=============

THE CHURCH TREASURY OF HISTORY, CUSTOM, FOLK-LORE, ETC.

________________

Animals of the Church, in Wood, Stone, and Bronze.

BY T. TINDALL WILDRIDGE.

THE presence of the animal representations so frequent in ecclesiastical architecture, and in some degree the forms of those representations, are mainly due to the deterioration at a remotely ancient period of the purer worship of a great deity — the sun. Of this god, adored by early man, various material forms were used as symbols, to which in many instances the worship contracted. The poets by their personification of attributes and emblematic figures were the first to impose the yoke of literalism upon mankind, which the priests, by their different use of exactly the same means in a more advanced mental atmosphere, did much to remove. The early churchmen, following the pagan leaders of thought, saw in every creature, its functions and its characteristics, the symbol of a spiritual or moral meaning applicable to man and his destiny.

Some symbols are great and enduring types, others insignificant and more or less absurd.

169Students of ecclesiastical zoology owe a debt of gratitude to Mr. E. P. Evans for his book* on the subject, which can henceforth scarcely be touched without reference to the work. It is not easy to explain the unreal, or to classify what seem at first sight the fanciful conceptions of a non-system in which every worker, were he tyro or master, was justified in evolving fresh conceptions and combinations, though none appears to have fully availed himself of the liberty. Classic art and lore are two of the chief channels by which symbolic representations reached Western Europe, and the want of precision or determination in the present subject is much akin to the vagueness and contradiction abounding in classic mythology itself. Thus the Greeks had three hundred epithets, mostly attributive, and wonderfully diverse, for Jupiter; with the Greeks the left hand was unlucky, but with the Romans both lucky and unlucky. So in mediæval symbolism the proneness to use the same figure for quite opposite purposes, according to the fancied exigencies of the moment, has left us a multitude of casual half-meanings from which to sift a reasonable scheme. 170 The cause, doubtless, of such a curious state of things being possible in classic times was the final popular semi-absence of real belief in the care or interest the gods had in man, or belief even in the existence of the myriad gods themselves. As the channel was muddy, the waters proved not clear.

We cannot accept Grimm’s decision that the whole mystery of the use of animal symbolism had its root in an ancient animal-worship founded on fear. In support of the attribution of supernatural, and therefore sacred, character to the brutes, it is alleged that they are not called by their real names, but propitiated by various flattering epithets, as “gold foot,” “broad brow,” “flash eye,” “forest brother,” and the like. Yet there may not be in the use of such terms anything but the hereditary outcome of the poetic temperament which characterises the Aryan race, the tendency of which was to speak of things by an attribute rather than a name, by allusion than by statement. Thus, long before the founding of Athens, the Aryan poet described the dawn clouds as red cows, and noonday clouds as flocks of sheep. So, too, in later classical days, when it was sought to convey the idea of a man being hanged, he was shewn seated in a swing; the word prison was 171 rarely used, house being employed instead; Acteon was not shewn metamorphosed into a stag torn by dogs, but simply seated on a deer-skin! This poetic hinting survives to our day, and in mediæval representation is best exampled by the manner in which the martyrs are delineated, each, for the most part, hale and hearty, but bearing the instrument or means by which he met his death. Gothic crudeness stepped in when St. Thomas, to all appearance with the usual epidermis, is shewn carrying his flayed-off skin in a basket. Other considerations are not wanting which weigh against the assertion of ancient man’s universal fear of the beasts. The earliest art work of man yet discovered is a rude sketch scratched upon a bone; it is a picture of the chase, in which Man is the hunter. In every phase of savagery extant, Man is the hunter, not the hunted. Even under such extreme conditions as go to prove fear, as in the case of the Indian tiger, the fear is not veneration; it is a fear qualified by intense hatred and the employment of traps, pitfalls, and other anti-worship engines. Where supernatural character is credited, as in the case of the hyena, there is a fear of killing him, but he is not worshipped. Moreover, in innumerable instances of 172 animal-worship, the gods include animals, birds, and insects, as well as trees, plants, minerals, etc., that have in nature neither marked noxious or beneficial influence. In all real animal worship there may be a large element of the idea of incarnation, but this would probably be late, and added to the primæval teachings of symbolism. Had fear been essential to animal worship, those beasts only which are night prowlers and powerful would, we might expect, be found as the objects of worship.

The line of the symbolists seems to be unbroken. When the early Gothic builders began their labour, they found ready to their hands a rich collection of ornament come down from the Classic, which had in its turn seized and mannerised the designs of the East. But when the builders of Western Europe woke up to the consciousness of how much could be done in architecture with ornament, and evolved the Decorated style, they took not only all that was to be found in the work of their predecessors but ran through wider fields of literature and folk-lore and of Nature, entering with zeal, and according to their various national idiosyncracies, renewing what they found, in lasting forms of wood, stone, and bronze.

173In one sense compound forms might be said to be, par excellence, “the Animals of the Church,” for they are to be met scarcely anywhere else but within the Church’s jurisdiction. Though outside the scope of this article, one example may be given. It represents a goat or sheep’s head hooded, with the body of a goose and the feet of a beast of prey. It is from a door moulding at Notre Dame, Paris, and is an instance of the difficulties which beset classification of mere fruits of fancy.

GOAT-HEAD, NOTRE DAME, PARIS.

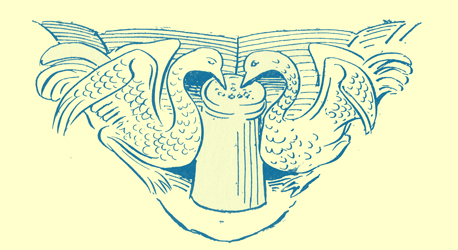

Many of the subjects of the mediæval church-carver are derived from symbols of sun-worship. One of the most frequent and recognisable of these is a design found on classic tombs, Asiatic cylinders, ancient tesselated pavements, etc., — the sun-myth in which the powers of darkness watch the altar of the sun, being simply figurative of each day being environed by nights. The general delineation is that of two eagles, but occasionally they are dragons or griffins, and in the numerous instances where we 174 meet the subject in our churches, the altar form is lost or mis-represented.

DARKNESS DEVOURING LIGHT,

ST. MARTIN’S, BERNE.

In a capital of Romanesque work at Berne, the devourers of day are two wyverns, i.e., eagles whose tails are those of scorpions or dragons. The altar has shrunk into a fruit at which they peck. In a miserere carving in Ripon Minster we find the fruit form of the same type — of blackberry appearance, with a deep calyx — but developed into a whole tree of clusters. Other carvings are similar.

DARKNESS DEVOURING LIGHT, BEVERLEY.

In one in Beverley Minster the dark devourers are shown as two swans, the ara here being retained as either a circular altar-form, from which the birds peck at the ashes of the fire, or as a vase of seed, according as we believe the artist to have, or have not, known his subject. Whether the fool’s hooded head, at which two birds peck (also at Beverley) may be regarded as Sol is questionable, though it will bear such interpretation.

In the dragon we have a great figure, belonging to the cult of sun-worship. He was the principle 175 of darkness, and his chief name in the old sun-myth was Typhon. Whether there is any foundation for his general form to be found among the terrible reptiles of the Pliocene age, which the geology of the future may shew to have slightly overlapped the advent of Man, can scarcely, with safety, be conjectured, yet the similarity of type met in all ages and countries would seem to point to something more than the ordinary transmission of an invented idea of what never was. The form of the dragon may be said to be that of a long-necked crocodile, winged and with supernal activity and malignity; there are, however, a large number of variants. In the old myth, Typhon is the desert, or winter, the period of darkness; he is slain by Horus (Hur, light, from the Sanscrit ush, to burn) the sun-god, i.e., the approach of Spring. Horus became a personal god with the Egyptians, 176 who held his festival, consonantly with his attributes, at the beginning of Spring, the precise day being the 23rd of April. The Greeks fed their fancy with the same myth covering the same natural phenomenon; Horus became Apollo who slew the Python; Perseus, the dragon-killer, is another personification of the sun as the winter-slayer. Thence descending to the middle ages, we find the same thing figured by the legendary slaughter of the dragon Fafnir by the hero Sigurd. Here the subject received a kind of sub-division in ancient times. Floods were the most disastrous effects of winter, and in the greater care of land in the middle ages, these were especially noticed and fought against. Mediæval records teem with accounts of floods, embanking, and the like. Now the great danger of a river flood is found constantly alluded to as a dragon, and various persons, who more or less effectually embanked, or otherwise prevented the recurrence of floods, are stated to have slain dragons. Even in the classic figurative history, the Python is said to have been the name of a river, and the evil thing slain by Perseus was a water-dragon. Of the mediæval dragons slain by the saints (who took the place of the classic 177 heroes in fable and story) two have names. One of these was the Dragon Gargouille, which ravaged the country round the Seine, and was said to have been slain by St. Romain of Rouen. Gargouille simply means a waterspout or gutter, and is the same word as the Gargoyle of our churches. The other was the Dragon Tarasque, which St. Martha killed at Aix-la-Chapelle. Tarasque is a word derived from the verb tarir, to drain, to dry up. There was another dragon which had its haunt in the Loire, and was slain by St. Florent. St. Philip slew a dragon at Hierapolis; three saints, St. Cado, Maudet, and Paull, slew Breton dragons; St. Keyne slew the Cornish dragon, while Donatus, Sts. Clement of Metz, George, Margaret, Michael, and Samson, Archbishop of Dol, and Pope Sylvester, all similarly distinguished themselves. Some of these are merely local, but among them is, doubtless, more than one instance of the cropping up of the old sun-myth. The survivor is certainly St. George, who definitely representing Horus and Apollo, is a notable instance of Christian adoption of a Pagan myth in its concrete form. The dragon borne in the Rogation processions is Typhon himself. Whether the word George (i.e., Earth-worker) 178 was selected as an allowable attribute of the sun may be open to objection, but St. George’s day is the 23rd of April, as in the case of Horus, who also was shewn mounted in Egyptian presentments. The carving here drawn is, however, of a St. George who has dismounted, and is given as affording a good example of what is sometimes seen in the paintings of the middle ages and elsewhere — the insignificant size of the vanquished reptile. This carving is on one of the interesting bench ends in the Choir of Holy Trinity Church, Hull.

ST. GEORGE AND DRAGON,

HOLY TRINITY CHURCH, HULL.

Where St. George slew the Dragon is not known, for it has been shewn that the Dragon’s Hill, in Berkshire, is an incorrect assignment, the “dragon” there killed, being the Celtic Pendragon Naud, defeated and slain by Cedric the Saxon.

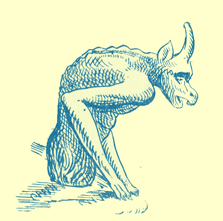

In its later symbolism as shewing the evil one 179 as a person, the dragon form is largely utilized with considerable modifications, to render the figure more or less human, a very suggestive necessity; the example is one of the numerous similar figures which adorn the Cathedral of Notre Dame, Paris.

SATAN, NOTRE DAME, PARIS.

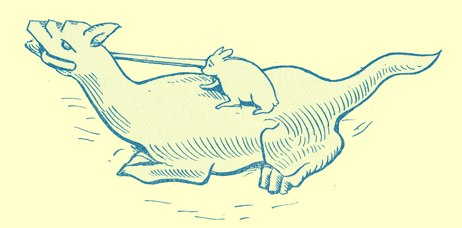

Not often is the dragon shewn without wings; a seat-carving at Beverley shews him thus, while on his back is seated a hare, the appropriate symbol of (among other things, including libidinousness) timidity. The hare has evidently the whip-hand of the evil one, and it is only necessary to find a name for the haler or reins with which he is being guided, to offer a forcible lesson.

Dragons are perhaps the most prolific of all the designs, for there can be no doubt at any time of the signification of the figures; a lion may mean the good or the bad, but a dragon is ever evil. Devouring men, in combat with lions, with monsters, with men, and with one another, or merely mocking Creation with their ugliness, dragons are ubiquitous. The word dragon is derived through the Latin draco, and the Greek drakōn, from the 180 Sanscrit dric, to see, from the power the reptile was said to have of destroying, like the basilisk, by the glare of its terrible eyes.

The Serra is a sea-dragon, which, excepting in the head, has all other characteristics of those of a goose or swan. An example at Beverley has in its breast the face of a man. The original Serra is a winged saw-fish.

HARE AND DRAGON, BEVERLEY.

The dragon was a Keltic ensign. Henry VII. in honour of his Welsh descent made it one of the supporters of the royal arms; it retained its place until the accession of James I., who supplanted it with the unicorn.

The lion may be said in the abstract to be symbolic of sovereignty or power, and its use or accompanying decoration determine whether it is intended as a type of good or evil.

The lion affords, in one of its frequent church 181 symbols met on the continent, a curious instance of erroneous natural history. It was believed that the lioness brought forth her young dead, and that after three days the lion by howling over them woke them to life, and this led representations of the incident to be taken as a suitable symbol of Christ and the Resurrection. Perhaps the belief arose from a hasty observation of the fact that the male lion sometimes kills his newborn young. Usually the female drives him away for a short time to obviate the catastrophe. The lion was also fabled never to close its eyes, a belief engendered by its nocturnal habits. This peculiarity led to its being placed at the doors of the sanctuaries, either as figures at the sides of the approach, or as heads in the knocker or hagoday. The persistency of design of these bronze knockers is somewhat curious. In many, the lion’s head is shewn with a human head at the opening 182 at the mouth.

KNOCKER AT ADEL CHURCH.

This may simply be devised to keep the ring-knocker in its place, or it may be a sort of hell’s mouth, and have a symbolical meaning, warning the fugitive taking refuge in the sanctuary, or perhaps his pursuers, of the penalties of trespass. But too much stress must not be laid upon this, as it is so evident that they are either from one another, or have a common original.

KNOCKER AT ALL SAINTS’ CHURCH, YORK.

Thus we see at Adel church, Yorkshire, All Saints’, York, and St. Gregory’s, Norwich, three bronze knockers, all of the fourteenth century, in which every detail is of the same design.

KNOCKER, ST. GREGORY’S CHURCH, NORWICH.

The lion mask, without the human head in the mouth, is seen in the earlier hagoday at the south door of Durham Cathedral, dating from 1140.

KNOCKER, DURHAM CATHEDRAL.

All the above examples have sharp-pointed ears; it is interesting to compare the fine lion knocker of Mayence, which has round ears, and 183 though in other respects similar to the Durham hagoday, is evidently of much later date.

LION KNOCKER, MAYENCE.

The lion at the feet of the recumbent effigies on tombs, signified at one time that the soul had its foot on Satan, but later, was the indication of robust hope, confidence, and vigilance: hence a dog occasionally holds the place. A lion at Hazeley, Oxfordshire, caresses the foot of the mailed effigy.

The representations of hell’s mouth by the open jaws of a beast, most frequently use the dragon, but sometimes the lion is met. The lion is generally to be taken as the emblem of the resurrection, and is assigned as the emblem of St. Mark, because his chief object was to give an account of the resurrection of Christ.

The cat has no high significance, and is generally found in domestic or folk-lore subjects of a comic nature. Two examples are given from Beverley. In one a monkey, having doubtless observed some process of combing or currying, 184 occupies itself with combing a cat.

MONKEY AND CAT, BEVERLEY.

In the other we have evidence of the long continuance of our nursery rhyme: —

“Hey diddle, diddle,

The cat and the fiddle,”

THE CAT AND THE FIDDLE, BEVERLEY.

which probably supplies a meaning to the “diddle” portion of the distich. A cat is charming four mice with the dulcet strains of the viol, while apparently she keeps a watchful and appreciative eye upon the largest and fattest. A companion carving shews her seizing her prey. In a miserere at Wells Cathedral, a carving of earlier date also shews us the mediæval cat and fiddle.

THE CAT AND FIDDLE, WELLS.

Probably the verse is the relic of a metrical satire on the worship of the moon. Another Wells carving shews us a hawk preying upon a hare.

HAWK AND HARE, WELLS.

The dog is seen at Beverley, helping himself to a fish from a cooking pot, while a man turns 185 from a blazing fire to chastise him; in another carving a dog is gnawing a bone. The dogs we find in carvings of the middle ages, appear to be a breed more robust than the ren or greyhound, but of that species.

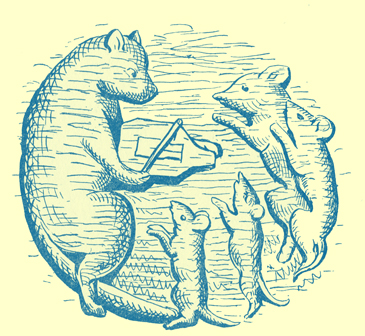

The character of the monkey was well grasped by mediæval artists, in whose time, indeed, the animal was more common as a household pet than at present. The same series of carvings at Beverley as that from which the cat is taken, includes a monkey riding a horse, pursued by the enraged owner, another holding a child in swaddling clothes, another examining a bottle after the manner of the doctor prognosticators, another chasing a cat with a club; while a good carving illustrates the story of the pedlar who was attacked by apes, who held him down while they distributed his hamper of wares. Others shew him being trained under the whip, playing the bagpipes while a bear dances, and using a cat as bagpipes by biting its tail. There is also 186 an example of what appears to be the cynocephali (simia innus) or dog-headed monkey, regarded by the Egyptians as a sacred animal. A seat-carving at Bristol shews a monkey on horseback, running off with stolen bags of grain.

The pedlar scene and the ape doctor is also shewn at Manchester and Bristol, where likewise are stone sculptures of the ape and fox episodes.

The pig is frequently met in church ornament, as probably very familiar to the sight of the artists, as well as possessing considerable symbolic import. It is most often used in burlesque representations. At Durham, Ripon, and Beverley choirs, are dances of pigs, in which the sow plays the bagpipes while her little ones trip their light fantastic hoofs. The Beverley carving is supported by two other pig-sculptures, in one a sow is shewn saddled, in the other playing a harp. There is a significance in this, for a pregnant sow was sacrificed yearly at the winter solstice, in, it is said, honour of Mercury, the 187 inventor of the harp. The Druids also sacrificed a sow at the winter solstice, doubtless a relic of sun-worship. A pig was sacrificed by the Athenians at the commencement of the deliberature and judicial assemblies held bi-monthly, and with them a sow, being, it is said, a corn-destroyer, was sacrificed yearly to Ceres. The hog is the symbol of St. Anthony, stated to have been in his youth a swineherd, and the smallest pig of a litter is sometimes called an “Anthony pig.” The example engraved is from one of the croches or elbow rests in the Choir of Beverley Minster.

PIG, BEVERLEY MINSTER.

The beaver when met in church work is generally found in a curled up and apparently sleeping attitude. But the meaning of the position is that the animal is biting off the castoreum bags, which it was fabled to do when hunted, so that its pursuers might take them, the object of their chase, and so relinquish further pursuit. The town 188 arms of Beverley shew the beaver in the posture for this self-excision. It is also met there as a cognizance in the Minstrel’s Chain, and on a seal, as having wings, displayed, and a carving of it on a bench end in the minster shews the same disposition. The beaver is a symbol of Christ in the point of view of self-sacrifice.

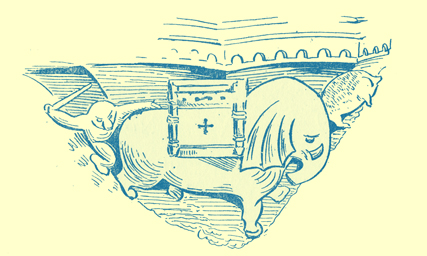

The earliest carving of an elephant in England is said to be at Exeter. A miserere at Beverley Minster, in which the animal bears a howdah, and one or more bold carvings on the heads of bench-ends in the same church are among the very few examples of church representations of elephants.

WIT AND WEIGHT, MONKEY, ELEPHANT, AND PIG, BEVERLEY MINSTER.

The elephant is one of the attributive names of Buddha, and is an emblem of Christ. Mediæval natural history relates that the female elephant brought forth her young in the water, in which respect it is a symbol of baptism. It is also sometimes an emblem of chastity.

Deer are generally shewn in simple natural attitudes and situations. A hart or hind signified solitude, and is the emblem of St. Hubert, likewise 189 of St. Julian and St. Eustace. Hunting scenes are not uncommon.

The camel is the symbol of submission; it appears on seat carvings at Boston and Beverley.

The serpent symbolizes, as well as the evil principle, also regeneration, and the love of Christ. In Egyptian and classic arts, the serpent signified reviving health, as in the beautiful symbolic figures of the well-known Portland or Barberini Vase of late classic date.

The otter and the ichneumon, as slayers of the crocodile, are figures of the power of Christ exercised against Satan.

The panther is a symbol of Christ, so also is the plover.

The wolf signified lewdness; the hyena unnatural vice.

190The squirrel is a figure of the striving with man of the Holy Spirit.

The unicorn, “whose horn is worth a city” says the Gule’s Horn book of 1609, on account of its being an infallible detectant and counteracter of poison, and a certain cure for epilepsy, was considered to live only in remote solitudes. The only hope of slaying or securing him was to use as bait a pure maiden, in whose lap he would nestle his head, and sleep to his destruction. Thus it became the symbol of chastity and purity, and was the emblem of the Virgin Mary, of St. Agatha, and St. Justinia. The horns, anciently prized as those of the unicorn, where it has been possible to submit them to modern examination, prove to be those of the narwhal. Like the lion the unicorn signified both the good 191 and bad, according to the inversion of meaning. The unicorn is not very frequent as a church animal. The example drawn, which is one of three at Beverley, is given because of its graceful horse-like form.

UNICORN, BEVERLEY MINSTER.

The sheep is often shewn in pastoral scenes, as shearings, etc. The cow and horse also generally figure in simple episodes of everyday life.

Two rams in the Beverley choir butt at each others so that their horns each form half of the astronomical sign (PIC) (Aries, the Ram).

The bear is generally treated as an animal familiar to the sight of the artists in situations of training, conveyance, trick performing, baiting, and is shewn muzzled. In a few cases the bear is used symbolically as a type of Satan.

The whale, in some departments of oriental 192 lore, is fabled to bear up the world, and that there is a constant chance of his diving, to which it is persuaded by the evil one, and so overwhelming the globe. This whale takes the place of the turtle or tortoise in Indian and the serpent in Scandinavian mythology, and points to the deluge theory, and perhaps tends to shew an early and forgotten appreciation of the gradual change of poles, and the necessary consequences, so admirably embodied in one of Huxley’s most suggestive Lay Sermons.

No account of the church animals would be complete without mention of the fox — Reynard the crafty — whom all affect to condemn, but who is respected for his successes, and is the most popular and most sung of all the animals.

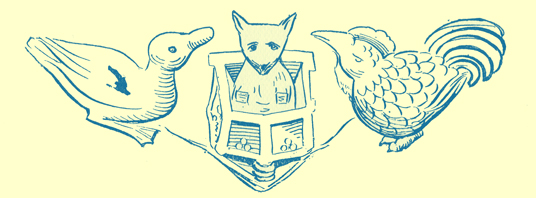

In the fox-carving here drawn, the fox is shewn, without robes, in a pulpit, preaching to a goose and a cock; his forepaws and what they may have held are broken off; but the cunning conveyed into his countenance preaches the whole 193 lesson. There are many similar examples; at Beverley Reynard is in full canonicals; among the misereres of the lesser church of Beverley (St. Mary’s), at Boston, Bristol, Nantwich, Ripon and Sherborne, are carvings of the fox preaching or hanging. Here also he is carved as prowling near two sleeping geese; as being hanged on a square gallows by a number of birds; as being resuscitated by an ape, who unties the rope from his neck, the rope terminating, to shew his awakening, in a Wake knot.

THE PREACHING FOX, RIPON.

It would be interesting to find the original of the design in which the fox is shewn preaching to a congregation of geese, while he is addressing them, as appears by a label, in these words: “Testis est mihi Deus, quam cupiam vos omnes visceribus meis,” from the first chapter of Philippians. In all the preaching scenes, this somewhat improper punning address may be 194 supposed to be uttered. It is noted as met in carving, in stained glass, and in manuscripts.

SAXON ANIMALS, ALDBOROUGH.

Perhaps, the oldest animal carving in this country is at Aldborough Church, Yorkshire (St. Bartholomew, probably originally Holy Trinity), built by Ulf, a Danish or Saxon lord of Holderness, who died in the reign of Edward the Confessor. It represents, in somewhat graceful lines, three animals, which appear to be a pair and their little one. Their species is so doubtful that they may be either vulpine or bovine.

Snails are occasionally met in church decoration. A snail at Boston is being driven up a hill by a monk; another at Beverley is being stabbed by a fashionably-attired gentleman of the fifteenth century. These are of different import from the mention of the snail in the romance of Reynard, where he is the standard-bearer, because he could so well scale walls! The Papal Church claimed to drive away snails by means of excommunicatory cursing.

The eagle, like the lion, affords a multitude of symbolisms. Its marked change of plumage after 195 moulting gave rise to the fable of its renewing its youth by plunging into a pool, used as the symbol of baptism, and by cremation. This latter idea, evolving the phœnix, gives another chief emblem of sun-worship. The Jews regarded it as an emblem of the renewal of life, as did the Romans, who carved it upon their burial-urns. There are curious coincidences in the language-changes of the words which are instances of the vagueness of symbolic cults. The Hebrew word chul means both sand and phœnix, and the Greek for both phœnix and palmtree is the same. The confusion is seen in Job xxix. 18, and Psalm xcii. 12, and in numerous carvings where the phœnix is shewn seated on a palmtree. Both are used in Christian art as symbolic of regeneration.

The pelican, “whose sons are nurs’t with bloode,” was a favourite subject of the wood-carver. The bird’s alleged habit of drawing blood from its own breast to feed its young caused it to be taken as the special emblem of Christ, and the symbol generally of Christian piety. Considerable trouble has been taken to shew that the pelican is an error for flamingo, because the latter bird can produce from the crop a blood secretion in an act of feeding, and because many ancient sculptures 196 shew the bird as much resembling a flamingo as a pelican. The pelican cannot be thus surrendered. There is no bird from a dodo to a crow which the inaccuracy of the church artist has not, in one instance or another, made his pelican resemble more than the actual pelican form. The true explanation is that the pelican’s beak is tipped with red or a reddish colour, its breast is frequently bare of feathers, and it has a habit of reposing its beak on its neck and breast, giving a considerable impression of self-wounding. In suggesting a re-reading as “flamingo” it was not taken into account that the pelican was said to feed its young with blood from its breast, and that the idea is one of sacrifice. Thus in “Birds Forbidden:” “She stabbeth deep her breast, self murtheresse through fondnesse to her broode,” as parents do everyday. Moreover, it is not necessary to find exact prototypes for all the attributes of the church animals, though frequently they have a foundation in imperfect observation of natural features. The seat of the Archbishop of York, in Beverley Minster, has a beautiful example of this symbol, and there is another on the canopy. The seat of the Precentor of the Minster has also, among other things, the same 197 subject, with the young pelicans in a basket. It is also the subject of a miserere at Boston.

The cock was the emblem of St. Peter; and of vigilance, of the Resurrection, courage, and liberality. Among the Beverley misereres are two cocks sparring on a barrel, a literal rendering of the old expression, cock-a-hoop. In another a cock is carved above the words clericus fabrici; this was John Sparke, who, in 1520, would, no doubt, have the supervision of the execution of these misereres. The vigilant bird is a well-chosen emblem to associate with a clerk of works. The clock, like the dragon, was a Welsh badge. Mr. Evans has misunderstood the above name, reading Sparke as “Wake,” and points an inference in connection with the bird and the name. John Sparke was the Receiver-General and Warden of the Fabric of Beverley Minster. The examination of some others of the Beverley carvings by Mr. Evans appears to have been as hasty, as his description in those cases are not marked by his usual accuracy. The cock was a Welsh and Gothic badge. The cock was dedicated to Apollo, Mars, and Mercury, and was sacrificed to Esculapius; all these, however, are one and the same, the solar deity, and the 198 connection is the salutation given by the cock to the rising sun.

The owl is the symbol of wisdom, emblem of Minerva, and the tutelary bird of Athens, but mediævally the symbol of darkness and unbelief, and, like the raven, a symbol of the Jews. At Beverley it is seen attacked by a possè of smaller birds, as not infrequently occurs in nature.

The hawk is most frequently seen in what may be termed natural scenes. At Wells a hawk is preying upon a hare; at Beverley it is hunting a bat. It is curious to note that the hawk in mediæval carving has generally a round and parrot-like head, the true falcon shape being rarely achieved.

Both the crow and the turtle-dove signify constancy and devotion, having alike the reputation of never taking a second mate.

The heron is a type of wisdom, the thrush of the grace of God.

The partridge, from a supposed or real inclination to rear the young of others, is a type of benevolence.

The hen and chickens is the emblem of God’s providence, and one of the special emblems of Christ; it was frequently adopted as a device in mediæval times.

199The raven was the symbol of concord and long life; but also in the later, and more involved, symbolism of the Fathers, typifies the Jews.

The dove was the type of conjugal fidelity; of rest, peace, and salvation; and every portion of its frame had its special lesson.

Birds in general were considered symbolic of the souls of martyrs; souls in general are shewn by the nakedness of the figures.

The fish is frequently met in the church. It was the symbol of chastity and one of the emblems of the Virgin Mary, as well as of Christ; the Greek word being used as the sacred acrostic, thus:

I èsus Jesus

C hristus Christ

TH eou of God

U ios the Son

S oter Saviour.

The elliptical or ovoidal form of the fish is used as an emblem known as the Vesica Piscis (fish-bladder); windows were made of this form, and it has been held that it is not without muliebraic reference.

The fish in classic mythology was credited with acting as the ferryman to bear the souls of the dead to the islands of bliss. It was a symbol of 200 Venus (and hence of the Virgin Mary, who took in Christian imagery the place of Aphrodite), and the use of Friday as a fish-eating day gave it the name it bears, dies veneris (French, vendredi), akin to the Saxon Fria-day, Fria being the Germanic equivalent of Venus. An eagle seizing a fish from the water is to be seen on the Norman doorway of Ribbeford Church, Worcestershire; the same is met among Keltic symbols, the attributed meaning being taking of the elect by Christ.

Other animals are met in church carving, but the chief have been mentioned, and sufficient to illustrate man’s aptitude for seizing on material forms to enforce on his fellows some spiritual or moral sentiment, or some fact scarcely patent to the general intelligence. We have, especially, seen that where long descent could be traced, mediæval symbolism rises out from the ashes of ancient myths, which can sometimes be seen to be relics of great primæval conceptions.

===

Footnotes

* Animal Symbolism in Ecclesiastical Architecture, by E. P. Evans. William Heineman, London, 1896.

=============