=============

THE CHURCH TREASURY OF HISTORY, CUSTOM, FOLK-LORE, ETC.

________________

BY THE REV. J. HUDSON. BARKER, B. A.

“MY book is the Nature of created things. In it, when I choose, I can read the words of God.” Such was Antony’s answer to the enquiry of the Greek philosopher or sophist who wondered how he could possibly live without books.

In that answer lies the keynote of much that seems to us inexplicable about the life of the hermits. The truest of their kind were Nature lovers. Their years were “bound each to each by natural piety.”

Anchorites and hermits like Paul and Antony of the Thebaid were the Wordsworths and Austins of ancient times, who saw and understood the beauties of God in the cliffs and cascades of the wilderness and the opening buds of the garden, even though they were not, like modern poets of nature, able to impart with their pens to others the thoughts inspired by mountain, rock, and sea. There has always been a certain class of men and women who has found the essence of life’s enjoyment 69 in solitary meditation, or who has seen the highest motive of life to be the recognising of God in the works of Nature.

Quite apart from Christianity the spirit of the hermit is natural to some. Even in the philosophies of Greece we find the Stoics and Cynics studiously keeping apart from their fellows lest sympathy and contact with others should be a source of contamination. The wizards and witches of the dark ages are probably lineal descendants of the recluses of some old-world religion of fairies and goblins and nature worship. No one can read Sir Edwin Arnold’s “Light of Asia,” without at once being reminded, in Buddha’s history, of the hermits of Christianity, while the fakirs of modern India prove that the spirit of the hermit is not confined to times nor limited to certain areas.

Again and again has the world at its crises had its course marvellously altered by the unveiling of one of these veiled prophets — the coming forth into the light of common day from the darkness of retirement for the stemming of warfare, for the relief of those afflicted with pestilence, or for the righting of wrongs, of some hermit who, having learned to control his own will, is fittest to control the will of others.

70Then the spirit of the hermit has appeared in a new light when giving vent to all the pent-up energies acquired by years of solitary retirement and meditation, as though he would atone for his seeming want of sympathy with his fellows by a superabundant supply in emergencies. Even so in Chrysostom’s early days the hermits came from their Syrian retirement and gained for Antioch pardon for the insult to the Statues. The Nitrian hermits came to nurse the plague-stricken Alexandrians, and Peter the Hermit fired the world with enthusiasm for the First Crusade.

There is something wildly fantastic and often sensationally romantic in the histories of hermits, yet beneath the sentiment and beneath the romance lies a reality — a stern reality of will’s endeavour to amputate from life the worst passions of nature, and often with them those which make nature loveable. There is a forgetfulness on the part of the hermit that the parable of the tares may be applied to the microcosmos of man’s own individual soul no less really than to the harvest field of God’s world.

Yet the hermit life was often in earlier times possibly an absolute necessity to many who entered upon it. Even in Anselm’s day the secular 71 life, synonymous with that of sin, or the religious life of ascetic rule were the only alternatives. With all its flaws and its alienation from social life, the system of the hermit emphasised the grandest principle of the Christian ethics — unselfishness — and both in the Grecian and Roman communities made practical what S. Paul himself dared not even hint at — the abolition of slavery; for it taught that there was no disgrace in manual labour, and it taught this not merely in theory but in practice, when the cultured courtiers of the Byzantine or Roman palaces retired to sow and reap on the banks of the Nile, or nurse the sick in the pestilential slums of the great cities.

The origin of the name “hermit” is interesting. Its form in the writings of Jerome and in Latin deeds of the Middle Ages show its derivation at once from έρῆμος — desert, for they adopted the word ἐρημιτης straight from the Greek Fathers. The hermit is essentially one who lives in the desert. Writers with a classical tinge kept the original form as late as Milton. In “Paradise Regained” we read: —

“Thou Spirit, who led’st this glorious Eremite

Into the desert, his victorious field.”

Though Spenser his predecessor in a pretty 72 description of a hermitage and chapel spells the word “hermite.”*

However, the Anglicised form had been used long before. In the original of Sir George Lancastre’s patent from Henry Earl of Northumberland in the 23rd year of Henry VIII., of the Conygarth with the Hermitage of Warkworth, it is repeatedly called interchangeably “Armitage” or “Harmytage.” In Dan Michel of Northgate’s curious old “Ayenbite of Inwit,” written in Kentish dialect about 1340 A.D., we come upon the word “ermitage” in the quaint parable of how the priest in the temple of Mahomet was converted into a monk of Christ, though synchronously with this Sir John Mandeville uses the other form in his “Voyage.” “At the desertes of Arabye he went into a chapelle where a eremyte dwelt.” By and by, in the same chatty book, the word is prefixed with the aspirate when he tells why Mahomet cursed wine. †

“And so befelle upon a nyght, that Machomete was dronken of gode wyn, and he felled on slepe, and his men toke Machometes swerd out of his schethe whils he slepte and therewith thei slowgh this heremyte, and putten his swerd al blody in his schethe aʒen. And at morwe, when he fond the heremyte ded, he was fulle sory and wroth, and wolde have don his men to deth; but thei alle with on 73 accord seyde that he himself had slayn him, whan he was dronken, and schewed him his swerd alle blody; and he trowed that thei hadden seyd soth. And then he cursed the wyn, and alle tho that drynken it.”

In the history of Monasticism, hermits hold two distinct positions. In the first place hermits themselves gave rise originally to communities of monks. The example of one hermit drew others into the desert beside him, and so the Cœnobitic monastery became naturally evolved. In the second place, under the evolved monastic system, some continually sighed for stricter rules and more solitary meditation, and so, withdrawing from the common life of the brotherhood, took up their abode in some cell, perhaps near to the monastery. Such was the case with St. Cuthbert, who, withdrawing from the monastery of Lindisfarne, took up his abode in the cell of Farne Island.

Great master-minds, like St. Martin of Tours, have led the van by first being hermits themselves, then founding Cœnobitic monasteries have subsequently retired to some more secluded spot among the mountains, or on some almost inaccessible ocean rock. Hence it is often difficult in investigating the origin of a hermitage near 74 unto an abbey, to decide whether the cell was established first, and then led to the formation of the neighbouring abbey, as the Cell of Godric led to the founding of Finchale, near Durham, or whether an abbey was founded first, and then cells branched off from it, for the retirement of those, who, like St. Cuthbert, wished for further seclusion, or for the missionary extension of religion in dark places. Such possibly was the cell formed at Westoe, as a branch from Jarrow, and to the self-same status probably was Jarrow itself degraded afterwards, when it became simply a subordinate cell dependent upon the Abbey of Durham.

In Mediæval England hermits seem often to have played the important part of officiating minister in places far from Abbey churches. Indeed for the matter of that, parish priests in lonely spots have in much later times really led hermit lives.

In the latter part of the twelfth century, in the time of Hugh de Baliol, of Bywell Hall, a certain hermit called Walter de Bolebec gave to the monastery of Kelso his hermitage and church of St. Mary’s, in the waste and forest south of Hexham, probably at Slaley. From which we 75 should judge that he had been the ministering spirit of the foresters, herdsmen, and moss-troopers of that region, until he founded for the Præmonstratensian canons the Abbey of St. Mary’s, at Blanchland, in 1175.

Generally with the hermit’s cell was a little chapel or oratory in which he could perform his own devotions, and to which he might invite the neighbouring cottagers to join him. Such seems to have been the object of the hermitage built at the end of the bridge at Stockport, in Cheshire, with its oratory of the fourteenth century.

To traverse the history of Christian hermits we must go to Eastern countries, ever the natural home of asceticism and mysticism, which are always tinged with fanaticism there, whether found in Jewish Essene or later Montanist.

The first recorded Christian hermit who prominently practised seclusion from his fellows was Paul of the Thebaid, whose life and miracles are so enthusiastically narrated by St. Jerome, the greatest advocate and promoter of asceticism, both for men and women, that the world has ever known.

Partly contemporary with Paul is Antony, 76 whose life, written by St. Athanasius, reads more like a romance of the Arabian nights, with the wondrous tales of demonology and animal subjection to the hermit’s will. Antony, in his ruined castle by the Red Sea, thought himself the first and best of hermits when he reached the age of ninety, but it was revealed to him that there was beyond him, and better than he, a hermit whom he must visit. After marvellous adventures with hippocentaurs, fauns, and satyrs, he arrived at the cave of Paul, whom he found to be 113 years old. An inseparable friendship sprang up between these two heroes of fasting and vigil, which lasted until Antony looked upon the form of the dead Paul still kneeling in prayer in his little oratory with stiffened hands uplifted to the skies, finding him even as the servants of David Livingstone (a man of modern times, but tinged with much of the good old hermit sprit which caused him to cut himself off from the luxuries of home life, that he might further the crusade of Christianity in the desert wilds of South Africa) found their master.

The example of these hero hermits was quickly followed by numbers, until the Thebaid of Egypt and the Nitrian Desert were thickly populated 77 with self-abnegating martyrs severing themselves from human love and human hope, as well as human sin.

The system spread rapidly into Syria, ripe ever for a revival of the Essene School, insomuch that soon it was difficult to get candidates for ordination, for the secluded life of meditation was held in higher esteem than the active missionary life of priesthood. The pages of “De Sacerdotio” show how difficult it was to uproot this doctrine even from the mind of St. Chrysostom, himself a hermit forcibly dragged to ordination and an active life.

But the growing error of the unpardonable nature of sin after baptism, caused yet more stringent application of ascetic exercises to prevent the yielding to passion, and developed that strange wild phase seen in the pillar saints, whose characteristic it was to raise themselves upon some solitary pillar many cubits high, and perhaps only three feet in diameter, and there undergo all changes of weather and all dreadful horrors, until the gruesome details make one sick to read them, and wonder that human will could so overmaster the feelings as to endure such torments voluntarily. But if the feelings 78 were blunted and overmastered, so was the intellect; for the illusions, the visions, and even the miracles of these and other hermits are but the “frothy working of a mind diseased.”

Simeon Stylites was the pioneer of these pillar saints, and received his surname from this fact. The little monologue by Lord Tennyson, called after him, gives anyone who can read between the lines a singularly vivid picture of the inner working of his soul, and the motives that led to this strange life. Simeon was imitated by very many, and the fame of his saintliness and pseudo-miracles caused a perfect forest of pillars to begin to rise throughout Syria, some of the occupants of which even outsimeoned Simeon in the tenacity of their endurance.

The spirit of the hermit passed to the Latin world, but here it received a modulation due partly to the general legal constitution of the Latin world, partly to the Augustinian Theology of the age, and the solitary hermit founded the Cœnobitic monastery, with its rules and order without the wild impetuous fanaticism and mysticism that marked the Eastern monk.

The monks of the west, in the spirit of the west, tended to the study of men and human 79 nature, and the works of man in literature and art. Yet some there are imbued with a love of Nature in her wildness, who can mediate on God and His works better in solitude, and so we find still the hermit leaving his monastic cell, and taking up his abode in mountain cave, or on some rocky islet even in the west.

Again as in the east the Eremitic system is the check to serfdom; side by side with the overweening Norman baron is the baronial abbot laying aside his robes of office, and passing out to the hermit life, tilling the ground, digging out his cell, and showing it is no disgrace to work, but a glory.

In England, we more frequently find instances 80 of the Anchorite, who has a little chamber in connection with some abbey or church, wherein he dwells. Sometimes he immures himself so that he cannot get out, and is fed through some hole in his enclosure.

HERMITS AND HERMITAGES.

The picture we give of “Hermits and Hermitages” is from a M.S. Book of Hours, executed for Richard II. (British Museum, Domitian, A. xvii., folio 4 v.). “The artist” says the Rev. Edward L. Cutts, “probably intended to represent the old hermits of the Egyptian desert, Piers Ploughman’s —

“Holy eremites

That lived wild in woods

With bears and lions;”

but after the custom of mediæval art, he has introduced the scenery, costume, and architecture of his own time. Erase the bears which stand for the whole tribe of outlandish beasts, and we have a very pretty bit of English mountain scenery. The stags are characteristic enough of the scenery of mediæval England. The hermitage on the right seems to be of the ruder sort, made in part of wattled work. On the left we have the more usual hermitage of stone, with the little chapel bell, in the bell-cot on the gable. The 81 venerable old hermit, coming out of the doorway, is a charming illustration of the typical hermit, with his long beard, and his form bowed by age, leaning with one hand on his cross-staff, and carrying his rosary in the other.”

The hermitage or reclusorium at Hambledon, Hants., is connected with a large thirteenth century church. Built in the angle between the tower and the west end of the south aisle, its date is probably of the fourteenth century. It consisted of two large rooms, one above the other. The upper one, of which the floor is now removed, shows a drain pipe still remaining through the wall to the exterior, and this room probably the recluse would use as his ordinary dwelling-room and kitchen. There was a door in the upper room leading by a gallery through the south aisle to the parvise of the adjacent porch, so that our friend had the use of three good-sized rooms. The original wooden door in the wall of the parvise still remains. Nothing has been ascertained as to the person for whom this hospitium was erected. He is spoken of in some old documents at Winchester as the hermit of Hambledon, but the size of the rooms points to some different manner of life to that usually 82 followed by a recluse. He may have been the sacristan, or conductor of the church music, or in some other way devoted his time and talents to the service of the church. There is no outer door, but access was obtained from the church of which the building is now used as the vestry.

Another anchorage at Walpole St. Andrews, Norfolk, is a much smaller edifice, and seems meant as a convenient receptacle for a devotee to immure himself therein alive. This cell of a holy man was probably much resorted to by superstitious dwellers in marshland.

Against the north wall of the church of Ss. Mary and Cuthbert, at Chester-le-Street, was formerly an anchorage of four rooms. In later times this was used as the vicarage.

Similar instances are found at Durham Cathedral. Over the great north doorway, with its dragon-head knocker, was a little room, wherein stayed two monks, ever ready to go down and open the door for the refugee when he rang the knocker of sanctuary. Again between the north aisle of the choir and the Nine Altars was a grand porch called the Anchorage. “Here dwelt an anchorite, whereunto the priors 83 very much resorted, both for the excellency of the place, as also to hear mass, standing so conveniently unto the high altar, and withal so near a neighbour to the shrine of St. Cuthbert.”

There was a regular service in the Salisbury Manual for the walling in of anchorites.

Even women thus immured themselves, like those three nuns at Kingston Tarrant, in Dorsetshire, for whom the thirteenth century “Ancren Riwle” was written.

Hagioscopes in the north or south side of the chancel from little chambers behind in so many churches testify to the frequency of these immured anchorites. This, indeed, was the common form of hermit in the south and midland counties, and to this kind the darker aspects of the ascetic hermit, unhealthy Christianity, weakened intellect, and demoralised humanity, essentially belong.

The Fen district in its ancient state, provided scope for hermits of the type of Antony and Paul. There in the rich, wild, green pasturage, surrounded by marshes covered with water-lilies, and swarming with pike and perch, where the kingfishers dart and the wild ducks plunge, St. Guthlac made his hermit home in the seventh century.

84He had been a warrior, but he had grown tired of slaying and sinning, and so he left his ancestral and princely home for the little green mound where he made his cell, and whereon, after fifteen years of self-abnegation, of starvation, ague, and fever had sent him to his long home, there arose the magnificent Abbey of Crowland. Over another of these fen heroes, St. Botolph, arose another shrine, and round it gathered the town which still bears his name, Botolph’s town or Boston.

But it is the mountainous North, and especially the romantic crags and dells of the borderland, that in England proved the best ground for the nature-loving hermit in his purest and holiest form. All over the north country there are dotted places which still go by the name of Armitage or Hermitage, showing plainly the nature of the quondam inhabitant. Similarly in Scotland and Ireland the prefix kil, kel, or cul, shows at once the place where once upon a time there was no habitation but the “cell” of some hermit, or a group of “cells” of the ancient British form of monastery anterior to the introduction of the Benedictine rule.

There is no history that is truer than that gained from place-names.

85Here is the hermitage of St. John’s Lee, near Hexham, a gentleman’s residence, with splendid gardens, and some of the finest beeches in England, but its name shows that this was the spot whither St. John of Beverley used to retire for weeks of meditation and devotion from the busy life of the Hexham Abbey in the seventh century. From some similar cause no doubt comes the name of the Hermitage, the residence of Sir Lindsay Wood, at Chester-le-Street.

From a hermitage in Eskdale, near Whitby, Godric, a native of Walpole in Norfolk, came to Durham, during the bishopric of Flambard (1099-1128). Acting as verger at St. Giles’, and listening to the lessons of the children at the school of St. Mary-le-Bow, he learnt the psalter by heart, and once more sought retirement in a cell he constructed for himself on the north bank of the Wear, near the spot where the handsome ruins of Finchale now stand.

His biography by Reginald, dedicated to Hugh Pudsey, reminds us very much in its extravagant demonology and miracle-working, of the lives of Paul and Antony. Again we hear of the extreme steps taken for self-discipline, but a new feature is added; night after night, even in the 86 cold winter months, St. Godric will stand up to his neck in the icy Wear all the night through, just as St. Drycthelm of Melrose did in the river Tweed in Bede’s day, and as Charles Reade makes his hero do in that finest of all historical novels “The Cloister and the Hearth.”

North of Durham and Finchale, just before reaching Gateshead, we come to Ayton Bank, respecting which there is a very interesting document in existence: —

“HEREMITARIUM DE EIGHTON .

“Johannes dei gra. Dunelm. Episcopus omnibus ad quos presentes literæ pervenerint salutem Sciatis quod de gratia nostra speciali concessimus Roberto Lamb, Heremitae, unam acram vasti nostri ad finem borealem villae de Eighton juxta altam viam ducentem, versus Gateshead vid. ex parte occidentali dictae viae prope rivulum descendentem de fonte vocato Scotteswell pro quadam Capella et Heremitagio per ipsum ibidem in honore S. Trinitatis edificandis, habend. et tenend. eidem Roberto ad terminum vitae suae de elemosina nostra libere et quiete ab omni servitio seculari ad serviendum Deo ibidem et orando pro nobis et pro predecessoribus ac successoribus nostris.

“In cujus &c. Dat. apud Dunelm 20 die Maii Ao. Pont. Sexti Rot. Fordam Ao 6, 1387.”

The Life of St. Cuthbert shows him a hermit at Doil, in Scotland, in his early days, and again in his declining years on the rocky Farne Island, where the seabirds learn to love him. The 87 miracles alleged about him and other hermits in respect to wild animals, are not hard to understand when we consider the wonderful scope they had for the practical study of Natural history, and how marvellous their knowledge would appear to the untutored visitors. But for ages the miracle-working of St. Cuthbert, and of the spirit of St. Cuthbert, was believed in by the superstitious northerners of mediæval times, and had they not proof for ocular demonstration? When the storm subsided, throughout which the ringing of St. Cuthbert’s hammer had been heard, and they went upon his island, did they not pick up the beads which he had wrought? We know them to be simply the entrochi of Geology, but they did not, and so they called them Cuthbert’s beads, just as they called the ammonites of Yorkshire, Hilda’s petrified serpents.

Away in the bosom of the Cumbrian hills, on a little island near the centre of Derwentwater, still stand the ruins of the little chapel built over the shrine of St. Herbert, the intimate friend of St. Cuthbert. On that island St. Herbert spent his hermit life, visited occasionally by his friends (perhaps from Crosthwaite, where St. Kentigern had established his Cumbrian mission), who, 88 starting from the little pine-clothed promontory on the eastern side of the lake, bequeathed to it the name of the “Friars’ Crag.” There in the scene so loved by Wordsworth, St. Herbert closed his life on the self-same day as his friend St. Cuthbert, on his rocky isle. Thus was their prayer strangely answered.

St. Cuthbert is the typical hermit of the sea. Others besides him have found in the sad sound of its waves and the ever-changing lights upon its surface, groundwork for passive contemplation and perpetual prayer. St. Brendan found it on the bosom of the ocean, seeking the land of rest, the “Promised Land.” St. Regulus found it on the shores of Fife, when he landed with the relics of Scotland’s patron saint, and established his hermitage on the spot where, in later years, grew the city of St. Andrews.

Coquet Isle, off Warkworth Harbour, was itself a cell of retirement, belonging to the Benedictine monks of Tynemouth.

But the mention of Warkworth brings us to the most entrancingly romantic of all the hermit stories, the pathetic tale so graphically told by Bishop Percy, in the style of the old Northumbrian Ballads.

Nowhere in the world is there a more interesting 89 anchorage, both for its architectural design and its origin, than Warkworth Hermitage

There lived at Bothal Castle, about the time of Edward III., a young chieftain of the name of Sir Bertram, whose love for the heiress of the house of Widdrington was reciprocated, and moreover was approved of by the lady’s parents. But before consenting to marriage she required her suitor to prove his valour, and sent him a helmet for use against the Scots. In a subsequent border raid, Sir Bertram was sorely wounded, and was carried to Wark Castle by the Tweed, to be healed. His promised bride, hurrying across the Cheviot moorlands to nurse him was captured by a Scottish nobleman who had been an unsuccessful suitor for her hand, and her attendants were killed. A week later, Sir Bertram recovering, in anxiety at no tidings reaching him from the lady, goes to her home and finds that she had set out for Wark, No trace of her whereabouts being discovered, he comes to the conclusion that some mosstroopers have carried her off. Consequently, he and his brother set out in different directions under disguise to seek her. By chance, unknown to each other, they discover her prison about the same time. The brother in highland disguise is just carrying 90 her off to safety at night when Sir Bertram in minstrel garb comes upon them and slays his brother, and the lady, discovering the mistake too late, throws herself between them and is herself slain. Henceforward the luckless victim of these sad circumstances, having been with difficulty restrained from committing suicide in his frenzy, gave himself up to the hermit life of fasting and prayer.

His friend, Earl Percy, gave to him the sequestered spot on the north bank of the Coquet, near Warkworth, where he spent his fifty remaining years in excavating in the solid freestone rock a beautiful little Gothic chapel, which still remains, in architecture of the style of Edward III.,’s time.

WARKWORTH HERMITAGE.

The little grotto contains three apartments, which have been named the chapel, the sacristy, and the antechapel. Outside of these by mason-work the hermit’s (or probably his successors’) dwelling-room and bed-room were built.

The chapel is still entire; the other apartments have been partly broken by the fall of rock.

The chapel is about eighteen feet long, with a width and height of about seven-and-a-half feet. At the east end, reached by two steps, is a handsome stone altar, having the upper plane edged 91 with moulding. In the centre of the wall behind is a niche for a crucifix, with the remains of a glory. On one side of the altar is a beautiful Gothic window, which admitted light to the sacristy. On the opposite side is a cenotaph bearing the recumbent effigy of a lady. Her feet rest upon the figure 92 of a dog, as the symbol of fidelity. Beneath is the figure of a bull’s head, the crest of the lady’s family. Kneeling at the foot of the tomb, with his head resting on his right hand, is the figure of the hermit. A door in the chapel led to an inner apartment containing an altar like that in the chapel, and a recess in the wall for the reception of a bed, whereon one of moderate size might sleep. This then was the hermit’s own sleeping apartment. Above the entrance to it is a shield, cut in the stone, and sculptured thereon are the cross, the crown, and the spear, as emblems of the Passion.

Leaving the chapel, we turn and look at the inscription, now illegible, but which once ran: — “Fuerunt mihi lacrymae meae panes die ac nocte,” and it seems like the motto not of this hermit alone but of every genuine hermit throughout Christendom; “My tears have been my meat day and night.”

Outside we find the hermit’s well, and a rock-hewn flight of steps to the left of the grotto, leading to the summit of the cliff, where he had his little garden, and whence he might gaze across the Vale of Coquet. This garden is now covered thick with oaks.

A series of hermits followed him in line, until 93 the Reformation swept away hermitages and anchorages along with the monasteries.

The last hermit at Warkworth seems to have been Sir George Lancastre, to whom was granted by the Earl of Northumberland a patent of twenty marks a year and other privileges in consideration of his daily prayers for the Earl and his ancestors in 1532. This document is still extant.

EXTERIOR VIEW OF ST. ROBERT’S CHAPEL,

KNARESBOROUGH.

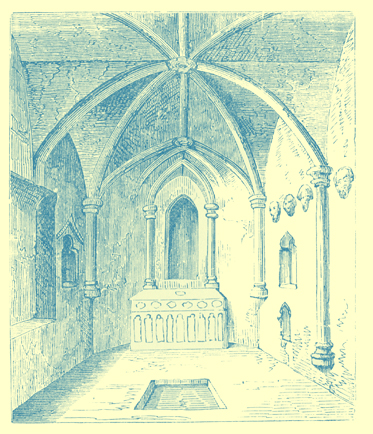

At Knaresborough, Yorkshire, still remains an interesting example of a hermitage. It is known as St. Robert’s Chapel, and is hewn out of the rock, at the bottom of a cliff. We give pictures of the exterior and interior of the chapel. The chapel appears to have also been the hermit’s living-room. Our illustrations are from Carter’s “Ancient Architecture.”

INTERIOR VIEW OF ST. ROBERT’S CHAPEL,

KNARESBOROUGH.

The Reformation swept away almost all vestiges of the technical religious hermit from England, but it cannot kill the spirit of the hermit. Subsequently we find it exhibiting itself in very eccentric forms in our country.

In 1696 died John Bigg, the hermit of Denton. Formerly clerk to the regicide Judge Mayne, at the Restoration he retired to a cave, and lived on charity, though he never asked for anything but leather, which he kept patching on his already 94 overladen shoes. These remarkable shoes were preserved, one in the Ashmolean Museum, and the other at Denton Hall.

In 1863 there was living near Ashby-de-la-Zouch an eccentric character who named himself “The old Hermit of Newton Burgoland.” His mania was political rather than religious. His own motto was “True hermits throughout every age have been the firm abettors of freedom,” and the actions of his life were all intended to exhibit some political, social, or religious symbolism. The garments which he wore, and the plots in which his garden were laid out, all symbolised some quaint idea. Thus one hat of helmet shape represented the idea “Fight for the birthright of conscience, love, life, property, and national independence.” Another of his twenty symbolic hats shaped like a beehive represented the thought “The toils of 95 industry are sweet; a wise people live at peace.”

To such a weak aimless end had the hermit life decayed.

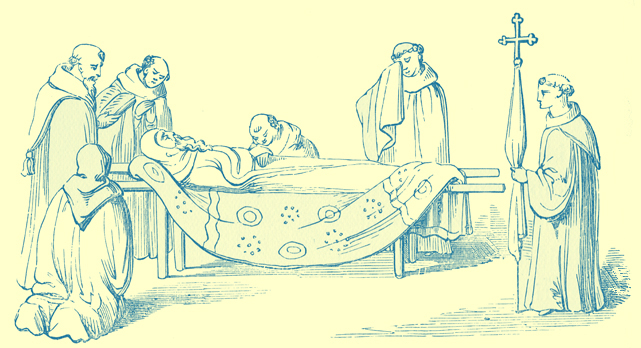

FUNERAL SERVICE OF A HERMIT.

We give an illustration of the funeral of a hermit, which is one of a group in a fine picture of “St. Jerome,” by Cosimo Roselli (who lived from 1439 to 1506), in the National Gallery. “It represents,” says the Rev. Edward L. Cutts, in his “Scenes and Characters of the Middle Ages, “a number of hermits mourning over one of their brethren, while a priest, in the robes proper to his office, stands at the head of the bier and says prayers, and his deacon stands at the foot holding a processional cross. The contrast between the robes of the priest and those of the hermits is lost in the woodcut; in the original the priest’s cope and amice are coloured red, while those of the hermits are tinted with light brown.” It will be 96 observed that he is to be interred without a coffin, which was customary amongst members of religious orders in bygone times.

Yet, since nothing dies, but only all things change, all that was great and good in the hermit spirit has but passed on into other forms, for still we find poets of nature and self-denying souls, and even the hermit form itself may phœnix-life arise again out of the ashes of the frivolity and secularism of the age as an overstrained reaction from the past, as it did of old. Who can tell?

It will not seem more strange to us than it did to the calm-souled fellow-Christians of Paul and Antony, or the Roman contemporaries of Jerome and Eustochium.

===

Footnotes

* Fairy Queen, Bk. vi., Canto v.

† “The Voiage and Travaile of Sir John Maundeville,” ch. xii.

=============