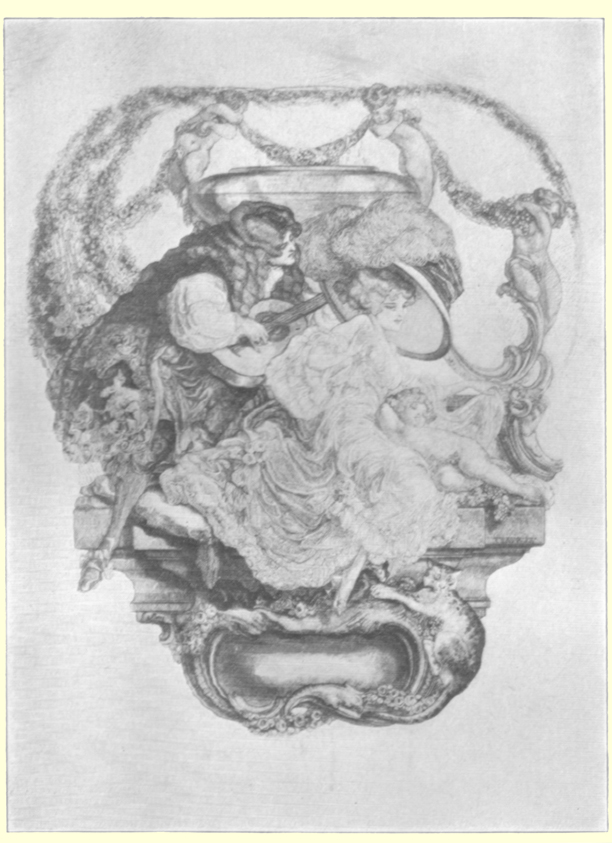

From The Works of Aretino, Translated into English from the original Italian, with a Critical and Biographical Essay by Samuel Putnam, Illustrations by The Marquis de Bayros in Two Volumes, Volume I., Chicago: Pascal Covici, 1926; pp. 55-76.

THE DIALOGUES OF NANNA AND ANTONIA, held in Rome under a fig tree, composed by the divine Aretino for his pet monkey, Capricio, and for the correcton of the three states os women. It has been given to the printer in this month of April, MDXXXIIII, in the illustrious city of Venice.

THE DIALOGUES

[I Ragionamenti]

of

PIETRO ARETINO

“The perverse and slightly theological mind

of my master, Pietro Aretino.”

from

The Very Pleasant Memoirs

of the

Marquis de Bradomin

Translator’s Note

Aretino’s DIALOGUES and his play, LA CORTIGIANA, are what Hutton calls “his terrible Medusa works.” In the RAGIONAMENTI, Aretino gives a vitriolic picture of the life of his time, a picture focusing on the life of women. After portraying the life of nuns, the life of married women and the life of courtezans, he comes to the bitterly satiric conclusion that the courtezan’s life is the best and most honorable one; and we hear his Antonia advising Nanna to make her daughter a prostitute. Read what Antonia has to say about “the best profession.” You will find there a surprisingly modern view of the subject, one which a Bernard Shaw might have had in mind when he wrote his “unpleasant”plays.

Obscene? Yes. But only as the life of the Cinquecento was obscene. Speaking of this, Aristide Raimondi in the introduction to his edition of the RAGIONAMENTI, says: “His men and women have but one obsession: Coitus. Beyond this, nothing. Absorbed in this, monks and nuns, women of every sort and men of every kind protract their lives in a crude solar reverberation which uncovers every nudity and ugliness. Surrounding this crown, the desert; and this is the manner in which Aretino interprets life.”

Nanna says it all when she declares: “The world is in ruins. Everything is going headlong. There is no faith, divine or earthly, no faith among the brides of Christ or those who are supposed to give faith to men; and I prefer my liberty. I am free, but I am loyal; I live with an open face. I sell openly my merchandise, while others pretend and simulate. Not I.”

Indeed, remarks Raimondi, Aretino “is a prostitute.” He has the prostitute’s instinct of social rebellion. “He throws mud not merely in the face of his contemporaries, but of a whole past. It would seem that he lifts up the world and places it against the 60 the light of the sun. . . . All is obscene and libidinous, everything is for sale, everything is false, nothing is sacred. He himself makes merchandise of sacred things to gain money and writes romantic lives of the saints. And then? Like Nanna, like Pippa, he finds it convenient to stand above men and holds them with the reins of their own vices. . . . The discipline which Nanna gives to Pippa is the discipline which guided the life of Aretino.”

The Italian critic concludes by remarking that: “Here is a lust, here is an obscenity, unbridled but profoundly human, warm and full, which ought to render these DIALOGUES preferable to the hypocrisy of so many most grammatic and stupid modern narrators. . . . We well may think that this is a book which should be read by many university professors of literature who have not read it. . . . It is not an insult to our times to reprint a work like the RAGIONAMENTI , for there is no work better worth reprinting today. . . . Such is this book; all impetus and vulgarity, poetry and sarcasm; and it ‘speaks as life speaks’ with its own cruel logic and contradictions. For this reason, the modern Italian literati do not read it.” Nor, it might be added, do the literati of any country.

It is interesting to note that the DIALOGUES were written at the same time as Aretino’s hypocritical and designing religious works. Perhaps, we may be permitted to imagine that they were in some manner an exhaust from that other uncongenial employment. Might not this account for the excess of devilish glee to be found in them? The DIALOGUES constituted, Hutton says, the Feuilletons of Aretino’s journalistic activity. They are vividly documentated, so vividly one is tempted to believe there is some truth in the story about Aretino’s having been himself a friar. In any event, these DIALOGUES, in addition to having been the models for the obscene works of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, are good reading and good pioneer realism.

THE LIFE OF NUNS

— and the benediction was in the vulgate.

Here begins the First Day of the Capricious Dialogues of Aretino, in which Nanna, in Rome, under a fig tree, recounts to her little Antonia the Life of Nuns.

THE NOVICE’S FEAST

If you had lovers before, what made a nun of you?

NANNA: Antonia, my dear, nuns, wives and wenches are like a way of the cross. As soon as you have mounted them, you stand a good bit thinking where you are going to put your foot; and it often happens that the demon drags your soul into the worst woe, as he did the blessed soul of my father that day, which made me a nun, although against the will of my mother of sainted memory, whom you may happen to know, or at any rate, what kind of woman she was.

ANTONIA: I knew her as in a dream, and I know (for I have heard tell) that she did miracles behind Benches, and I understand that your father, who was the sheriff’s mate, married her as the result of a love affair.

NANNA: Not to be reminded any more of my grief, how Rome was no longer Rome when widowed of so ripe a couple, and to come back home: it was on the first day of May that Mistress Marietta (for that was what my mother was called, although for fun she was commonly known as the beautiful Tina) and Sir Marbieraccio (for that was my father’s name), having assembled all our relations, uncles and grandfathers and cousins, male and female, with a flock of friends of both sexes, led me to the church of the monastery, dressed all in silk, girdled with ambergris, with a head-dress of gold, on which was the crown of virginity woven out of flowers, roses and violets, with my perfumed gloves and my velvet slippers; and although I remember by the calendar that it was only a short time ago I entered among 64 the converted ones, those were pearls that I wore on my neck and clothes that I had on my back.

ANTONIA: They couldn’t have been anything else.

NANNA: And so, all dressed up like a young lady, I entered the church, where there were already thousands and thousands of people, who all turned toward me as soon as I appeared, some saying what a fine bride Mr. God was going to have, while some said what a sin it was to make a nun out of so fine a girl, and others blessed me, and others ate me up with their eyes, and others said, “She’ll give some of the brothers a good year.” But I thought no malice in such words, and I heard certain very bestial sighs, the sound of which I knew well enough, which came from the breast of one of my lovers, who wept all the time the offices were being said.

ANTONIA: If you had lovers before, what made a nun of you?

NANNA: Some silly ones wouldn’t have had them, but they have no passion, anyway. And now, I was given a seat up above, among the other women, and after a little, they began singing the mass, and I, as was proper, was on my knees between my mother, Tina, and my aunt, Ciampolina, and a clerk was playing a laldettal on the organ; and after the mass, when my nun’s clothes, which were on the altar, had been blessed, the priest who had said the Epistle and the one who had said the Gospel raised me up and made me kneel again on the predella of the great altar. Then the one who had said the mass gave me the holy water, and after he had sung with the other priests the te deum laudamus and perhaps a hundred verses of the psalms, they divested me of my worldliness and clothed me in the spiritual habit, and the people, stepping on one another’s heels, made a noise like that in St. Peter’s or St. John’s, when some young woman, from madness, desperation or malice, lets herself be put behind walls, as I did once.

65ANTONIA: Yes, yes, I can see you, surrounded by that crowd.

NANNA: When the ceremonies were over, and the incense had been given me, with the benedicamus and the oremus and the allelua, a door opened, making the same creaking sound that the poor boxes do; and then, I was raised to my feet and led to the door, where twenty sisters with the Abbess were waiting for me, and as soon as I saw her, I made her a reverence, and she, kissing me on the forehead, said something, I don’t know what, to my father, to my mother and to my relatives, who were all crying as though their hearts would break, and no sooner did the door close than I heard an oimè that made everybody start.

ANTONIA: And where did the oimè come from?

NANNA: From my poor little lover, who the very next day became a wooden-shoe brother or a hermit in sackcloth, if the truth must be told.

ANTONIA: Poor wretch.

NANNA: And then, as the door closed, which was so quick that it did not even give me time to say good-by to my people, I thought for sure that I was being buried alive in a sepulcher, and I thought I saw dead women in the disciplines and ember weeks; and I no longer wept for my parents, but for myself. And I walked with my eyes fixed on the ground and my heart on what my fate was going to be, until we reached the refectory, where a crowd of sisters came running up to embrace me, and, calling me sister from the start, they made me raise my face a little, and when I saw some clear, fresh, rosy countenances, I was greatly encouraged, and looking about me with more security, I said to myself: Certainly, the devils can’t be so ugly as they are painted; and as I stood there, I saw a throng of priests and brothers, with a few seculars mixed in, all quite young, and the most polished and the most merry that I had 66 ever seen, and as each one took his friend by the hand, they looked like the angels that guide the celestial balls.

ANTONIA: Don’t put your mouth in the heavens.

NANNA: They looked like enamoured swains sporting with their nymphs.

ANTONIA: That’s a better comparison; go on.

NANNA: And taking them by the hands, they gave them the sweetest little kisses in the world and strove to see who could give the most honied ones.

ANTONIA: And who gave the most sugared ones, in your judgment?

NANNA: The brothers, undoubtedly.

ANTONIA: And for what reason?

NANNA: For the reason set forth in the legend of the whore of Venice.

ANTONIA: And then?

NANNA: And then, each one sat down at one of the nicest tables it seemed to me I had ever seen. In the handsomest place was my lady, the Abbess, with, at her left hand, Master Abbot; behind the Abbess was the Treasuress and, by her side, the Bachelor of Arts; opposite them sat the Sacristan and, beside her, the Master of Novices and a laymen and, so on, down to the foot, I don’t know how many clerks and as many again brothers. I was seated between the preacher and the confessor of the monastery; and then the victuals came on, and of such sort that, I must say, the Pope himself never had the like to eat. From the first onset, the morsels flew so fast that it appeared the law of Silence, written up where the fathers have their quarters, was being violated by everybody, for tongues and mouths both made the same murmur that silk worms do when they prolong their meal by devouring the leaves of those trees under that shadow of which that poor lad of a Pyramus and that poor lass of a Thisbe — may God 67 keep them company there, as he kept them company here — used to amuse themselves.

ANTONIA: The leaves of the white mulberry, you mean.

NANNA: Ha, ha, ha.

ANTONIA: What are you laughing at?

NANNA: I am laughing at the thought of a poltroon of a brother, God forgive me. I can see him, as, grinding away with two millstones and his cheeks puffed out like a trumpet-player, he puts his mouth to a flask and swills it down.

ANTONIA: May the Lord choke him.

NANNA: And then, beginning to get their fill, they commenced to chatter, and it seemed to me, in the middle of the meal, like being in the market place of Navona and hearing, on this side and that, the noise of buying and selling which this one and that one makes with this and that Jew; being satisfied now, they proceeded to divide up, each one taking another, until the seemed like swallows billing with swallows. I could not tell you the laughter that arose over the passing of a hind of capon, nor would it be possible to tell you the disputes which sprang up over everything.

ANTONIA: What baseness.

NANNA: I wanted to puke when I saw one sister chew of mouthful of food and convey it with her own mouth to that of her friend.

ANTONIA: The rascals.

NANNA: Then, perceiving that the pleasure of eating had been converted into that distaste which another feels when he has done a certain thing, they began imitating the Germans with their toasts: and the General, taking a great flowing beaker, invited the Abbess to do likewise and lifted it up like a false sacrament; and now, the eyes of all were glittering with too much beer, like the dolls that one sees in a show, and, veiled with wine, like breath on a diamond, they began to shut, and the 68 crowd, falling sleepily over the food, started making a bed of the table. Or would have done so if, up at the top of the board, had not come a fine lad with a basket in his hand, covered with one of the whitest and gauziest linen cloths that I can remember ever having seen. Was it snow? or frost? or milk? It surpassed in whiteness the moon in mid-month.

ANTONIA: What did he do with the basket, and what was in it?

NANNA: Wait a while. The lad, with a reverence to the Spaniardess from Naples, said: “Greetings to your ladyships;” and then, he added: “A servant of this fine brigade brings you the fruits of the earthly paradise.” And uncovering his gift, he placed it on the table, and at once, there was a clap like thunder, as the whole company burst into laughter, just as the little family which has seen the eyes of its father close forever bursts into weeping.

ANTONIA: Which is right and natural; see that you do the same.

NANNA: No sooner were the paradisical fruits visible than the hands of this one and that one began conversing with the thighs, breasts, cheeks and bagpipes of everybody else; and with the same distress with which rogues’ fingers converse with the pockets of dunces who allow their purses to be picked, they flung themselves on these fruits as does the crown on the candles which are flung down from the loggia on Wax-Chandleress’ Day.

ANTONIA: What were the fruits, tell me.

NANNA: They were those glass fruits which are made by Murano of Venice, in the likeness of a K, except that they have two little bells which would be an honor to any big cymbal.

ANTONIA: Ah, ha, now I have you by the beak; I’ve got you.

69NANNA: And she was not merely fortunate, but blessed, who came by the thickest and broadest one; and none could keep from kissing her own, as she remarked: “These overcome the temptations of the flesh.”

ANTONIA: May the devil not tramp out the seed.

NANNA: I, who played the modest country girl, stealing a few peeps at the fruit, was like a cunning cat which, with its eyes, watches the kitchen-maid and, with its claws, tries to get the meat which she, through carelessness, has left unguarded. And if it had not been that all the company about me had taken a couple and given me one, I, not to appear a weakling, would have taken my own. To make matters short, the Abbess, laughing and jesting, rose to her feet, and every one else did likewise; and the benediction, which she pronounced at table, was in the vulgate.

CONVENT SPORTS

Are these old bones going to sleep alone?

NANNA: We saw the cook had forgotten and left her door half-way open, and so we took a peek and saw her sporting with a Pilgrim, who, having come (I judge) to ask for alms to take him on his way to St. Jacob of Galicia, had gone inside to collect. His slave’s frock was spread out on top the cupboard, and his staff, on which was a tablet with a miracle, was leaning against the wall, and his wallet, filled with odds and ends, was giving great sport to a cat, to which the lovers, joyously occupied, paid no heed, while a cask, fallen upside down, was spilling wine over everything. We did not deign to lose any time in so sordid an affair as this but went on to the chink of my lady, the Butleress, who, having given up hope of her Parson’s coming, had fallen into such a fury that she was now tying a rope to a crossbeam and, leaping up on a trestle, she fastened the cord about her neck and ventured to kick the support from under her. And she had just opened her mouth to say to the Parson, “I forgive you,” when he came to the door, pushed it open and came in and, seeing the light of his life about to be snuffed out, threw himself on her, took her in his arms and said: “What things are these? And so, dear heart, you think I am a faithless one? And where is that divine prudence of yours? Where is it, I ask you?” At these sweet words, she lifted up her head as those who have fainted do when cold water is dashed in their faces, and she became herself again as frozen limbs do in the heat of a fire. 71 And the Parson, removing the rope and the trestle, placed her on the bed; and she, giving him a kiss, said slowly: “My prayers have been heard, and I want you to place a wax candle for me in front of the image of San Gimignano, with an inscription, saying, “She prayed to him and was freed’. ” And by saying this, she had the pious Parson well hooked on the prongs of her fork. Groping our way from these two, who did things out of duty, we came upon the mistress of novices in the act of drawing from under the bed a porter filthier than a mountain of rags; and she said to him, “Come out, my Trojan Hector, my bedroom Orlando, listen to your humble servant, and forgive me for the inconvenience I have caused you, for I had to do it” . . . And the big rascal, raising his breech-straps, replied with a sign from his member, which she, having no manual at hand to decipher his code, proceeded to interpret according to her fancy; and then the big clown, setting about to hunt the hare in the hedge, made her see a thousand glow-worms and bit her lips with his wolf’s teeth so charmingly that the tears came to her eyes; whereupon we, not caring to see the strawberry going into the bear’s mouth, went away.

ANTONIA: Where did you go?

NANNA: To a crack, where we saw a sister who appeared to be the mother of the discipline, the aunt of the Bible and the mother-in-law of the Old Testament, so far as I could get a good look at her. On her head, she had twenty hairs, like those on a bald wench, all of them full of nits, and perhaps a hundred wrinkles in her forehead; her eyebrow were thick and gray, and her eyes were oozing some yellow stuff.

ANTONIA: You must have had good sight, if you could see even the nits from so far away as that.

NANNA: Wait for me. She was slobbering, and her mouth and nose were snotty, and her jaws were like a bony 72 comb with two lousy teeth. Her lips were dry and her chin sharp, like the head of a Genoese. From her chin, for ornament, a few hairs sprouted out, like those of a lion, but prickly, I thought, as thorns. Her breasts were like the purse of a man who has no grain and were attached to her bosom by two cords. Her body (mercy on us) all scrupulous, was drawn backward and bent forward. And it’s the truth I’m telling you, she had around her a garland of cabbage leaves which looked as though they had stood for a month on the head of a scurvy wretch.

ANTONIA: Just as Saint Nofrio wore a pothouse stave around his shame.

NANNA: So much the better. Her thighs were straws covered with dried parchment, and her knees trembled so that it was all she could do to keep from falling every time she walked. I will leave you to imagine her ankles, her arms, her feet. And I’m telling you, the claws on her hands were as long as the one Roffiano had on his little finger, but hers were full of malice and manure. Them, bending over the earth with a coal, she drew stars, moons, squares, circles, letters and a thousand other thingmajigs; and all the time she was doing this, she kept calling the demons by a hundred names which the devils themselves would not be able to remember. The, whirling around three times about these contraptions which she had drawn, she leaped sky-high, muttering all the time to herself. Then she took a figure of fresh wax into which a hundred needles had been stuck (if you have ever seen the mandrake, you know what it looked like), and placing this as near the fire as she could stand, she turned it over and over, as gardeners and fig-eaters do, in such a way that it would cook and not burn. And she kept repeating these words:

Fire burn, fire waste

The cruel one who flees in haste.

And whirling it around with more fury than would support a lunatic asylum, she went on:

May this great itching that I feel

Move my god of love to kneel.

And as the image began to get very hot, she muttered, with her face fixed on the ground:

May the Demon be my joy,

Come or die, my pretty boy.

At the end of these verses, some one came beating on the door, out of breath, like one whose feet (when he has done damage in the kitchen) have saved him from a mountain of blows on the back. Then she, putting away quickly the instruments of incantation, opened the door.

ANTONIA: Naked as she was?

NANNA: Naked as she was, and the poor man, exhausted by her necromancy, as if he was famished with hunger, threw his arms around her neck and kissed her, with as much zest as if she had been the Rose and the Rainbow, and praised her beauty, as those do who make sonnets to their Tullias. And the cursed phantom, shaking all over and leaping for joy, said to him, “Are these old bones going to sleep alone?”

STORY OF A BITCH

Which commences with a laugh and ends in weeping.

We heard a brother, a most excellent brigand and a big greasy fellow, telling a fable to I don’t know how many sisters and priests and seculars, who, having played at dice and cards all night and ended by becoming tipsy, had come in to gossip and jest with the friar, who was telling them a story, which I am going to tell you, a story which commences with a laugh and ends in weeping, all on account of a big stallion of a hound. Having got an audience, the friar began:

Two days ago, as I was passing through the square, I stopped to watch a little bitch in heat, with two dozen whelps at her heels, attracted by the odor of her droppings, which were as round and rosy as burnt coral. They ran along smelling her all the way, now this one and now that one, and this silly sight had collected a great troop of lads, who were watching her as she would leap, now over this one, dropping a couple of handfuls, and now over this other, dropping a couple more. I, at the sight of such sport as this, had just put on a proper friar’s face, when there suddenly appeared on the scene a dog from a hayrick who seemed to be the lieutenant of all the butchers in the world, and seizing one of the other dogs, he threw him to the earth, furiously, and then, leaving him, downed another, nor did he leave a whole skin on their backs. At this, some of them flew this way and some that, and the big dog, arching up his back, ruffling his hair as a pig does its bristles, squinting his eyes, gnashing his teeth, snarling and foaming at the mouth, stood looking at the unlucky little bitch. After sniffing the pretty thing for a moment, he gave her two shoves which made her howl like 75 a big dog, but she slipped out from under him and ran away. And the whelps, which had been standing guard, taking after her, the big one followed in a rage. The little once, spying a crack in a closed door, suddenly leaped inside, and the whelps with her. Whereupon, the poltroon of a hound squatted down outside, for the truth is, he was so stupid he did not see where the others had gone, and so, he stayed there, biting at the door, pawing the earth and howling like a lion with the fever. After he had been there a good bit, one of the poor things came out, and the treacherous hound, seizing it, took off an ear, and when a second one appeared, he did worse to it. One by one, he punished them as they came forth and made them clear the country as villains clear at the coming of the soldiery. Finally, the young bitch came out, and seizing her by the windpipe, he fixed his teeth in her throat, while the lads and the people who had gathered for this dog festival were sent scattering, and cries went up to heaven.

Here ends the First Day

of the

Capricious Dialogues of Aretino.