[Click on the footnote symbols and you will jump to the note on the bottom on the page. Then click on the symbol there and you will be magically transported back to where you were in the text.]

From Romantic Castles and Palaces, As Seen and Described by Famous Writers, edited and translated by Esther Singleton; New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1901; pp. 99-104.

[99]

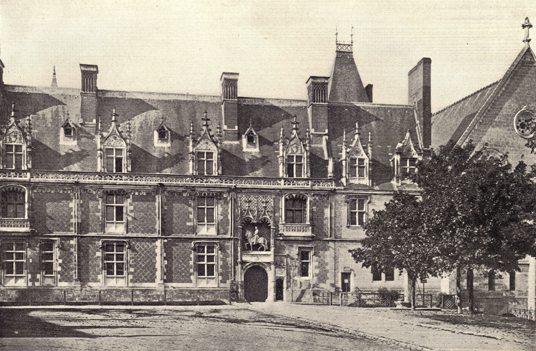

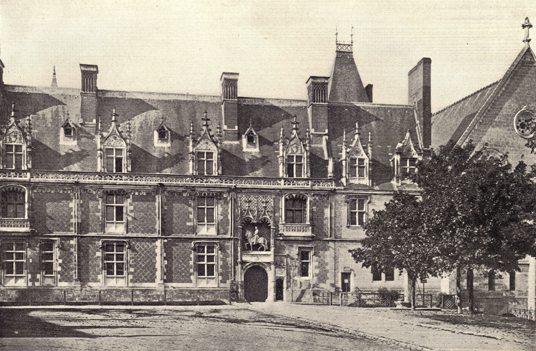

CHATEAU DE BLOIS, FRANCE.

THE castle of Blois would be without a rival in France if Fontainebleau did not exist. The first time we enter that interior court, the four sides of which each tell the history of a great period of architecture, we are dazzled by the throng of memories and ideas that start from these four great pages. The obedient stone, in accordance with the epoch, has recorded the suspicious precautions, the paternal confidence, the chivalric enthusiasm and the majestic isolation of the masters of this royal dwelling. Pure feudalism is written in the mighty walls of the fortress of the Counts of Blois. The transitional style, one of the most important examples of which is offered by this castle of Louis XII., marks the change from the feudal system to the unitary monarch prepared by Louis XI. This youthful monarchy, already absolute though tempered by the great aristocratic individualities, already glitters and triumphs in this brilliant façade built by the young victor of Marignan. By the side of this splendid façade, like a severe master beside a turbulent pupil, the severe profile of the castle, built by Mansart, suggest the absolute and uncounterpoised monarchy of Louis XVI., — unity without diversity, force without grace.

Thus the unknown architect who cut the walls of the 100 mighty fortress out of the rock for Thibault le Tricheur; and the artists, native in all probability and therefore unknown, who drew the arabesques of Francis the First’s stairway; and Joconde, the architect of Louis XII.; and Mansart, the architect of Gaston of Orleans; and all those bold stone-workers, unknown to themselves, doubtless, in those four façades have shown the four chief phases of royal authority. “Monuments are the true writings of the nations.”

Above the city of Blois, upon a triangular plateau, whence the view embraces the vast panorama of the left bank of the Loire, formerly stood a fortress, the origin of which is lost in the obscurity of ages. It was one of those redoubtable holds in which the great feudal barons watched for their prey and kept what they captured. It was one of the most formidable of all, and it is stated that it was never reduced, nor even besieged. Three narrow ascents, shadowed on either side by high walls, gave access to it. A double ring of fortifications was in front of the donjon, which, in case of siege, was the last resort of the master of this formidable abode. The first enclosure, called the lower court, or fore-court, to-day forms a courtyard of considerable size, at the end of which rises the front built by Louis XII. Ruined towers with thick walls still testify of the precautions taken to defend this first circuit.

Immense offices, a church the foundation of which dates back from the Eleventh Century, and which must not be confounded with the chapel that is to be seen in the present castle-yard, and lodgings for the canons and servants of 101 this church formed a vast circle of buildings around this first courtyard where also were to be seen the habitations of the count’s principal officers. There, in succession, afterwards arose the house from the window of which Georges d’Amboise, counsellor to Louis XII.,* conversed with his master; the house of the Duc d’Epernon, who favoured the flight of Marie de’ Medicis; and that other mansion where, on June 13th, 1626, Louis XIII. caused the arrest of the Prince de Vendôme, accused of being concerned in the Chalais conspiracy.

The castle built by Louis XII. now stands on the spot where the second enclosure began. Access to the latter was gained by a drawbridge thrown across a moat between two strong towers. Close to this bridge was a narrow passage communicating with the covered way called the Vault of the Castle, which has lately disappeared and which lead to the Place des Jesuites. It would be rash to pretend exactly to reconstruct the physiognomy which this second enclosure presented in the Twelfth or Thirteenth Century. The buildings of the background, vast edifices raised by the Counts of Blois, of the house of Châtillon, have completely disappeared and are only visible to-day in the drawings of de Cerceau. It is on the site of these buildings that Gaston d’Orléans raised, about 1635, the cold and regular building that bears his name.

It was between the thick walls of this hall and the no less thick walls of the Tour des Moulins that Francis the First wedged his château in. If we leave the Hall of the Estates, deferring till a little later a visit to the elegant edifice 102 of that prince, and go immediately to the tower that terminates it and connects the château of Francis the First with that of Gaston of Orleans, we shall have traversed all that now remains standing of the ancient strong castle of the Counts of Blois.

The château built by Francis the First, by the abundance and variety of its ornamentation, crushes the simple abode of Louis XII. Beside this strong and severe building it produces the effect of a young bride covered with laces beside the rich but serious and durable robe of her grandmother.

It was Louis XII., however, who laid the foundations of Francis the First’s wing. But these foundations had scarcely risen above the ground when he died. The plan adopted at that time only required one façade, — that of the courtyard. Francis the First had another building joined to the original one. When the addition was made, the strong partition-wall that terminated the first building and to-day separates the two sides of the edifice was already far advanced, so that it was necessary to pierce it with doorways that now allow us to appreciate its thickness. We are told that three years sufficed for the young victor of Marignan to carry this enterprise to the point at which we see it to-day. The king’s plan was to add two other wings to the castle that would thus have formed a perfect square. But Francis the First lacked the money necessary for the execution of this colossal plan, as Louis XIV. did afterwards for Versailles. The Field of the Cloth of Gold and the Italian war had exhausted his resources. During the 103 years that followed, the many catastrophes that overwhelmed France — the loss of Milan, the death of Bayard, the battle of Pavia, and finally the activity in Madrid, — destroyed Francis’s passion for building, — that love of the square and trowel that was common to him and all the great sovereigns of our country. When he returned from captivity, in 1526, with his head full of fairy-like Arab and Moorish constructions, he was already dreaming of Chambord, and neglected Blois, in which, however, had been gathered the money for his ransom. The grand project, conceived in 1516, was therefore abandoned, and the unfinished castle of Blois remained as we see it to-day, — a curious and incoherent assemblage of monuments of divers styles and periods.

We have heard nothing about the château built by Gaston of Orleans, not that that edifice is without merit, but its cold regularity disagreeably contrasts with the Renaissance architecture, so sparkling and prodigal and full of caprice. It was for the purpose of completing that correct and wearisome monument that Gaston wasted to destroy what remains of Francis the First’s wing. He would gladly have said, like Louis XIV.: “Remove those grotesque piles.” For it is a singular fact that at that time good taste joined in the same condemnation the Middles Ages, whose wonders were considered barbarous, and the Renaissance which had led the arts back to the purer forms of antiquity. With bare stones and straight lines throughout, yet there was something of the majestic gravity of Louis XIV. in the work of his uncle Gaston. 104 In order that the straight line may produce great effects it must be developed over the immense surface of a Louvre or a Versailles. At Blois it is only insignificant. This château would serve for anything, — a museum, a library, or a tribunal, just as well as the abode of a prince. They were going to pull down what they called the shanties of Louis XII. and substitute a fine iron grille for them. Francis the First’s wing found grace in the eyes of the destroyers on condition of sheltering the household: the kitchens had to be placed somewhere! It is true that this happened in 1823, only a few years after the Empire.

The work of a period of transition, when tranquillity was succeeding agitation, this palace of the chief of the Fronde does not possess the same power and self-confidence that came afterwards, but we already feel something in it of the imposing unity and the majestic ennui of the great reign.

Elf.Ed. Notes

* Read a joke that made its way to America, about the Cardinal, Georges d’Amboise in anecdote in The Repository of Wit and Humor; comprising more than One Thousand Anecdotes, Odd Scraps, Off-Hand Hits, and Humorous Sketches; selected and arranged by M. Lafayette Byrn, M. D., on this site.