=============

THE CHURCH TREASURY OF HISTORY, CUSTOM, FOLK-LORE, ETC.

________________

BY THE REV. GEO. S. TYACK, B. A.

TO the thoughtful man of to-day it must be almost inconceivable that so much controversy should ever have raged about the use of pictures in churches. At the present time there is scarcely even a nonconformist community that has not practically admitted the propriety of their use, although in some quarters an illogical, indeed an incomprehensible, distinction seems to have been drawn between transparent pictures in the windows, and paintings on the walls. The Puritans of past centuries were most narrow-minded in their condemnation of art, but they were also more consistent. To them apparently all art was a sacrament of the devil, whereby he entangled and ruined the souls of men. Milton, it is true, felt the hallowing influences of art, and in his Il Penseroso sings the praise of architecture, painting, and music —

“Let my due feet never fail

To walk the studious Cloisters’ pale,

And love the high embowered roof

With antique pillars mossy proof,

206

And storied windows richly dight

Casting a dim religious light;

There let the pealing organ blow

To the full-voiced quire below,

In service high and anthem clear,

As may with sweetness through mine ear

Dissolve me into ecstacies,

And bring all heaven before mine eyes.”

But these were the thoughts of the young Milton of twenty-five or six, the author of the Mask of Comus, and the entertainment Arcades; not of that man of sterner mould whom we meet in his later works.

It was natural that in the first centuries the Christians should exhibit great caution in the use of pictures. The Jews who had embraced the new faith clung for the most part tenaciously to the details of the older law, and to those traditions which their “eldars” had founded upon it, as is abundantly proved by many passages in the Acts of the Apostles and the Pauline Epistles. On the other hand the church would certainly realize that great care was needed in the treatment of converts from Paganism, accustomed to the worship of all manner of sculptured or painted idols, lest even pictures symbolical of the Christian faith should be abused rather then 207 used. That the primitive church was not, however, afraid to employ art as a handmaid, is proved by the Roman catacombs. The Catacomb of St. Priscilla, dates from Apostolic times, or at latest only just subsequently to them, the Catacomb of St. Callixtus is probably the next in age, and is not very much later; and in these, as well as in other sections of these sacred Christian cemeteries, pictures meet us on all hands. Simple studies of Our Lord as the good Shepherd, examples of the emblematic vine, and other subjects not beyond the talents of a poor and largely illiterate community, are some of the first specimens of Christian art. Representations of Old Testament scenes, more or less emblematic in treatment, and later of New Testament persons and events, followed.

There is evidence, it must be admitted, of a local suspicion of the use of pictures even in early times, for which there may have been special and local reasons. A council held at Elvira, in Spain, in the year 305, passed a canon declaring that “pictures ought not to be in churches, lest that which is worshipped and adored be painted upon the walls.” Yet in less than a century we have the description written by 208 St. Paulinus (who curiously enough had spent much time in Spain) of the elaborate pictures in his church at Nola in Italy. Scenes from Old Testament history adorned the walls, and in the apse was an emblematic design of the Holy Trinity, and another of the Cross. “In all its mystery,” says the saintly bishop, “shines forth the Trinity; Christ stands in the lamb, the Father’s voce thunders from Heaven, and as a dove flies forth the Holy Ghost.” The Cross was encircled with a crown of light, and the Apostles typified by a flock of doves. These pictures were in mosaic, as were many, if not most, of the early icons in the west, while those in the east are more commonly the work of the painter.

Amongst early writers of authority who refer to pictures in churches, we find St. Augustine of Hippo, who speaks of figures of St. Peter and St. Paul, of the martyrdom of St. Stephen, and the sacrifice of Abraham. Asterius, Bishop of Amasea, tells us that close to the spot where the relics of St. Euphemia, the martyr, were preserved, “the painter by means of his art, and to the best of his abilities, exactly portrayed on his canvas the martyr’s whole history, and hung 209 it in such a position as to be seen by all.” The purpose of these pictures is plainly set forth by a disciple of St. John Chrysostom, St. Nilus the Abbot, namely, “that they who cannot read the Holy Scriptures, may be able as they look upon the picture to call to mind the noble acts of those who have served God with sincerity,” and for this reason the same saint advised the prefect Olympiodorus “to full the holy temple on all sides with Scripture pictures by the hand of the most skilful artist.”

According to some authorities pictures were hung in very early times in the portico of the church, especially for the contemplation of penitents, who were not suffered to advance further into the sacred precincts. An example, which reminds one of this practice, exists at Lutterworth, where three figures are depicted in fresco above the northern door. The local tradition describes them as Queen Phillippa, King Edward III., and John of Gaunt, and avers that the Queen, countenanced by John, is requesting the King to confer the rectory of Lutterworth on John Wyclif. Another account describes the two males figures as those of Edward II. and Edward III. The style of the work is that of 210 the later fourteenth century, and the subject must be admitted to be very doubtful. A not uncommon design for the decoration of the wall over the north door was a figure of St. Christopher bearing the child Christ.

Encouraged by the church a great school of artists sprung up in Mediæval Europe, to whom we owe an incalculable debt of gratitude. The glorious works of the monastic painters, Fra Angelico, Fra Fillipo, and Fra Bartolomeo, of Michael Angelo and Leonardo da Vinci, of Duccio, Botticelli, Correggio, of Raphael, Giorgione, and a hundred more, were most of them produced for the decoration of churches or other ecclesiastical buildings. As illustrations it must suffice to quote the world-famed frescoes of Michael Angelo in the Sistine chapel at Rome, the glowing witnesses to the faith of Fra Angelico at Florence, and the Last Supper of Leonardo da Vinci in a convent at Milan, made familiar by means of countless copies. Many examples originally painted for the decoration of churches have found their way in modern times into museums and picture galleries in England or abroad, but every traveller in Europe, and especially in Italy and Spain is aware of the vast 211 amount of splendid art still to be seen in the cathedrals and monastic churches there.

Undoubtedly our own country, although producing no mediæval painter of mark, availed herself to the full of such opportunities as were afforded her, for the pictorial decoration of her churches. Very few old pictures remain to us, and not many traces or fragments even still exist, but there are enough to show that our forefathers appreciated and used this common-sense method of instruction, until the torrent of Genevan influence in the sixteenth century devastated the sacred art of the country.

The almost incredible suspicion with which all art was regarded by the continental reformers is illustrated by the correspondence of Christopher Hales with some of them. He had given orders for the portraits of six German Protestants to be painted and sent to him, but complains that one Master Gualter had “retained four of them. . . . because there is some danger lest a door shall hereafter be opened to idolatry.” He remonstrates in consequence with Gualter, and expresses himself as “greatly surprised” (as indeed he well might be) “that Burcher should persist in thinking that portraits can no wise be painted 212 with a safe conscience, and a due regard to godliness.” When such men as these, fanatical in ignorant scrupulosity, were allowed to advise the bishops and doctors of the English church, there is small wonder that an iconoclastic outbreak was the result. Hooper, in his “Declaration of Christ and His Office” (first published in 1547) admits indeed that “the art of graving and painting is the gift of God”; but he goes on to make the illogical distinction by which so great a means of religious instruction is specially excluded from the church, the home of religion. “To have the picture or image of any martyr or other,” he says, “so it be not put in the temple of God, nor otherwise abused, it may be suffered.” In the same spirit, Nowell, Dean of St. Paul’s, in a catechism published in 1570, while allowing that the second commandment in the Decalogue does not “wholly condemn the arts of painting and portraiture,” yet deduces from it the teaching “that it is very perilous to set any images or pictures in churches.” When ideas like these were rife, it will cause no surprise to find Hooper issuing, in 1551, injunctions to the clergy of the diocese of Gloucester, to the following effect: — “Item, that when any glass windows within any 213 of the churches shall from henceforth be repaired, or new made, that you do not permit to be painted or purtured (portrayed) therein the image of any saint; but if they will have anything painted, that it be either branches, flowers, or posies (mottoes) taken out of the holy scripture. And that ye cause to be defaced all such images as yet do remain painted upon any of the walls of your churches, and that from henceforth there be no more such.”

Then doubtless began the glorious era of whitewash, during which such figures and pictures as could not be taken away and destroyed were daubed over with lime. Thus in the accounts of St. Giles’s, Reading, for the year 1560, we find an entry, “For white liming the roode, 1d.”

Here and there, nevertheless, an ancient painting yet remains to us; some few have been recovered by the removal of the layers of whitewash under which they had been long concealed; and something has been done in recent years to supply the places of some that have been lost.

In the crypt of Canterbury Cathedral is a quaint painting representing the nativity of St. John the Baptist. St. Elizabeth lies on a couch with the infant Forerunner in her arms, while the 214 father, St. Zacharias, seated at a table, writes on a scroll his statement that the child’s name is John, to the evident astonishment of the assembled neighbours.

At Catfield, Norfolk, some very interesting frescoes have been preserved, by which the space above the arcade on both sides is adorned. The seven sacraments, the seven deadly sins and their appropriate punishments, and various other subjects are here depicted.

In the Galilee Chapel of Durham Cathedral are two figures, perhaps St. Cuthbert and St. Oswald, which have not been certainly identified. In cleaning the walls of the parish church of Crowle, Lincolnshire, at its restoration some ten years since, a mural painting was discovered; but unfortunately, before steps could be taken for its preservation, it crumbled away.

One subject, which apparently was formerly popular in England for the adornment of the space above the chancel arch, was the Last Judgment, known as a Doom.

One such exists in the Chapel of the Holy Cross at Stratford-on-Avon, having been discovered in 1804. The happiness of the blessed, and the tortures of the lost are represented with most 215 realistic force, but the effect produced on a modern spectator is scarcely the one aimed at by the artist. A better example is met with at Lutterworth. The Saviour Himself appears at the top seated in glory upon a rainbow, while two angels with trumpets summon the quick and the dead to meet Him. Beneath is the earth, represented as a brown expanse, on which a multitude of graves are seen, from which the dead are issuing — some as skeletons only, some as complete bodies. Two larger angels bearing scrolls are depicted, one on either side of the arch.

A Doom discovered at Wenhaston, Suffolk, in 1892, is especially noteworthy, both on account of the strange manner in which its existence was discovered, and for the intrinsic merits of the composition. It is painted upon an oak partition which fills up the arch above the chancel screen, and is said by competent judges to have been executed about the year 1480. At the Reformation the great crucifix, or rood, with the figures of St. Mary and St. John, which formerly stood against it, were taken down, and the painting was whitewashed, so that all trace, and in time all memory, of it disappeared. About 1860 a hole was cut through one side of this boarding to allow 216 of the passage of a stove-pipe, and, in 1892, the whole screen was pulled down as of no architectural or antiquarian interest, taken to pieces, and thrown into the churchyard, with a view to being entirely removed. By a piece of extraordinary good fortune the following night was exceedingly wet, and by the succeeding morning no small amount of whitewash had been swept from the boards by the pelting rain, and portions of the painting stood manifest to the astonished eyes of the workmen. It is needless to add that after this all the oak was carefully cleaned and replaced, the colours being wonderfully bright, and the whole forming one of the most interesting Dooms extant.

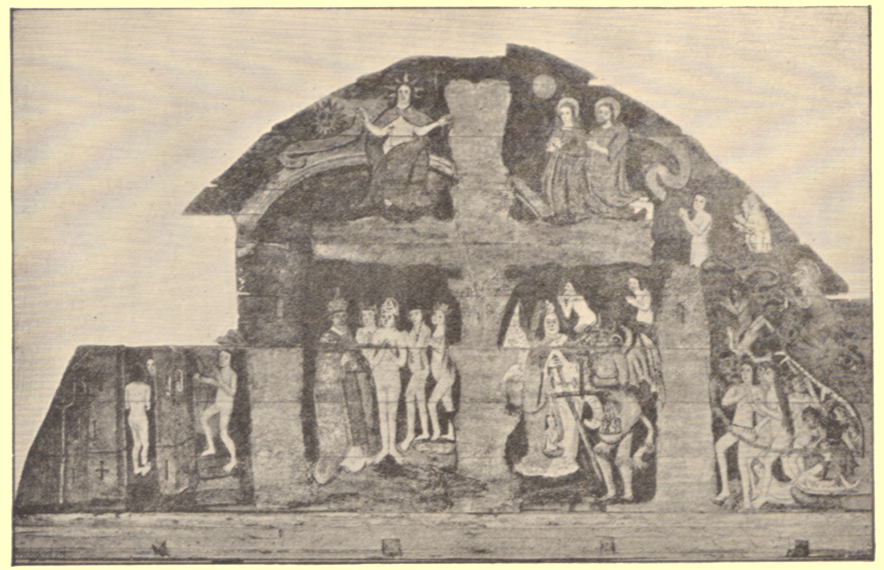

WENHASTON DOOM.

In the middle is a blank space, marking the portion originally covered by the rood; and similar reminders of the figures of St. Mary and St. John are on either side. Above the right arm of the cross is seated the Lord upon a rainbow, as in the Lutterworth Doom; while kneeling in supplication to Him on the left side are the Blessed Virgin and St. John Baptist, the latter identified by his “raiment of camel’s hair.” The rood with its attendant statues naturally divides the lower portion of the picture into four sections, and of this the artist has availed himself in arranging his

[217]

[218]

[blank]

219

subject. On the right side of the shaft of the cross is St. Peter, robed as a pope, receiving the souls of a king, a queen, a cardinal, and a bishop. Still further to the right is a castellated double gateway, at which angels are seen admitting the blessed. On the left-hand side of the rood we see St. Michael weighing souls, while the Devil, “the accuser of the brethren,” stands by with a scroll containing presumably his accusation against them. At the extreme left a huge head with gaping jaws, the usual mediæval method of suggesting hell-mouth, appears, into which the lost souls are dragged and pushed. At intervals, in the main design, bodies are seen rising from their graves. For clearness it ought perhaps to be added that the terms right and left are used above as in heraldry, for the opposite sides of the painting, not of the spectator. The portion of the oak which has been cut away contained the figure of an angel summoning the world to judgment, part of his arm and his trumpet being still visible. Several scrolls are inserted in the composition, the lettering of which has disappeared, but no doubt their inscriptions were of the usual kind in such pieces; “Come, ye blessed,” “Depart, ye cursed,” in the Latin of the Vulgate.

Another Doom, painted like this one on a panel, is preserved in the triforium of Gloucester Cathedral.

In the parish church of South Leigh is an elaborate scheme of pictorial decoration dating from the fifteenth century. The Doom occupies its usual place over the chancel arch, but spreads itself also over the nave walls. Over the arch we have the resurrection of the just and the unjust, who are summoned by angels robed respectively in white and in black, together with Hell-mouth and the usual accessories. Heaven is depicted on the north wall of the nave; a castellated gateway, at which stands St. Peter with his keys, gives admission to the celestial city, the towers and spires of which are seen in the distance. On the south wall of the nave we see St. Michael the Archangel engaged in weighing the souls, and the mystical figure of the “woman clothed with the sun,” and having the moon under her feet, is also introduced. On the east wall of the chancel another subject is treated, namely the Annunciation: on the south side of the window is a figure of the Blessed Virgin, standing with upturned eyes and holding a lily, while the divine Dove is seen descending upon her. It seems 221 probable that the effigy of St. Gabriel must at one time have stood on the opposite side, or at any rate that such was the intention. On the north wall of the aisle of the church is a painting of St. Clement of Rome, in full episcopal vestments, with an anchor, the emblem of his martyrdom by drowning. The picture of the Annunciation is the latest of these paintings, all of which were coated with whitewash, and some of them overlaid also with other paintings of a later date.

At the restoration of Blyth Church, near Retford, a Doom was discovered in the usual position and of the common type; every effort proved unfortunately fruitless towards preserving it when it was exposed to the air, but a photograph was taken of it before its final disappearance.

About fifteen years ago some quaint paintings were discovered on the south wall of the chancel in the little parish church of Easby, near Richmond, Yorkshire; the subjects being the appearance of the angels to the shepherds, the visit of the Magi, the taking down from the Cross, the entombment of our Lord, and the Resurrection.

222Above the arches of the organ-screen at Exeter Cathedral is a series of thirteen curious paintings of ancient date, representing some of the most striking scenes in scriptural history, such as the Creation, Paradise, the Deluge, Solomon’s Temple, and events in the life of our Lord, concluding with the descent of the Holy Ghost at Pentecost.

It will have been noticed that of all subjects the Doom was obviously the most common in England, and in considering the value of these paintings as instruments of popular instruction, it must be remembered that, in all the instances here quoted, and probably invariably, they stood in close connection with the Rood. The Wenhaston Doom is peculiar in having had the great crucifix actually fastened to it, but in the other cases the Rood undoubtedly stood on a screen beneath it. The whole arrangement would therefore form a singularly complete expression of the redemptive work of Christ.

In recent years steps have been taken in several places to revive the use of pictures in our churches. The mosaic enrichment of St. Paul’s Cathedral is a noble example, and when completed the work will add immensely to the beauty 223 of that splendid, but formerly rather dingy pile; the parish church of Darlington possesses a reredos or altar-piece, consisting of a picture in mosaic on a large scale.

It has often been maintained that our somewhat damp climate, and the smoky atmosphere of our towns, form almost insurmountable barriers to the use of frescoes in modern England; but experiment seems to have proved the contrary. To name one or two cases in which this form of mural decoration has been successfully employed, reference may be made to the designs by the late Mr. Gambier Parry in Ely Cathedral, and paintings in St. Andrew’s, Stoke Newington, St. John’s, Isle of Dogs, St. Peter’s, Bournemouth, St. Anne’s, Derby, and elsewhere.

At Womersley, near Doncaster, is a curious picture in tiles, recently inserted in the south wall, the subject being the institution of the Eucharist. It is of foreign origin.

One set of pictures commonly found in Roman Catholic churches, and with increasing frequency in English ones, is the Stations of the Cross. As a rule these fourteen incidents in the Passion of the Saviour are treated in a way that, as art, is contemptible. Some few specimens, are however 224 excellent; and when one remembers the dogmatic value of the facts set forth, and the pathos of the divine tragedy, one cannot but feel that art has here subjects worthy of its highest efforts. Antwerp Cathedral has a fine set of the Stations; and in England one of the best is at All Saint’s, Scarborough.

On the continent we expect, of course, to find many excellent examples of paintings in churches, besides those altar-pieces and pictures to which allusion has already been made. Time has told its tale upon many examples, as on Leonardo da Vinci’s “Last Supper,” and neglect and carelessness are found there as well as at home, but actual violence has not been offered to ecclesiastical art abroad to the same extent as was the case in England. Time would fail, therefore, to discuss in any detail the instances that may be met with in continental churches. The works of Mrs. Jameson, and of others, have familiarized us all with many of the most important of them.

It will not be out of place to mention here a rather striking form of decoration employed in some continental cathedrals on great festivals. This consists of the display of large pictures worked in tapestry. At Rouen they are stretched 226 around the columns in the nave, where besides their value as teachers, they add a useful warmth of colour to the place. At Brussels a similar custom prevails, but the tapestries, in this case framed, are hung between the pillars of the choir. In the choir at Aix, in Provence, are some tapestries stolen from St. Paul’s by the Puritans, and sold in 1656.

In conclusion, the words of a layman on the use of pictures in churches are well worth quoting. “I should like to be told why a man may not look at a picture in church. Nobody wishes to put doing so in the place of attending to the service, or of listening to the sermon, even though the pictures be more eloquent and instructive. Why may not a man attend to all if he likes? Objections can only be based upon what may be called the meeting-house theory about churches; the theory that a church is intended to be used at certain specified times, and for public worship and preaching only, which ended, the congregation are to be turned out, an the place locked up till next ‘service time.’ . . . The parish church should be not only the place of public worship, but also the place of private meditation and prayer. Every parishioner should 226 have free access to it at all reasonable times. Nay, it ought to be made interesting to attract him, and instructive to teach him when attracted.”*

Such is surely common-sense, and is one more plea for the acceptance of the position, surely also common-sense, that the employment of art in all its forms, and in the highest degree attainable, is not a mere luxury, not a simple question of ornament, but a necessary element in the education of our race.

===

Footnotes

* Modern Parish Churches, by J. T. Micklethwaite, F.S.A., Architect, King & Co., 1874.

=============