people to such exhibitions, so completely imbued with a taste for the horrible, and so careless of human life, that scarcely an eye was turned away, scarcely a cheek grew paler, when a disabling gash was received, or a mortal blow driven home; and mothers with babies in their arms would bid the child turn its head to watch the death-pang on the pale stern face of some prostrate gladiator.

Licinius had looked upon carnage in many forms, yet a sad, grave disapproval sat on the general’s noble features. Once, after a glance at his kinswoman’s eager face, he turned from her with a gesture of anger and disgust; but Valeria was too intent upon the scene enacted within a few short paces to spare attention for anything besides, except, perhaps, the vague foreboding of evil that was gnawing at her heart, and to which such a moment of suspense as the present afforded a temporary relief.

Rufus and Manlius had been pitted against each other by lot. The taller frame and greater strength of the former were supposed to be balanced by the latter’s exquisite skill. Collars and bracelets were freely offered at even value amongst the senators and equestrians on each. While the other pairs 1108 were waging their strife with varying success in different parts of the amphitheatre, these had found themselves struggling near the barrier close under the seat occupied by Valeria. She could hear distinctly their hard-drawn breath; could read on each man’s face the stern set expression of one who has no hope save in victory; for whom defeat is inevitable and instant death. No wonder she sat, so still and spell-bound with her pale lips parted and her cold hands clenched.

The blood was pouring from more than one gash on the giant’s naked boy, yet Rufus seemed to have lost neither coolness nor strength. He continued to ply his adversary with blow on blow, pressing him, and following him up, till he drove him nearly against the barrier. It was obvious that Manlius, though still unwounded, was overmatched and overpowered. At length Valeria drew in her breath with a gasp, as if in pain. It seemed as if she, the spectator, winced from that fatal thrust, which was accepted so calmly by the gladiator whom it pierced. Rufus could scarcely believe he had succeeded in foiling his adversary’s defence, and driving it deftly home, so unmoved was the familiar face looking over its shield into his own — so steady and skilful was the return which instantaneously succeeded his attack. But that face was growing paler and paler with every pulsation. Valeria, gazing with wild fixed eyes, saw it wreathed in a strange sad smile, and Manlius reeled and fell where he stood, breaking his sword as he went down, and burying it beneath his body in the sand.

The other strode over him in act to strike. A natural impulse of habit or self-preservation bade the fallen man half raise his arm, with the gesture by which a gladiator was accustomed to implore the clemency of the populace, but he recollected himself, and let it drop proudly by his side. Then he looked kindly up in his victor’s face. “Through the heart, comrade,” said he, quietly, “for old friendship’s sake;” and he never winced nor quailed when the giant drove the blow home with all the strength that he could muster. They had fed at the same board, and drunk from the same wine-cup for years; and this was all he had it in his power to bestow upon his friend.

The people applauded loudly, but Valeria, who had heard the dead man’s last appeal, felt her eyes fill with tears; and Mariamne, who had raised her head to look, at this unlucky 11087 moment, buried it once more in her kinsman’s cloak, sick and trembling, ready to faint with pity, and dismay, and fear.

· · · · · · · ·

But a shout was ringing through the amphitheatre that roused the Jewish maiden effectually to the business of the day. It ha begun in some far-off corner with a mere whispered muttering, and had been taken up by spectator after spectator, till it swelled into a wild and deafening roar. “A Patrician! a Patrician!” vociferated the crowd, thirsting fiercely for fresh excitement, and palled with vulgar carnage, yearning to see the red blood flow from some scion of an illustrious house. The tumult soon reached such a height as to compel the attention of Vitellius, who summoned Hippias to his chair, and whispered a few sentences in his ear. This somewhat calmed the excitement; and while the fencing-master’s exertions cleared the arena of the dead and wounded, with whom it was encumbered, a general stir might have been observed throughout the assemblage, while each individual changed his position, and disposed himself more comfortably for sight-seeing, as is the custom of a crowd when anything of especial interest is about to take place. Ere long Damasippus and Oarses were observed to applaud loudly; and their example being followed by thousands of imitators, the clapping of hands, the stamping of feet, the cheers, and other vociferations rose with redoubled vigor, while Julius Placidus stepped gracefully into the centre of the arena, and made his obeisance to the crowd with his usual easy and somewhat insolent bearing.

The Tribune’s appearance was well calculated to excite the admiration of the spectators, no mean judges of the human form, accustomed as they were to scan and criticise it in the highest state of perfection. His graceful figure was naked and unarmed, save for a white linen tunic reaching to the knee, and although he wore rings of gold round his ankles, his feet were bare to ensure the necessary speed and activity demanded by his mode of attack. His long dark locks, carefully curled and perfumed for the occasion, and bound by a single golden fillet, floated carelessly over his neck, while his left shoulder was tastefully draped, as it were, by the folds of the dangling net, sprinkled and weighted with small leaden beads, and so disposes as to be whirled away at once without entanglement or delay upon its deadly errand. His right hand grasped the trident, a three-pronged lance, some seven feet in length, capable 11088 of inflicting a fatal wound; and the flourish with which he made it quiver round his head displayed a practised arm and a perfect knowledge of the offensive weapon.

To the shouts which greeted him — “Placidus! Placidus!” “Hail to the Tribune!” “Well done the Patrician Order!” and other such demonstrations of welcome — he replied by bowing repeatedly, especially directing his courtesies to that portion of the amphitheatre in which Valeria was placed. With all his acuteness, little did the Tribune guess how hateful he was at this moment to the very woman on whose behalf he was pledged to engage in mortal strife — little did he dream how earnest were her vows for his speedy humiliation and defeat. Valeria, sitting there with the red spots burning a deeper crimson in her cheeks, and her noble features set in a mask of stone, would have asked nothing better than to have leapt down from her seat, snatched up sword and buckler, of which she well knew the use, and done battle with him, then and there to the death.

The Tribune now walked proudly round the arena, nodding familiarly to his friends, a proceeding which called forth raptures of applause from Damasippus, Oarses, and other of his clients and freedmen. He halted under the chair of Cæsar, and saluted the emperor with marked deference; then, taking up a conspicuous position in the centre, and leaning on his trident, seemed to await the arrival of his antagonist.

He was not kept long in suspense. With his eyes riveted on Valeria, he observed the fixed color of her cheeks gradually suffusing face, neck, and bosom, to leave her as pale as marble when it faded, and turning round he beheld his enemy, marshalled into the lists by Hippias and Hirpinus — the latter, who had slain his man, thus finding himself at liberty to afford counsel and countenance to his young friend. The shouts which greeted the new comer were neither so long nor so lasting as those that did honor to the Tribune; nevertheless, if the interest excited by each were to be calculated by intensity rather than amount, the slave’s suffrages would have far exceeded those of his adversary.

Mariamne’s whole heart was in her eyes as she welcomed the glance of recognition he directed exclusively to her; and Valeria, turning from one to the other, felt a bitter pang shoot to her very marrow, as she instinctively acknowledged the existence of a rival.

11089Even at that moment of hideous suspense, a host of maddening feelings rushed through the Roman lady’s brain. Many a sunburnt peasant woman, jostled and bewildered in the crowd, envied that sumptuous dame with her place apart, her stately beauty, her rich apparel, and her blazing jewels; but the peasant woman would have rued the exchange had she been forced to take, with these advantages, the passions that were laying waste Valeria’s heart. Wounded pride, slighted love, doubt, fear, vacillation, and remorse are none the more endurable for being clothed in costly raiment, and trapped out with gems and gold.

While Mariamne, in her singleness of heart, had but one great and deadly fear — that he should fail — Valeria found room for a thousand anxieties and misgivings, of conflicting tendencies, and chafed under a distressing consciousness that she could not satisfy herself what it was she most dreaded or desired.

Unprejudiced and uninterested spectators, however, had but one opinion as to the chances of the Briton’s success. If anything could have added to the enthusiasm called forth by the appearance of Placidus, it was the patrician’s selection of so formidable an antagonist. Esca, making his obeisance to Cæsar, in the pride of his powerful form, and the bloom of his youth and beauty, armed, moreover, with helmet, shield, and sword, which he carried with the ease of one habituated to their use, appeared as invincible a champion as could have been chosen from the whole Roman empire.

Even Hirpinus, albeit a man experienced in the uncertainties of such contests, and cautious, if not in giving, at least in backing his opinion, whispered to Hippias that the patrician looked like a mere child by the side of their pupil, and offered to wager a flagon of the best Falernian “that he was carried out of the arena feet foremost within five minutes after the first attack, if he missed his throw!” To which the fencing-master, true, to his habits of reticence and assumed superiority, vouchsafed no reply save a contemptuous smile.

The adversaries took up their ground with exceeding caution. No advantage of sun or wind was allowed to either, and having been placed by Hippias at a distance of ten yards apart in the middle of the arena, neither moved a limb for several seconds, as they stood intently watching each other, themselves the centre on which all eyes were fixed. It was remarked that 11090 while Esca’s open brow bore only a look of calm resolute attention, there was an evil smile of malice stamped, as it were, upon the Tribune’s face — the one seemed an apt representation of Courage and Strength — the other of Hatred and Skill.

“He carries the front of a conqueror,” whispered Licinius to his kinswoman, regarding his slave with looks of anxious approval. “Trust me, Valeria, we shall win the day. Esca will gain his freedom; the gilded chariot and the white horses shall bring him and me to your door to-morrow morning, and that gaudy Tribune will have had a lesson, that I for one shall not be sorry to have been the means of bestowing on him.”

A bright smile lighted up Valeria’s face, but she looked from the speaker to a dark-haired girl in the crowd below, and the expression of her countenance changed till it grew as forbidding as the Tribune’s, while she replied with a careless laugh: —

“I care not who wins now, Licinius, since they are both in the lists. To tell the truth, I did but fear the courage of this Titan of yours might fail him at the last moment, and the match would not be fought out after all. Hippias tells me the Tribune is the best netsman he ever trained.”

He looked at her with a vague surprise; but following the direction of his kinswoman’s eyes, he could not but remark the obvious distress and agitation of the cloaked figure on which they were bent.

Mariamne, when she saw the Briton fairly placed, front to front with his adversary, had neither strength nor courage for more. Leaning against Calchas, the poor girl hid her face in her hands and wept as if her heart would break. Myrrhina, who, no more than her mistress, could have borne to be absent from such a spectacle, had forced her way into the crowd, accompanied by a few of Valeria’s favorite slaves.

Standing within three paces of the Jewess, that voluble damsel expatiated loudly on the appearance of the combatants, and her careless jests and sarcasms cut Mariamne to the quick. It was painful to hear her lover’s personal qualities canvassed as though he were some handsome beast of prey, and his chance of life and death balanced with heartless nicety by the flippant tongue of a waiting-maid; but there was yet a deeper sting in store for her even than this. Myrrhina, having got an audience, was nothing loath to profit by their attention. “I ’m 11091 sure,” said she, “whichever way the match goes I don’t know what my mistress will do. As for the Tribune, he would get out of his chariot any day on the bare stones to kiss the very ground she walks on; and yet, if he dare so much as to leave a scratch upon that handsome youth’s skin, he need never come to our doors again. Why, time after time have I hunted that boy all over the city to bring him home with me. And it ’s no light matter or a slave and a barbarian to have won the favor of the proudest lady in Rome. See how he looks up at her now, before they begin!”

The light words wounded very sore; and Mariamne raised her head for once glance at the Briton, half in fond appeal, half to protest, as it were, against the slander she had heard.

What she saw, however, let no room in her loving heart for any feeling save intense horror and suspense.

With his eye fixed on his adversary, Esca was advancing, inch by inch, like a tiger about to spring. Covering the lower part of his face and most of his body with his buckler, and holding his short two-edged sword with bended arm and threatening point, he crouched to at least a foot lower than his natural stature, and seemed to have every muscle and sinew braced, to dash in like lightning when the opportunity offered. A false movement, he well knew, would be fatal, and the difficulty was to come to close quarters, as, directly as he was within a certain distance, the deadly cast was sure to be made. Placidus, on the other hand, stood perfectly motionless. His eye was unusually accurate, and he could trust his practised arm to whirl the net abroad at the exact moment when its sweep would be irresistible. So he remained in the same collected attitude, his trident shifted into the left hand, his right foot advanced, his right arm wrapped in the gathered folds of the net which hung across his body, and covered the whole of his left side and shoulder. Once he tried a scornful gibe and smile to draw his enemy from his guard, but in vain; and though Esca, in return, made a feint with the same object, the former’s attitude remained immovable, and the latter’s snake-like advance continued with increasing caution and vigilance.

An inch beyond the fatal instance, Esca halted once more. For several seconds the combatants thus stood at bay, and the hundred thousand spectators crowded into that spacious amphitheatre held their breath, and watched them like one man.

At length the Briton made a false attack, prepared to 11092 spring back immediately and foil the netsman’s throw, but the wily Tribune was not to be deceived, and the only result was that, without appearing to shift his ground, he moved an arm’s length nearer his adversary. Then the Briton dashed in, and this time in fierce earnest. Foot, hand, and eye, all together, and so rapidly, that the Tribune’s throw flew harmless over his assailant’s head, Placidus only avoiding his deadly thrust by the catlike activity with which he leaped aside; then, turning round, he scoured across the arena for life, gathering his net for a fresh cast as he flow. “Coward!” hissed Valeria between her set teeth; while Mariamne breathed once more — nay, her bosom panted, and her eye sparkled with something like triumph at the approaching climax.

She was premature, however, in her satisfaction, and Valeria’s disdain was also undeserved. Though apparently flying for his life, Placidus was as cool and brave at that moment as when he entered the arena. Ear and eye were alike on the watch for the slightest false movement on the part of his pursuer; and ere he had half crossed the lists, his net was gathered up, and folded with deadly precision once more.

The Tribune especially prided himself on his speed of foot. It was on this quality that he chiefly depended for safety in a contest which at first sight appeared so unequal. He argued from the great strength of his adversary, that the latter would not be so pre-eminent in activity as himself; but he omitted to calculate the effects of a youth spent in the daily labors of the chase amongst the woods and mountains of Britain. Those following feet had many a time run down the wild goat over its native rocks.

Faster and faster fly the combatants, to the intense delight of the crowd, who specially affect this kind of combat for the pastime it thus affords. Speedy as is the Tribune, his foe draws nearer and nearer, and now, close to where Mariamne stands with Calchas, he is within a stride of his antagonist. His arm is up to strike! when a woman’s shriek rings through the amphitheatre, startling Vitellius on his throne, and the sword flies aimlessly from the Briton’s grasp as he falls forward on his face, and the impetus rolls him over and over in the sand.

This is no chance for him now. He is scarcely down ere the net whirls round him, and he is fatally and helplessly entangled in its folds. Mariamne gazes stupefied on the prostrate 11093 form, with stony face and a fixed unmeaning stare. Valeria springs to her feet in a sudden impulse, forgetting for the moment where she is.

Placidus, striding over his fallen enemy with his trident raised, and the old sneering smile deepening an hardening on his face, observed the cause of his downfall, and inwardly congratulated himself on the lucky chance which had alone prevented their positions from being reversed. The blood was streaming from a wound on Esca’s foot. It will be remembered that where Manlius fell, his sword was hurled under him in the sand. On removing his dead body the weapon escaped observation, and the Briton, treading in hot haste on the very spot where it lay concealed, had not only been severely lacerated, but tripped up and brought to the ground by the snare.

All this flashed through the conqueror’s mind, as he stood erect, prepared to deal a blow that should close all accounts, and looked up to Valeria for the fatal sign.

Maddened with rage and jealousy; sick, bewildered, and scarcely conscious of her actions, the Roman lady was about to give it, when Licinius seized her arms and held them down by force. Then, with a numerous party of friends and clients, he made a strong demonstration in favor of mercy. The speed of foot, too, displayed by the vanquished, and the obvious cause of his discomfiture, acted favorably on the majority of spectators. Such an array of hands turned outwards and pointing to the earth met the Tribune’s eye, that he could not but forbear his cruel purpose, so he gave his weapon to one of the attendants who had now entered the arena, took his cloak from the hands of another, and, with a graceful bow to the spectators, turned scornfully away from his fallen foe.

Esca, expecting nothing less than immediate death, had his eyes fixed on the drooping figure of Mariamne; but the poor girl had seen nothing since his fall. Her last moment of consciousness showed her a cloud of dust, a confused mass of twine, and an ominous figure with arm raised in act to strike; then barriers and arena, and eager faces and white garments, and the whole amphitheatre, pillars, sand, and sky, reeled ere they faded into darkness; sense and sight failed her at the same moment, and she fainted helplessly in her kinsman’s arms.