=============

THE CHURCH TREASURY OF HISTORY, CUSTOM, FOLK-LORE, ETC.

________________

BY THE REV. GEO. S. TYACK, B. A.

THE idea of pilgrimage, the making of journeys to spots consecrated by the lives and deaths of holy persons, seems to appeal to a sentiment common to the hearts of men. Herodotus tells us of an annual pilgrimage which took place in ancient Egypt. The Semitic races, with the exception of the Hebrews, journeyed yearly to Aphaca and to Hierapolis in Syria, in honour of Astarte; and the Jews by divine command thrice every year went up to Jerusalem to keep the great festivals of their faith. The practice exists at the present time more commonly among the Mohammedans and the Buddhists than elsewhere, the former congregating yearly at Mecca in numbers amounting to eighty thousand persons, and the latter at Kandy and Adam’s Peak, in Ceylon. The devotees of Brahminism also have their pilgrimages to Orissa.

Amongst Christian nations pilgrimages have been but seldom undertaken, at any rate on a large 146 scale, in modern times, although the alleged appearance of our Lady at Lourdes, and the miraculous cures affected there in consequence, have to some extent revived their popularity in some parts of Latin Christendom. Of the prominence given to these acts of devotion in Mediæval Europe it is scarcely needful to speak; two facts, which illustrate it, are known unto all men, namely that the pilgrimages to the Holy Sepulchre led to the epoch-making wars of the Crusades, and that those to the shrine of St. Thomas of Canterbury gave us our first great English poem.

Those, however, were only two out of many places which attracted pilgrims in the Middle Ages in greater or less numbers. The tomb of St. James at Compostella in Spain was one of the most famous shrines in Europe, next to which in popularity probably came that of St. Martin at Tours in France. Most countries had one or more spots well known as the resort of pilgrims. In Italy the tombs of St. Peer and St. Paul at Rome, and the Holy House at Loretto, attracted a crowd of travellers from all parts of the west. Switzerland saw them wending their way to Einsiedeln, Austria to Mariazell, France to St. Denis, and Scotland to St. Andrews. England 147 also had many celebrated shrines besides that of St. Thomas à Becket; and Westminster, Hereford, Peterborough, St. Alban’s, St. David’s and other cities were all visited by companies of pilgrims anxious to pay their devotions at the holy places which they contained.

We are at present concerned with the badges or signs which were to be bought at most of the chief resorts of pilgrims, and which the purchaser wore sewn on his cloak or in his hat, as a proof that he had fulfilled his vow, or performed his penance by the pilgrimage.

These signs consisted of plates or brooches, generally of lead or pewter, stamped with some design appropriate to the place of their origin. The pilgrim returning from Rome carried a little medal graven with the Cross-keys; he from Mount Sinai bore on his cloak the wheel of St. Catherine; but the man who had visited the holy places of Jerusalem placed in his hat, or bound to his staff, two small palm-branches, whence he was known as a palmer, while a cockle-shell denoted one who had been to Compostella.

Numbers of metal brooches bearing the effigies of popular Saints, and once used as pilgrims’ 148 signs have been found in various parts of Europe, and no doubt the sale of them formed at times no inconsiderable source of revenue to the churches containing the shrines. It would appear, in fact, that the clergy were protected by the civil authorities in the monopoly of their production. Leaden images of the Blessed Virgin were issued as signs of a complete pilgrimage to the Church of St. Mary Magdalene and St. Maximin, in Provence: and in 1354 a Royal ordinance was promulgated by the sovereigns of Sicily, Louis and Johanna, forbidding heir manufacture outside the convent. Another variety of the sign issued at this place has the figure of St. Mary Magdalene, accompanied by her traditional emblem, the box of precious ointment, kneeling at the Saviour’s feet. The arms of Anjou and Provence and a Latin inscription indicate the place of issue.

The cathedral of Amiens claims that to it was translated in 1206 the head of St. John Baptist. The relic was preserved on a great gold dish a foot in diameter, adorned with precious stones; and it speedily became an object of veneration throughout the surrounding districts. The pilgrim’s sign commemorating a visit to this 149 head, is a circular medal or brooch, on which is rudely depicted a priest bearing the head, while an acolyte with a taper stands on either side. Around the edge runs the legend: — “HIC EST SIGNUM FACIEI BEATI JOHANNIS BAPTISTE AMI” (this is the sign of the face of Blessed John Baptist of Amiens).

PILGRIMS’ SIGN, FROM THE CATHEDRAL OF AMIENS.

Other signs from places where relics of the same saint were said to have been preserved have been found. In one the face of St. John fills the whole medal, another (discovered at Canterbury) has a full-length figure holding the lamb, or Agnus Dei.

Among English saints none gained so much popular favour as St. Thomas of Canterbury, and several signs used by Canterbury pilgrims have come to light. One is in the form of an effigy of the Archbishop in episcopal vestments, and with the right hand raised in benediction, riding upon a horse. Another, somewhat similar, represents him carrying the processional cross, the mark of 150 his ecclesiastical dignity, while an attendant leads the horse. A sign of quite a different type consists simply of the bust of the martyr, episcopally vested with the name beneath.

For the benefit, no doubt, of poorer pilgrims, smaller and simpler devices were also adopted. We find little circular brooches merely stamped with a “T,” or with a head wearing a mitre, or a head distinguished by the emblem of St. Thomas, a sword. Another circular sign has again the head surrounded by the legend CAPUT THOME.

PILGRIMS’ SIGN FROM CANTERBURY.

Amongst these cheaper tokens is one with a pin behind for affixing it to the cap; this one is a small effigy of the Archbishop in full canonicals, bearing his crosier in the left hand, and raising the right in benediction. A more ornate specimen is oval, having the figure of St. Thomas seated, and holding his archiepiscopal cross. Pilgrims to Canterbury are said, not only 151 to have themselves worn badges such as these, but also to have put small bells on the harness of their horses. These had running as a legend round the rim, the words “CAMPANA THOME,” and no doubt they suggested the popular name of the flower known as the Canterbury bell.

It has been suggested that the signs which consist only of the head of St. Thomas are probably commemorations of a visit to that part of the Cathedral of Canterbury where the head alone had its shrine, separate from that in which lay the body.

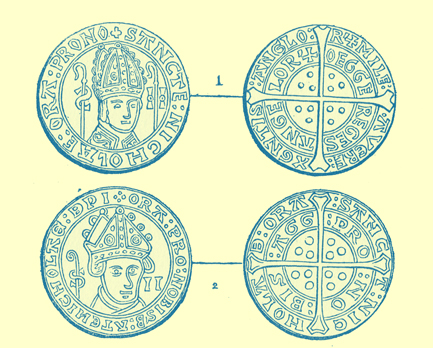

PILGRIMS’ SIGNS, FROM BURY ST. EDMUNDS.

St. Edmund, “king, virgin, and martyr,” was long one of the most popular of English saints. His relics were enshrined at Bury St. Edmund’s, 152 and his sign was a crowned head in an ornamental border. Another sign emanating from this abbey was made on the model of the silver pennies and groats of the time, and bore on the obverse the head of St. Nicholas, and on the reverse a cross with the opening words of a hymn to St. Edmund. The reputation of St. Edward the Confessor was more widely spread and more enduring. A sign not unlike a modern breastpin was sold to Westminster pilgrims, consisting of a king’s face, with a pin for fastening it. King Henry VI., whose unfortunate career, and mysterious death, stirred up on his behalf a share of public sympathy, gained for a short time a sort of pseudo-canonization at Windsor, and it was even asserted that miracles were wrought at his tomb. Pilgrimages accordingly took place thither, and an appropriate sign was struck, the figure of a king, crowned, and holding in either hand the orb and the sceptre, while a stag crouches at his feet.

The popular shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham issued figures of the Madonna and the Holy Child, or of small ampullae, or vases, stamped with a crowned W.

Other signs which may be mentioned are the 153 figure of a mitred abbot, and the name ST. LENNARD, probably from St. Leonard’s Priory, York; a royal head with the name KENELM, from the shire of St. Kenelm, king and martyr, at Winchcombe, Gloucestershire; a brooch with figures of St. Fiacre, his sister Syra, and St. Faro of Meaux, from the shrine of the first-named saint near Paris; St. Eloi working at his anvil, while a horse stands by, from Noyon. Signs have also been found of the three Kings of Cologne (a star), of St. Nicholas, of St. Laurence, of St. Olaf of Denmark, of our Lady of Bologne, and of St. Christopher, as well as others with a crucifix upon them.

Several signs have been found of doubtful origin, the one here engraved being an example. It is the full-length figure of a bishop, in full eucharistic vestments, standing in the act of benediction, while below is the word “Fordom.” Some have thought it a sign of St. Leonard, owing to the manacle on his right arm; others deem it a figure of John de Fordham, Bishop of Durham from 1382 to 1388, 154 and subsequently of Ely, where he was interred. Offerings are said to have been made at his tomb there. It is, however, suggested that fordom or “for-doom” may mean “false judgment,” and refer to something in the life of an unrecognized saint.

Pilgrimage to some of these shrines was rewarded with special privileges, and the pilgrims thereto were regarded with peculiar reverence, much as a Mohammedan whose green turban announces the accomplishment of the journey to Mecca, is regarded by his less fortunate fellows. There are stories of prisoners, during the times of the long wars between France and England, having been released on their captors noticing that they wore the pilgrims’ sign of Our Lady of Roc-Amadour, in Quercy. This was a medal having the Blessed Virgin enthroned on the obverse, and St. Amadour on the reverse. The shrine of St. James of Compostella, in Spain, was brought into special eminence by the fact that the Spaniards were forbidden to join in the Crusades, so long as they had not succeeded in fully exterminating the Moorish infidels from their own country; and in those circumstances a journey to Compostella was accounted an 155 equivalent to one to the Holy City. The shell, which formed the usual sign of this pilgrimage, was sometimes reproduced in metal, and occasionally had a figure of St. James upon it. The effigy of the Saint alone was also in use.

When so much honour accrued to the wearers of these badges, it is not surprising to find evidence that some people were not unwilling to gain the reputation of pilgrims without the danger and toil of the pilgrimage. We find, therefore, no less than three Popes, in three different centuries, namely, Alexander II. (1061-1073), Gregory IX. (1227-1241), and Clement V. (1305-1314), issuing bulls empowering the Archbishop of Compostella to excommunicate anyone who sold signs of St. James at other places than within the city.

The literature of the Middle Ages has many allusions to the use of these pilgrims’ signs. The supplement to the Canterbury Tales — which is but little later in date than the famous Tales themselves — tells us how, after venerating the holy relics shown to them, the pilgrims —

“Then, as manere and custom is, signes there they bought,

For men of contre should know whome they had sought.

Eche man set his silver in such thing as they liked,

And in the meen while the miller had y-piked

His bosom ful of signys of Canterbury brochis.”

In the Vision of Piers Ploughman, a pilgrim is described as having visited all the noted places of pilgrimage, and as wearing the marks which proved his wanderings. He had “seten on his hatte,” or on his cloak, the “Signes of Synay,” and “Shells of Galice,” the “Keyes of Rome.”

Giraldus Cambrensis tells us that after passing through Canterbury on his way to London, he wore the signs of St. Thomas hanging about his neck, and Erasmus, in a colloquy on “Pilgrimage for Religion’s Sake,” makes one of his characters ask — “But what kind of apparel is that which thou hast on? Thou art beset with semi-circular shells, art covered on every side with images of tin and lead.” To which the reply is, “I visited St. James of Compostella, and returning I visited the Virgin beyond the sea, who is very famous among the English.”

Louis XI., King of France, was greatly given to the wearing of these leaden signs, a fact to which, it will be recalled, Sir Walter Scott makes frequent allusion in “Quentin Durward.”

By a transition, natural enough to frail human nature, these signs, from being merely records of a meritorious act completed, came to be looked upon as charms, as if through them some part 157 of the blessing was continued to the wearer, which the pilgrimage was supposed originally to have procured.

As works of art these signs are for the most part as worthless as they are in intrinsic value, but as surviving relics of a custom now scarcely known in England, and as illustrations of such early writers as Chaucer and others, they are full of interest.

=============