=============

THE CHURCH TREASURY OF HISTORY, CUSTOM, FOLK-LORE, ETC.

________________

BY WILLIAM ANDREWS.

AT the commencement of the Queen’s reign, one of the sights of London was the wax-works at Westminster Abbey. In 1834, however, Madame Tussaud had established her famous exhibition, and the show at Westminster waned; with diminished receipts it was discontinued in 1839, after it had been for ages a source of considerable profit to the Abbey officials. For many years the effigies had been closed to the general public, and lost sight of; popular guides did not refer to them, and only by special order of the Dean could they be inspected. Dean Bradley, appreciating the antiquarian value of the figures, has thrown them open to sightseers once more, on payment of a small sum of money for admission to the Islip Chapel, where they are kept in glass cases.

In Saxon and Norman times, it was the practise when a monarch passed away to embalm the body, then dress it in costly regal robes, with a 276 crown on the head, and with much pomp carry it on a bier to its final resting-place.

From ancient chronicles may be gleaned interesting particulars of the stately funerals of mediæval times. Henry II. died in 1189, and his obsequies are described by an old chronicler. “He was cloathed,” it is recorded, “in Royal Robes, his Crown upon his Head, white gloves upon his Hands, Boots of Gold upon his Legs, gilt Spurs upon his Heels, a great ring upon his Finger, his Sceptre in his Hande, his Sworde by his side, and his Face uncovered an all bare.” Such is the brief but informing account of a royal funeral.

Prior to the interment of the body, it lay in state for a considerable time, and on either side of 277 it lighted tapers were placed, and attendants stood wearing hoods drawn over their heads. In the Middle Ages, burials were much longer deferred than they are in these later times. We may point out in proof of this statement, that the Black Prince died on June 8th, 1376, and that he was not interred until after Michaelmas of the same year. His widow died on August 7th, 1385, and it was not until the 7th of December following that letters were issued to the peers to attend her funeral.

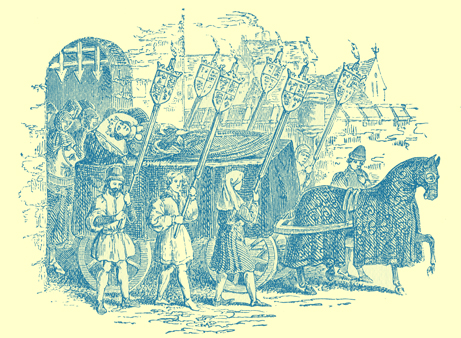

FUNERAL OF RICHARD II. (From an early MS. of Froissrt).

With the English era which followed the Norman rule, a change in the manner of conducting royal funerals was introduced. Lead coffins enclosed the body, and instead of exposing the corpse, a carved figure of wood, as natural in appearance as art could make it, dressed in the robes of the departed, was carried in the funeral procession, and deposited in the Abbey. In some instances, leather, plaster of Paris, and other materials were employed in making the effigies. Later, in the time of Elizabeth, and possibly a century earlier, the figures were modelled of wax, casts of the faces were taken, and with the aid of wigs, etc., almost life-like representations were made.

278A herse, or hearse, it is spelled both ways in old-time record, was used at funerals. We must not confuse it with the modern hearse. It was a temple-shaped structure of wood, richly-decorated with banners, hatchments bearing the arms of the deceased, draped and gilded, and no pains and expense were spared in beautifying it. A leading architect would design it.

HERSE OF JAMES I. (Designed by Inigo Jones).

Inigo Jones 279 planned the one for James I., and it is stated that he made the draperies of the statues that adorned it of white calico and starch, and the heads of plaster of Paris. This king’s funeral was conducted with much ceremony. Provision was made for placing lighted candles on the herse. When a funeral arrived at the Abbey, the wax effigy was deposited under the herse, and the coffin lowered into the grave. The herse remained for some time in the Abbey, depending greatly on the rank of the person to whose memory it was placed, or the requirements for space made by the death of others. Chaucer, in his “Dream,” refers to the practice of offering up prayers round the herse.

“And after that about the herse

Many oresons and verses

Without note full softly

Said were, and that full heartily,

That all the night, till it was day,

The people in the church can pray,

Unto the Holy Trinity,

On those soules to have pity.”

It was customary to pin short poems or epitaphs of a laudatory character on the herses. The best example that has come down to us is the epitaph by Ben Jonson on the countess of Pembroke: — 280

“Underneath this sable herse

Lies the subject of all verse,

Sidney’s sister, Pembroke’s mother.

Death! ere thou hast slain another,

Fair, and wise, and good as she,

Time shall throw a dart at thee.”

We read that on Bloody Mary’s herse were set up angels of wax, and the valence was fringed and adorned with escutcheons.

Mary, the queen of William II., died in 1694, and the last herse used in this country was the one under which her effigy was placed in Westminster Abbey. An interesting circumstance connected with her funeral may be mentioned: it was the first ever attended by both Houses of Parliament in state. The Lords appeared in their robes of scarlet and ermine, and the Commons in long black mantles.

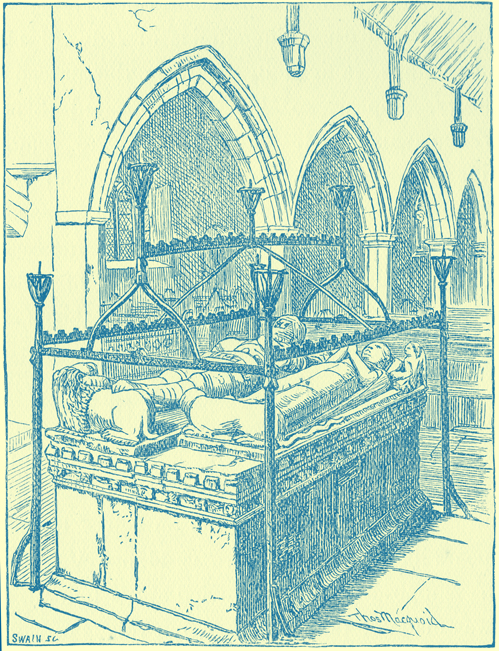

Drawings of herses made of wood are by no means rare, but not a single example of a herse of wood has come down to us, as far as we are able to discover. Some herses constructed of iron have survived the changes of three centuries. We give an illustration from the pencil of Thomas R. Macquoid of a good example over the tomb of Robert Marmion and his wife, in Tanfield Church, near Ripon. It will be observed 281 that it has sconces for holding seven candles.

HERSE AT THE MARMION TOMB, TANSFIELD.

There are only a few funeral effigies extant, but in the pages of history may be found many allusions to them. They can be traced back in Westminster Abbey to the fourteenth century. The earliest example of which we have been able 282 to find any account is that of Edward the First. Dryden, writing in 1658, names, in addition to Edward I., the figures of Henry V., Henry VII., James I., and their queens, also Prince Henry and Queen Elizabeth. The effigies of Edward III., and Phillipa, noticed by Stow in the preceding century, appear to have disappeared before Dryden’s day. It was customary to remove effigies when they were old and shabby, and when the space they filled was wanted for others. Dart, in his “Westmonasterium,” has some notes on the royal effigies. “ There are many of them,” says Dart, “sadly mangled, some with their faces broke, others broken in sunder, and most of them stripped of their robes, I suppose by the late rebels. I observe the ancientest have escaped best, I suppose by reason their cloaths were too old for booty. There is, I take it, Edward III. with a large robe, once of crimson velvet, but now appears like leather. There is Henry V., but I can’t suppose it is that carried at his funeral, for it was made of tann’d leather, but this is of wood, as are all the old ones. The later are of stuff, having the heads only of wood, as Queen Elizabeth, who is entirely stripped, and James I.”

Walpole was familiar with the figures, and 283 frequently visited the abbey with his friends to see hem. “You will smile,” he wrote in one of his letters, “when I tell you that t’other day a party went to Westminster Abbey, and among the rest saw the ragged regiment. They enquired the names of the figures, ‘I don’t know them,’ said the man, ‘but if Mr. Walpole were here he could tell you every one.’ ” The old and broken effigies are not exhibited, a few only of the more modern examples are on view.

The weird effigy of Queen Elizabeth attracts the chief attention. Here she is represented as she appeared in old age, but this is not the figure carried at her funeral. She died in 1603, and by 1708 the original effigy was worn out, and we learn from a chronicler of the period, that the only remains of her royal robes, which in the past has attracted so much admiration, was “a dirty old ruff.” The figure was restored by the Chapter in 1760, and the face is said to be a copy of that on her tomb. It is a small face, wrinkled about the chin and neck, but the features are delicate, the eyes expressive and bright. She appears arrogant, and an ill-tempered expression on the face renders it far from pleasing. The costume is interesting, and is an exact imitation of a part of the Queen’s 284 extensive wardrobe. The bodice is of ruby velvet, heavily embroidered with silver, long-waisted and pointed. It is low at the shoulders, displaying a scraggy neck. To accentuate the slimness of the tightly compressed waist, the hips are padded about a foot out on both sides. The petticoat is of the same colour and material as the bodice, but the over-skirt, cut away from the front, is of dark brown velvet. The petticoat is short, leaving exposed to view a neat ankle and small arch though broad foot in a dainty shoe with enormous bows. Elizabeth was vain of her feet, and had all dresses short in front to display them.

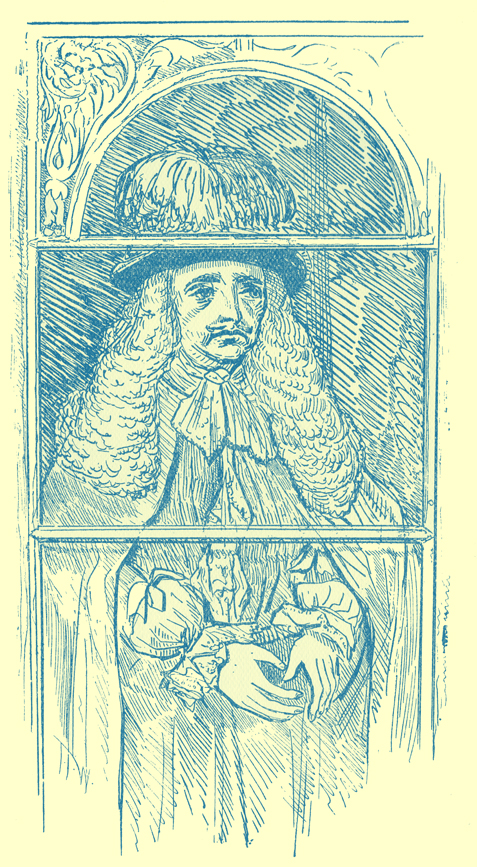

EFFIGY OF CHARLES II.

Charles II.’s effigy is the oldest of the original figures, now in a sufficient state of preservation to be on view, and is said to be a contemporary portrait modelled at the time of his death. It stood for two centuries above his grave in the south aisle of Henry VII.’s chapel, and was his only monument. When the king came to the throne the nation was full of rejoicing, pomp and magnificence prevailed, the people were mad with joy, and chroniclers confessed that they could not do justice when describing the glories of the festivities. This contrasts strangely with his funeral, for we are told by Evelyn, that “he was

[285]

[286]

[blank]

287

obscurely buried at night without any manner of pomp, and soon forgotten after all his vanity.” The “Merry Monarch” was a personable personage, and the wax figure represents him as a handsome man. His eyes are dark and mournful, and dark hair is flowing over his shoulders. The robes he wears are those of the order of the garter, and are of blue and red velvet, the ermine which edges them is of the dirtiest and dustiest description, and the beautiful and real point lace at his neck and wrists is perfectly brown with age. It must be conceded that the face is ghastly as are all the others, but it is a fine example of the art of modelling in wax, and gives a good idea of the true appearance of this pleasure-loving monarch.

Very interesting are the effigies of William and Mary, which are both in one case. William is a slight short man, whilst Mary is tall and imposing, and so the king is elevated on a footstool, but even then is not up to his wife in stature. His face is expressive, the eyes are hawk-like, the thin lips, the broad brow all bespeak the master soul within; his whole appearance seems to indicate the conquest of spirit over nature, for his frame is puny in the extreme. Mary is imposing yet not 288 striking in feature or figure. She wears a fine brocaded shirt, and a purple dress over it, and is laden with paste and imitation pearls, black with age.

Close by is Queen Anne sitting in a chair. Her figure is heavy and gigantic, and utterly devoid of grace. The face is full and pale, the eyes small and dark, and her dark hair hangs loose over her shoulders. Her dress is of rich yellow stain heavily embroidered, a state mantle falls round her, fastened on the shoulders by strings of large discoloured imitation pearls. A resplendent crown is on her head, in her hands are the sceptre and the orb, and round her neck the order of St. George. The face is from a cast taken after death.

Catherine, Duchess of Buckinghamshire, and her little son, the Marquis of Normanby, stand in a case together. The Duchess is dressed in the costume she wore at the coronation of George II. The petticoat is wondrously embroidered brocade of purple and yellow, and the skirt is of rich velvet sweeping far behind. In such a bad light is the effigy placed that the costly robes look dingier even than the others.

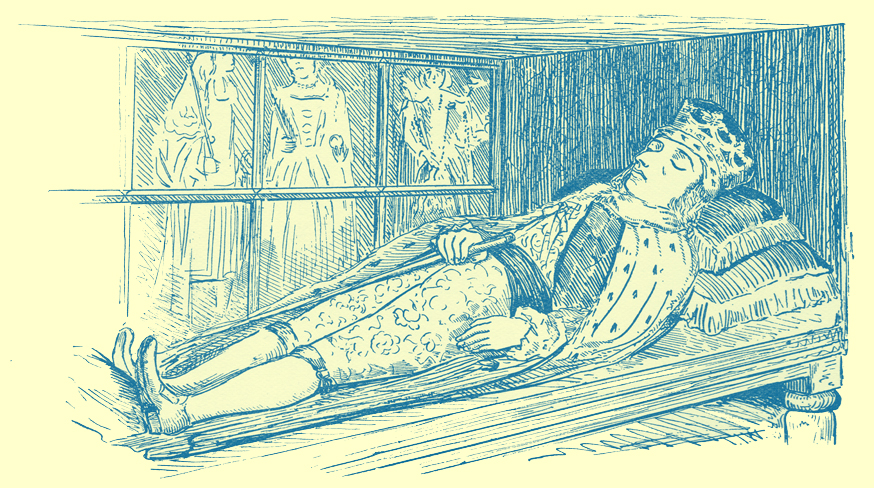

EFFIGY OF SHEFFIELD, DUKE OF BUCKINGHAMSHIRE.

In the centre of the chapel lies the effigy of the

[289]

[290]

[blank]

291

Duchess’s last surviving son, Edmund Sheffield, the last Duke of Buckinghamshire. At the early age of nineteen he died at Rome, and was brought to England for interment. The bereaved mother tried to induce the Duchess of Marlborough to allow the body to be taken to the abbey on the car that had been used for the great Duke of Marlborough, but the request was haughtily refused. The Duchess of Buckinghamshire boasted that an undertaker had promised to supply a much finer car for £20. This effigy, which is magnificently dressed, was the last ever carried at a funeral. A velvet cloak edged with ermine is thrown back, and displays a coat fastened down in front, and reaching to the knees, which is of most beautiful and costly texture. The ground is a delicate pink silk, but little of this is visible, so thickly is it embroidered with every imaginable shade of blending colours. This figure is laid at full length as though laid in state, and has a very impressive effect.

Frances, Duchess of Richmond, widow of the last of this noble line, the “La Belle Stuart” of Charles II.’s court, stands in the robes she wore at the coronation of Queen Anne. It is stated that she was the model for the figure of Britannia 292 on our coins, and judging from the effigy there is no reason to doubt the statement. The imperial pose of the small stately head is exactly the same as that with which we are all familiar. Her dress of richly embroidered brocade, and trimmed with exquisite lace is excessively beautiful. By her side is perched a parrot, said to be in memory of one which the Duchess possessed for over forty years, and which only survived her a few days.

The foregoing are all the effigies that are connected with the custom under consideration. The number of sightseers decreased when no fresh attractions were introduced in the form of new effigies, and something had to be done to increase the scanty incomes of the minor canons and lay vicars. The first figure set up was that of the great Pitt, the Earl of Chatham. A guide book published in 1783, after describing the funeral effigies, states, “what eclipses the brilliancy of those effigies is the figure of the great Earl of Chatham in his parliamentry robes, lately (1779) introduced at considerable expense. It so well represents the original that there is nothing wanting but real life, for it seems to speak as you approach it.” The pose is grand and dignified, in his hand is a folded document, and round his neck 293 is the order of St. George. It is a beautifully finished figure in every respect. When Chatham’s effigy was introduced the fee for seeing the waxworks was advanced from 3d. to 6d.

The last figure we have to notice is that of Lord Nelson, said to be modelled from a smaller one for which he sat. It is of considerable interest for the figure is attired in the clothes he wore with the exception of the coat. His waistcoat and breeches are of a white material, and his stockings are also white. The compilers of “The Deanery Guide to Westminster Abbey,” quoting from Notes and Queries, of Nov. 17, 1883, say: “There is convincing proof that the hat belonged to the Admiral, for when Maclise painted ‘The Death of Nelson’ he borrowed it to copy, and found the eye patch still attached to the inner lining, and the stamp, always found in old hats of that period, in the crown. The makers were obliged to put it in to show that the ‘hat tax’ had been paid. Nelson was blind in his left eye. On the left shoulder is a brass pin or nail, showing where the fatal bullet struck him. At his side hangs his sword, and numerous medals are on his breast.” In 1805 Nelson was buried at St. Paul’s, and his 294 grave was the chief attraction of London, crowds going to see it. The Abbey of Westminster was deserted, but when the Admiral’s effigy was set up, the novelty-loving people returned.

GENERAL MONK. (From “A Guide to the Wax-works of Westminster Abbey,” 1768).

After the death of Cromwell, General Monk, Duke of Albemarle, had much to do with bringing 295 Charles II. to the throne. His figure, clad in full armour, used to stand next to that of the king, but the battered remains now find a place in a corner. On his head used to be a cap which is now missing, and which the guide used to hand round; it is referred to in “The Ingoldsby Legends”: —

I thought on Naseby — Marston Moor — on Worcester’s

‘crowning fight;’

When on mine ear a sound there fell — it chilled me with

affright,

As thus in low, unearthly tones, I heard a voice begin

— ‘This here’s the Cap of Giniral Monk! — Sir! — please put

summut in!’

=============