=============

ANTIQUITIES AND CURIOSITIES OF THE CHURCH.

________________

Pulpits.

BY THE REV. GEO. S. TYACK, B.A..

TO the modern Englishman the pulpit is almost synonymous with preaching; yet the earliest preachers did not use a pulpit, and the earliest pulpits were not necessarily for preaching. It is rather remarkable that a pulpit is only mentioned once in Holy Scripture, and once in the English Prayer Book; and in neither case in connection with a sermon. The former reference is the Book of Nehemiah (ch. viii., v. 4), where we are told that “Ezra the scribe stood upon a pulpit of wood,” in order to read to the people the words of the Divine law. The other allusion is in the rubric introductory to the Commination Service; the direction being that that office shall be said by the priest “in the Reading-Pew or Pulpit.” On the other hand there can be little question that in the early and the mediæval church the sermons were usually delivered from the altar steps.

It is true that the primitive churches were provided 122 with elevated platforms, ascended by steps and provided with book-rests, but these were not stands for preachers, but for readers. From these ambons, as they were called, the Gospels and lessons were read, as well as the acts of martyrs and the names of those who were to be commemorated. The ambo was also called the bema, and by St. Cyprian, the pulpitum, but when he speaks of being “placed in the pulpit,” or “coming to the pulpit,” he refers to his ordination to the minor order of readers only. Nevertheless, sermons were occasionally delivered from these erections; St. Chrysostom preached from the ambo at Constantinople, though both Socrates and Sozomen, in speaking of it, imply that it was an unusual thing to do so. St. Augustine also seems to have done the same at Hippo, in North Africa.

The ambo was sometimes adorned with a carved eagle in the front, and from it have been developed three separate articles of church furniture. Standing as it did at the entrance to the choir, in close connection with the chancel screen, it was given increased light and dignity, until it became the rood-loft, or elevated platform on the top of the screen itself. The simple 123 eagle-lectern is another form in which the ambo survives, and, lastly, it has given to us the raised tower-like pulpit of modern times.

Down to the Reformation period, the use of the term pulpit seems to have been somewhat indiscriminate in England. Grindal, in his injunctions to the archdeacons of the diocese of York, orders “that every parson, vicar, curate, and other minister within the said Archdeaconry, as well in places exempt as not exempt, when he readeth Morning and Evening Prayer, or any part thereof, shall stand in a pulpit to be erected for that purpose.” Again, in injunctions issued in 1547 under Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, we read, “In the time of High Mass, within every church, he that saith or singeth the same shall read, or cause to be read, the epistle and gospel of that Mass in English, and not in Latin, in the pulpit, or in such convenient place as the people may hear the same.” Latimer, however, in a sermon preached before King Edward VI. on April 12th, 1549, uses the term in its modern sense, when he compares a pulpit without a preacher to a bell lacking its clapper.

In the Mediæval Church, preaching was not nearly so commonly employed as it is to-day; 124 people were content then to offer their prayers and praises to God, without the addition of a sermon on every possible occasion; and it is significant that the pulpit is not included in any inventory of church furniture during the Middle Ages. Yet every priest was bound by the Constitutions of Archbishop Peckham, issued in 1281, to “publicly expound to his people four times a year, without any fantastical subtlety, the fourteen Articles of the Faith, the Ten Commandments of the decalogue, the two precepts of the Gospel, the seven works of mercy, the seven deadly sins, the seven principal virtues, and the seven sacraments of grace.” Among the Reformers the influences of preaching were greatly exalted; and we are not therefore surprised to find Henry Bullinger, “Minister of the Church at Zurich,” insisting on the absolute necessity of the pulpit, while the English divines, such as Whitgift and Latimer, speak of it as useful indeed, but not essential. It was not ordered as a requisite part of the furniture of the church, to be provided at the cost, if needful, of the parishioners, until the Canons of 1603, the eighty-third of which insists on the churchwardens or questmen providing “a comely and decent pulpit,” which is “to 125 be seemly kept for the preaching of God’s Word.”

It is not therefore surprising that pulpits of any great antiquity are far from common. Many ancient churches probably had none until the sixteenth or seventeenth century, and in other cases the pulpit was a light movable structure, like one still preserved at Hereford, which was only placed in the body of the church when 126 required, and which was little calculated to resist the wear and tear of time.

It was only about the end of the thirteenth century that pulpits in their present form were introduced at all into the West, although in the East, the name pyrgus (tower) sufficiently indicates the shape they had assumed in the ninth century.

The oldest wooden pulpit in England is said to be that at Fulbourne, a village not far from Cambridge; it dates from 1350. Another of about the same date is found at Lutterworth; it is a good example of the oak carving of its day, and claims additional notice from the fact that it was in all probability the pulpit used by the most famous of the rectors of Lutterworth, William Wiclif, whose incumbency extended from 1375 to 1384.

Three other pulpits recall the memory of two preachers, both famous, yet of very different types. The first is a heavy oak one in the curious church of Berwick-on-Tweed, which is alleged to have been removed from an older church in which John Knox officiated for some two years. A second pulpit associated with the Scottish reformer is now in the Museum of the 127 Society of Antiquaries of Scotland; this is the old pulpit of St. Giles’s, Edinburgh, and in its rugged solidity is very characteristic of the stern and unbending Calvinist who thundered from it his anathemas at the head of the unfortunate Mary, Queen of Scots.*

John Knox’s Pulpit. (From St. Giles’s Church, Edinburgh.)

The other is a specimen of some of the best carving of Grinling Gibbons 128 (1648-1721), and is in St. Andrew’s, Holborn, a church to which Dr. Sacheverell was presented in 1713.

The earliest Jacobean pulpit is at Sopley, in Hampshire, dating from 1606. Earl’s Barton has a good example of the same period, and Alford, Lincolnshire, another. Ancient pulpits of various dates are to be found, in wood, at Sudbury, Southwold, Hereford, and Winchester, and, in stone, at Worcester, Ripon, Combe, Nantwich, and Wolverhampton. An iron pulpit formerly stood in the Galilee at Durham Cathedral, from which a sermon was preached to the women on Sundays.

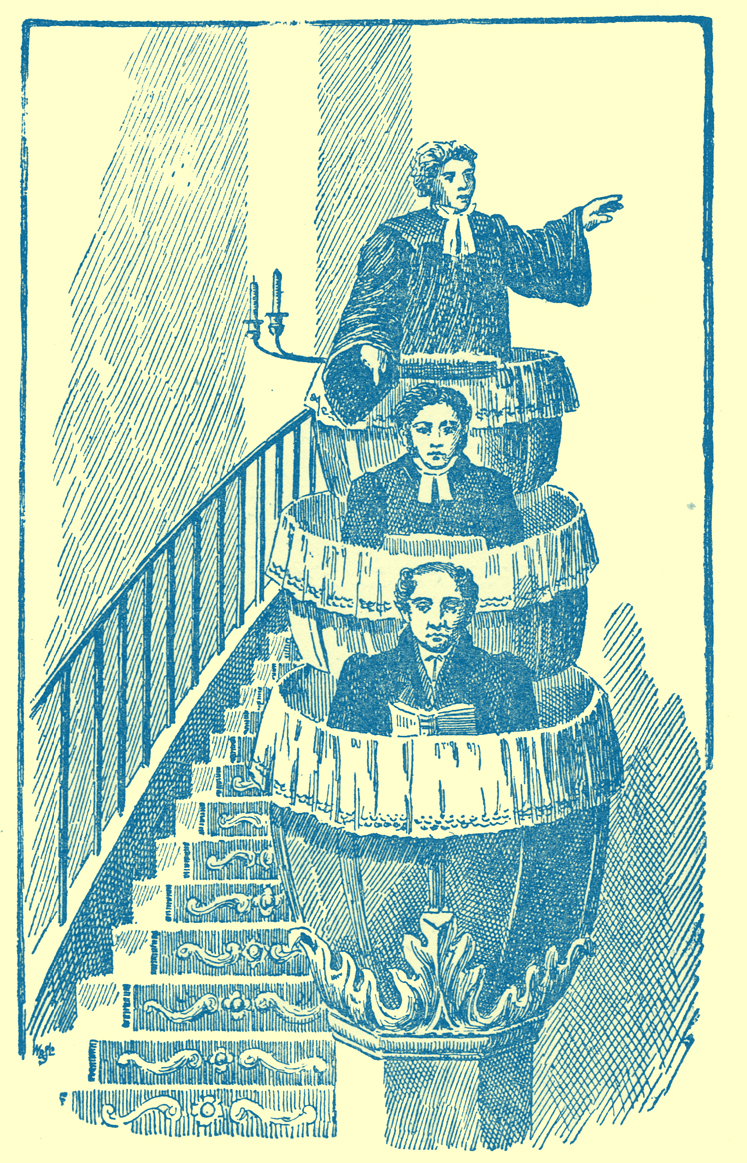

When the sermon came to occupy a more prominent place in public estimation, the pulpit naturally grew in importance. Monstrous galleries were reared around the church, the nave was cut up like a modern cattle market, into so many closed pens or pews, and the whole place was arranged for comfortable hearing rather than for devout worshipping. The people ceased to take much part in the service, except as listeners, and prayer and praise were left to the parson and the clerk, and the “Three decker” came into being.

The Three-decker.

In the lowest of the three pulpits sat the clerk, 129 monotonously mouthing the responses to the prayers read by the parson in the second pulpit just above his head. And at the close of the duet, the latter, donning black gown and bands, ascended to the “upper deck” to deliver his sermon of an hour or more. This hideous abomination in the way of ecclesiastical arrangements generally stood in the centre of the church, 130 towering like Babel up to heaven, and completely shutting out the altar from sight, proclaiming itself the only feature of importance in the House of God. Happily it is now as thoroughly a thing of the past as the antiquated warships from which, in derision, it was named; if examples of either now exist, they are curiosities only.

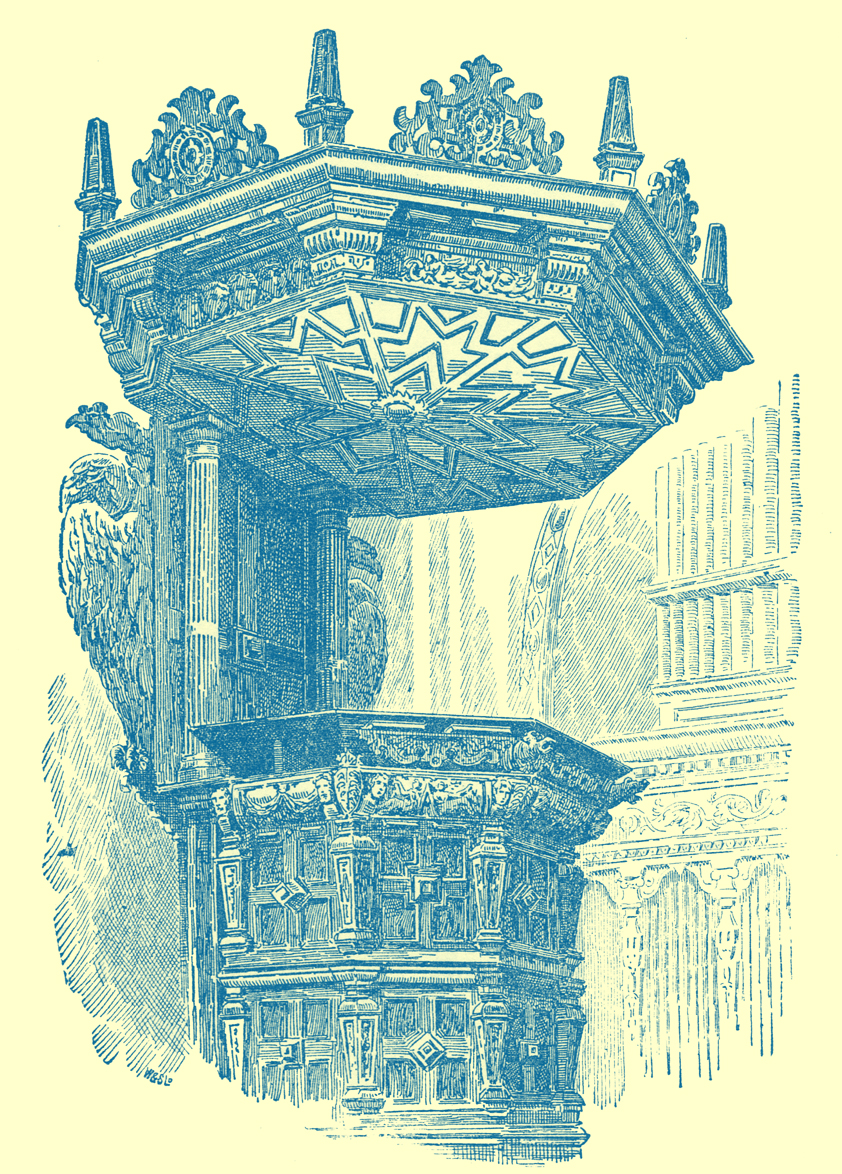

The destruction of the acoustic properties of an old church by the introduction of galleries and high-backed pews, and the ignorance of many of the later architects of the rules governing those acoustic properties, resulted in the invention of the sounding-board as an assistance to the preacher’s voice. These are seldom introduced now, but not a few instances remain. At St. John’s, Leeds — a church full of fine old oak carving — is a handsome one, and others may be seen at All Hallows, Barking; at Thaxted, in Essex; at Burgh-le-Marsh, Lincolnshire, and elsewhere. In churches of unusual size, as in St. Paul’s Cathedral, no doubt they are almost, if not quite, a necessity; and when in themselves handsomely designed, they are far from being an undignified addition to the pulpit.

Pulpit, St. John’s Church, Leeds.

Another adjunct to the pulpit, now extinct, but very needful during the Puritan era, was the 131 hour-glass. That was indeed the preaching age, when the preachers seemed determined, by the frequency and the length of their sermons, to atone for the deficiency of centuries. The Puritan divine, in the systematic treatment of his theme, divided his discourse into almost innumerable “heads;” and when the waning sands in his glass warned him that already an hour had been spent in oratory, it is on record that he sometimes did not scruple to turn the glass and enter on a second hour. The open-air pulpit at St. Paul’s Cross had, at the end of its career, a niche for an hour-glass. The Jacobean pulpit in St. Michael’s, at St. Alban’s, or Verulam, has an iron bracket for holding one, and at Belton Church, in North Lincolnshire, there is a similar bracket fixed to a pillar opposite the pulpit. St. Alban’s, Wood Street, London, has preserved its hour-glass intact.

An arrangement frequently found on the Continent is the attachment of the pulpit to a pillar in the nave, as, to quote one out of many examples, at the church of St. Maria in Trastevere, at Rome, where the pulpit, with its canopy or sounding-board, is bracketed out from the fourth column on the north side of the nave. An 132 English instance of this is supplied by the handsome pulpit of Holy Trinity Church, Coventry, which is attached to the north-east pier of the tower.

Some of the most remarkable pulpits in existence are to be found in Belgium. At Antwerp, Mechlin, Brussels, and elsewhere, are huge erections most beautifully carved, but not in the least suggestive of the purpose for which they were intended. In fact, a stranger might be pardoned for imagining that the splendid mass of sculpture was in each instance the original object aimed at, and that the place for the preacher was provided in the midst as an afterthought. At St. Gudule’s, in Brussels, is a wooden pulpit forming a group representing the expulsion of our first parents from Eden. Foliage is introduced, and birds and animals of various kinds are seen amid the branches, while, crowning the whole, is the Madonna with the Holy Child crushing the serpent’s head. At Mechlin the conversion of St. Paul is the subject chosen for representation, and we have a group of soldiers, and the Apostle fallen from a rearing horse. The call to the Apostleship of St. Peter and St. Andrew is shown us at St. Andrew’s, Antwerp; and the 133 Cathedral pulpit of that city is formed of allegorical figures of the four continents, accompanied by birds and “creeping things,” sporting amid spreading branches of trees. Louvain, Liège, and other towns have pulpits of a similar style. When it is remembered that the figures in these groups are for the most part life-sized, the incongruity will be realized of an arrangement which makes the preacher appear an impertinent intruder in the sculptured scene.

“Whatever ornaments we admit,” says Ruskin, speaking of pulpits, “ought clearly to be of a chaste, grave, and noble kind; and what furniture we employ, evidently more for the honouring of God’s Word than for the ease of the preacher.” These Belgian pulpits certainly were not designed to minister to “the ease of the preacher,” but in no other particular do they comply with the canon of the great critic.

At Wilton, near Salisbury, is a marble pulpit of handsome design, somewhat in the style of the better Continental ones; it is raised upon nine Corinthian columns, and reached by a winding stone stair. The great Parish Church of Yarmouth has a pulpit remarkable for its size; it has been described as “a great platform 134 enclosed with richly carved front, back, and sides.”

For several reasons wooden pulpits have generally been preferred to stone, and in our northern climate there can be no question that carved oak has a warmer and more satisfying look than the most beautiful work in marble, or other stone. At Exeter, Durham, and other cathedrals, at Clifton (All Saints), and in many other churches we have fine examples, mostly modern, of carved stone pulpits. But the oak, time-darkened, of some of the instances mentioned above, or of such a pulpit as that in St. Clement Danes in the Strand, has a richer effect.

Amongst our older stone pulpits may be named those at Molton, Bovey Tracey, and Chittlehampton; and to the wooden ones already cited should be added those at Stow, in Lincolnshire, and at Madeley.

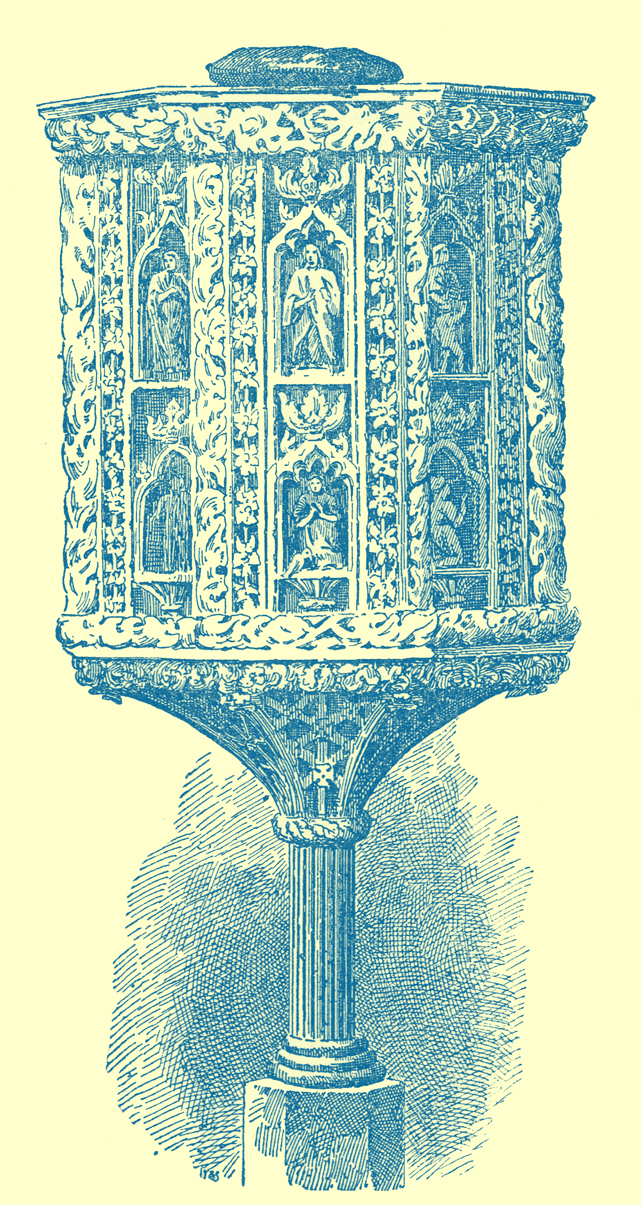

Stone Pulpit. St. Thomas à Becket, Bovey Tracey.

The open-air pulpits, or preaching crosses, once not uncommon in England, scarcely come within the scope of an article devoted to pulpits in the usual modern meaning. Suffice it to refer to St. Paul’s Cross as the most famous of them all, which after centuries of usefulness was destroyed in 1643 by the Long Parliament; and to name as 135 further examples the preaching crosses at Norwich, Hereford, Worcester, and Iron Acton, now all ruined or demolished.

Let a reference to a pulpit of Nature’s handiwork close our paper. Amidst the Derbyshire dales, not far from the village of Eyam, is a ravine known as Cucklet Church, which is overlooked by a lime-stone crag called Pulpit Rock. Here, 136 when the village was devastated by the Plague in 1665, the people assembled, sitting far asunder from each other on the grass, while from the rock above their faithful and devoted parish priest, William Mompesson, addressed to them words, whose earnest and faithful teaching must have been filled and thrilled with power from the ever-present death that overshadowed them. Few, if any, are the pulpits, whether in stately cathedral, or in the barest mission-church at home or abroad, that have witnessed more heroic zeal than the Pulpit Rock at Eyam.

===

Footnote

* The excellent illustration which we give of this pulpit is from “Bygone Scotland,” by David Maxwell, C.E., published by William Andrews & Co.

=============